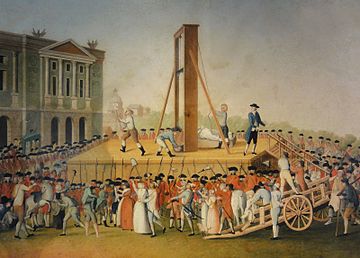

It seems like a cruel and unintended foreshadowing of a historic event, the way an extravagant necklace served as the last straw in bringing a glamorous queen’s neck to the guillotine.

This story is about the infamous and ultra-ostentatious necklace from 18th-century France. It was studded with diamonds and cloaked in deception.

The sequence of events seems like a tall tale of ambition, betrayal, and failed attempts at redemption woven by fiction writers.

You may even question its plausibility, but it’s a true story that contributed to the downfall of Queen Marie Antoinette and King Louis XV.

A little context: The public was becoming increasingly disillusioned with the monarchy.

They were bitter about the absurd privileges afforded to nobility and the clergy. They also looked down on the extravagance in the palace, excessive spending on wars, and high taxes slapped on the ordinary citizens.

A revolution was simmering, and a shining necklace added to the heat that led to the monarchy’s overthrow and the rise of the republic.

An Elaborate Scam

The grand scam all began with one ambitious woman. An illegitimate descendant of the royal house of Valois, adventuress Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy, self-styled as Comtesse de la Motte, found an opportunity to elevate her social and financial status by means of conning the elite.

She was married to Nicolas de la Motte, an officer from the gendarmes. She also took a lover: Rétaux de Villette, a soldier and a forger.

Together, they planned and executed an elaborate ploy to scam a rich and notable man named Cardinal de Rohan, former ambassador of France to Vienna.

This scam had a far-reaching impact, with nothing less than royalty suffering its consequences.

A Dangerous Liaison, A Desperate Attempt

The Comtesse associated with Cardinal de Rohan and, according to some accounts, eventually became his mistress.

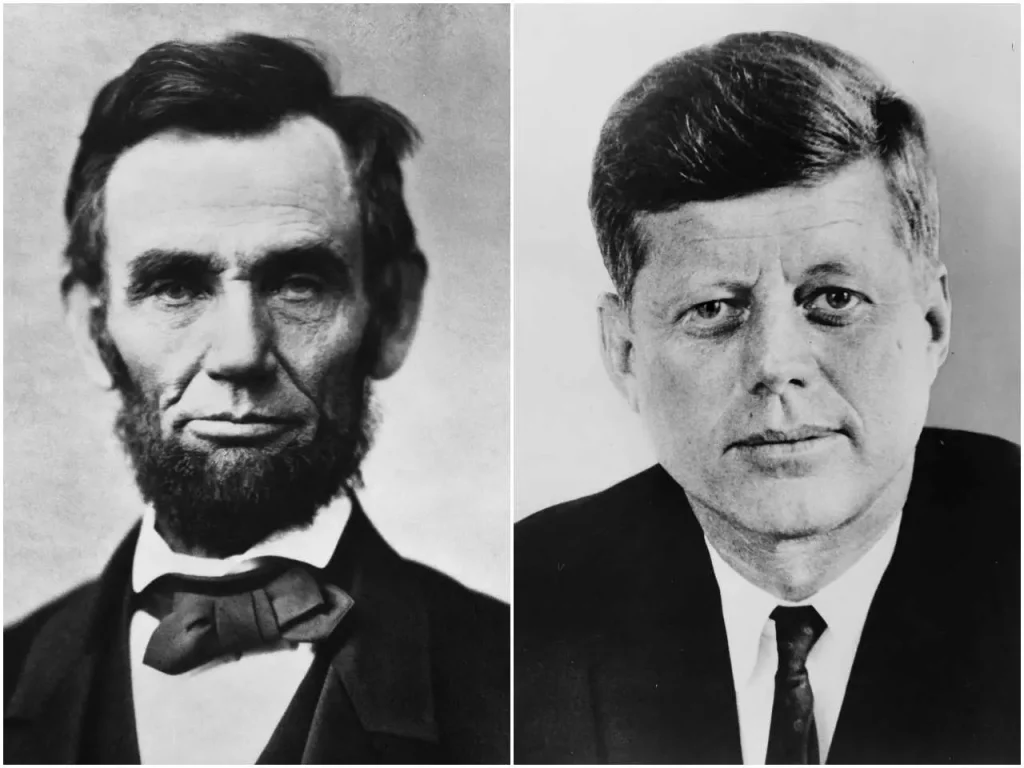

The Cardinal, by way of his family heritage and disreputable ways, was disapproved of by Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, the Queen’s mother. And Marie Antoinette, influenced by her mother’s opinion, shared the same disdain for Rohan.

Aware that he had fallen off the royals’ graces, Rohan was desperate to regain their approval and maintain access to greater social and political influence.

Learning about this, the Comtesse de la Motte came up with an idea. A luxurious necklace, waiting to be bought, would play a major role in this epic ploy.

A Lavish Jewel with No Takers

This luxurious necklace worth around 2,000,000 livres (roughly $15 million today) was created by jewelers Charles Auguste Boehmer and Paul Bassange.

It was designed and meant to be sold to King Henry the XV for his favorite mistress, Madame Du Barry.

Unfortunately, the king died of smallpox before an offer was made, and Marie Antoinette exiled the supposed recipient after her husband’s succession to the throne.

The jewelers tried to offer it to Marie Antoinette. Despite being known for her extravagant fashion, she refused the necklace with its 647 shimmering jewels and 2,800 carats, saying, “France has more need of seventy-fours [ships] than of necklaces.”

Rightly so, as it would have been perceived as an insult to the masses for the queen to wear it amidst France’s worsening economy.

Trickery that Tarnished the Royal Reputation

Marie Antoinette didn’t exactly have a sterling reputation among her subjects, and the trickery involving this necklace led to the further erosion of her already damaged reputation.

Given France’s financial woes, the Queen’s excessive spending, lavish lifestyle, and seeming indifference to the plight of the masses made her vastly unpopular.

Unknown to her, the necklace she refused is to become an instrument to her dark end. The Comtesse de la Motte tricked Cardinal Rohan into believing she had connections with the palace and could help him get into the Queen’s good graces.

Through fake letters that were supposedly from the Queen herself and an impostor the Comtesse hired, a prostitute named Nicole d’Oliva, who resembled the Queen, the con artist put her scheme into motion.

She set up a meeting between the Cardinal and the impostor late at night on August 10, 1784, at the Grove of Venus in the gardens of Versailles. Believing it was Marie Antoinette, the Cardinal was convinced he was on his way to gaining the Queen’s goodwill.

Rohan was conned to support the Queen’s charities, but his money only went to the Comtesse’s purse. Eventually, the Comtesse made him believe the “Queen’s letter” requesting the Cardinal to buy a certain necklace she greatly desired to wear during the Candlemas.

Motivated by his desire to be part of the royal inner circle, Rohan agreed and fell victim to the Comtesse’s scheme.

Multiple Victims

Of course, the jewelers were more than happy to sell the expensive necklace to the Queen via the Cardinal. After some negotiation, the piece was sold at a discounted price of 1.6 million livres over four periodic payments.

The necklace was then delivered to the Cardinal’s estate. Through the Comtesses’ orchestration, Vilette, posing as the queen’s courier, took the necklace to the palace. She broke it down to its diamond pieces and her husband slash partner-in-crime Nicolas de la Motte sold them piecemeal in London. The tricksters succeeded with their heist, but they would pay the price later on.

Noticing that the Queen hadn’t worn the necklace at Candlemas and other social events, the Cardinal and the jewelers became increasingly concerned. They were unaware that the necklace had never been delivered to the Queen. Consequently, no payment was made to the jewelers.

The jewelers sent a letter to the Queen to inquire if the necklace was to her satisfaction. Clueless and annoyed about something she had no idea about, the Queen discarded the letter.

Impudence, Investigation, Infamy

The jeweler then went to personally meet with the Queen’s lady’s maid, Madame Campan, to seek clarification and redress for the necklace. She asked for more details about the transaction, and the Cardinal’s name was mentioned.

Soon enough, details about the letters supposedly signed by the Queen herself requesting the Cardinal to buy the necklace on her behalf began to surface.

The Queen reiterated her ignorance of the whole thing. The King, already wary about scandals that would place the Queen in a bad light, summoned the Cardinal for an investigation.

Rohan explained himself and learned that the Queen made no such request and wrote no letters about the necklace. Signing “Marie Antoinette de France” was never her practice, a fact that the Cardinal should have known.

Goodwill Gone Wrong

It dawned on Rohan that the Comtesse tricked him. He pointed to her as the schemer and said he merely wanted to gain the Queen’s regard—he did not mean any harm. The King, greatly disappointed and outraged at how a highly educated and pedigreed Cardinal fell victim to a con artist, suspected that he may have been complicit in the scam.

The King sent the Cardinal to the Bastille despite his minister and Keeper of the Seals, Armand de Miromesnil, advising against it. In the minister’s opinion, detaining the Cardinal could be perceived as an abuse of royal power, which was the last thing they needed at that time of social and political upheaval.

Bastille was synonymous with torture executed by the Ancien Regime and painted a picture in the public’s mind that the godly Cardinal was being mistreated. In fact, he was kept outside the prison towers in a furnished apartment.

The parties involved were investigated and arrested: the Comtesse, her wife, her lover, and the occultist Count Cagliostro, a client of the Cardinal, on whom the Comtesse pinned the blame as the schemer. The Comtesse was arrested as she was in the middle of a spending spree, buying numerous lands in France.

In an attempt to clear the Queen’s name, a public trial took place. However, this backfired as the public sympathized with the Comtesse.

As details of the case became public knowledge, malicious rumors spread that the Queen had a sexual liaison with the Cardinal. This was untrue, but to those who already had a negative view of Marie Antoinette, it fueled the fire of their growing anger.

A Brilliant Jewel That Led to a Queen’s Dark Ending

The Cardinal and Cagliostro were tried at Parlement de Paris on May 31, 1786, followed by the others not long after. The Cardinal was acquitted but had to seek the King’s pardon for his “meeting” with the Queen. He was eventually banished from the royal court.

Cagliostro and the prostitute who pretended to be the Queen were also acquitted, while the forger Villette was found guilty and was banished. The Comtesse’s husband was sentenced to servitude.

The mastermind, Comtesse Jeanne de la Motte, was found guilty and was severely punished. She was shipped, branded the letter V as a voleuse-thief, and imprisoned. She eventually managed to escape by disguising herself as a boy and came to London in 1789, where she published her memoirs.

In 1791, the Comtesse died after falling off a window as a debt collector was chasing her: a picture of a tragic ending and poetic justice finally catching up with her.

However, a more tragic death would come upon the Queen two years later, in 1793. The public trials and execution of the Comtesse and other events led to the rise of the masses, clamoring for the end of the French monarchy. It sparked the French Revolution and Marie Antoinette’s public execution.

After being overthrown, King Louis XVI was tried for treason and guillotined by the National Convention in January 1793. After being imprisoned, Marie Antoinette was guillotined in October of the same year.

——–

Sources:

https://www.history.com/news/marie-antoinette-diamond-necklace-affair-french-revolution

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1970/affair-of-the-diamond-necklace

https://library.csi.cuny.edu/c.php?g=619342&p=4310783

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG212687

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG212687