Our planet hasn’t always looked the way it does. For millions of years, Earth was so drastically different from the world we know that it might as well have been a different planet!

In August 2024, paleontologists made an exciting find: matching sets of dinosaur footprints. Simply finding dinosaur footprints, hundreds of millions of years after they were made, is remarkable in its own right. But these footprints were even more special. They were perfectly matched but were found on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Let’s travel millions of years into the past, back to the Mesozoic era, to see how this became possible.

When Dinosaurs Could Walk from Brazil to Cameroon

If you’re fond of solving puzzles, you might have noticed how the eastern coast of South America and the western coast of Africa seem to fit together like pieces of a puzzle.

Even though the two continents sit on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean, this wasn’t always the case. Around 200 million years ago, before the dawn of the Cretaceous period, South America and Africa were joined together as part of the supercontinent Gondwanaland.

During the Jurassic period, which preceded the Cretaceous, Gondwanaland began to break apart due to plate tectonics, a geological phenomenon that causes continental drift. By the dawn of the Cretaceous period, 145 million years ago, the two continents are believed to have been separated by a newly formed and still-widening Atlantic Ocean.

The dinosaur footprints in this new study are younger, estimated to have been made around 120 million years ago. What this tells us is that the separation of South America and Africa hadn’t been complete, and there was at least one point where the two landmasses were still connected.

It had been a corridor running from the Borborema region in Brazil to the Koum Basin in Cameroon. Today, these two locations are separated by approximately 3,700 miles and an entire ocean. Back then, it was a short walk for dinosaurs, spanning about 620 miles.

The Earth’s average temperatures during the Cretaceous were hotter than today. This created a greenhouse-like environment, with lush jungles that teemed with life.

Since this last land bridge between Brazil and Cameroon lay close to the equator, it’s safe to assume that the landscape resembled the equatorial rainforests of today, with the addition of dinosaurs.

Imagine a dense, green landscape dotted with rivers and lakes. These newly formed water bodies would go on to increase in size and come together to form the Atlantic Ocean. Much earlier, however, it was barely a fraction of its size.

The ocean was eventually created by the gradual separation of two continental plates that would ultimately become South America and Africa. These water bodies were surrounded by plentiful deposits of muddy sediments. It was in this soft soil that dinosaurs would leave their footprints, proving that Brazil and Cameroon were still connected even as the rest of their respective continents started to pull apart.

Studying the Dinosaur Dispersal Corridor

The study of this dinosaur highway was published by the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science. A team of five paleontologists, led by Louis L Jacobs of the Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, took on the task of analyzing over 260 trace fossils from the Borborema Plateau and the Koum Basin to look for similarities.

The four other co-authors of this study are Lawrence J Flynn, Christopher R Scotese, Diana P Vineyard, and Ismar de Souza Carvalho.

Unlike true fossils, which contain the actual physical remains of flora and fauna, dinosaur footprints are considered trace fossils. Trace fossils do not contain any physical remains, but offer evidence of how animals interacted with their environments. The technical term for trace fossils among paleontologists is ichnofossils.

The study was conducted to honor the memory of Martin Lockley, a paleontologist who specialized in ichnofossils before passing away in November 2023.

Its findings give us invaluable information about the movement patterns of animals between the two continents. As Gondwanaland broke apart, this dinosaur dispersal corridor must have been an important link connecting the two halves of the supercontinent during the early Cretaceous period.

Once this narrow strip of land was swallowed by the emerging ocean, it would send the wildlife and plant life of both continents onto drastically different genetic and evolutionary paths.

Speaking about the significance of this study to the New York Times, lead author Louis L Jacobs said, “Dinosaur tracks tell you things bones won’t… It shows how they moved, where they moved, whether they moved alone or with others. It’s a different way of looking at the past, because there is different information contained in the footprints.”

Finding the Dinosaurs Whose Footprints Spanned an Ocean

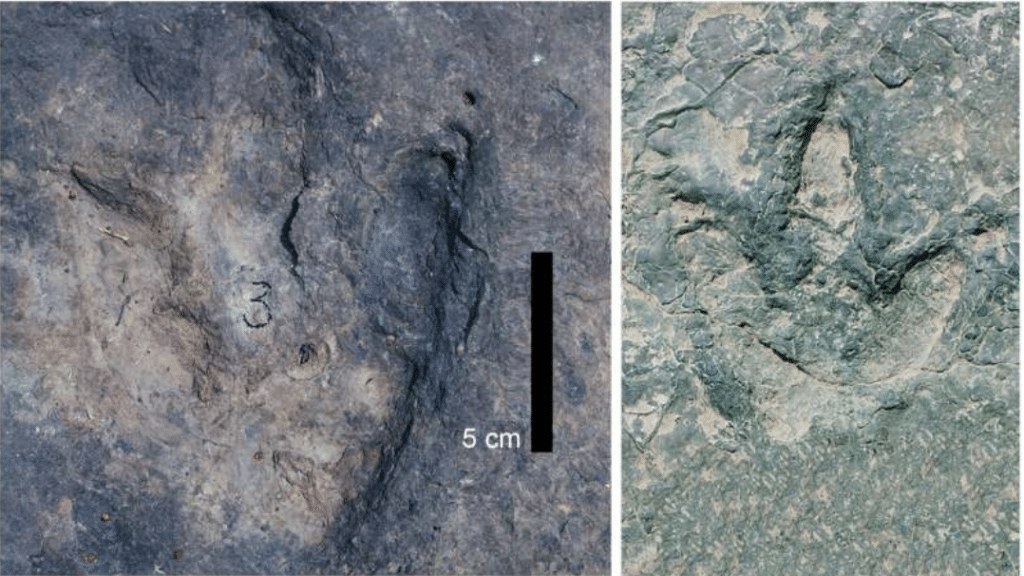

Since the dinosaur footprints found in the Borborema-Koum Basin corridor are trace fossils, the paleontologists could not conclusively identify which species of dinosaur left the tracks. However, like all ichnofossils, they contain enough information for an educated guess.

There are two types of tracks found in the early Cretaceous dinosaur dispersal corridor. The more common type is a tridactyl (three-toed) footprint, made by a bipedal (walking on two legs) dinosaur. This allows us to identify the owners of these footprints as carnivorous theropod dinosaurs, a lineage that would give rise to the infamous Tyrannosaurus rex during the late Cretaceous.

Since there were carnivores in the corridor, there must also have been abundant prey for them to feed on. The other types of tracks could have been made by sauropods, a group of herbivorous browsers known for their long necks, or by ornithischians, a diverse superfamily of herbivores that included horned ceratopsians, armored ankylosaurians, and plated stegosaurians.

Our planet has always supported a dazzling amount of biodiversity. This new study is another example of how life has always found a way to traverse our planet, even when its very configuration was being changed by geological forces.