Last updated on July 29th, 2022 at 10:32 pm

In the 60s BC, the Roman general Gnaeus Pompeius, later known as Pompeius Magnus or Pompey the Great, undertook a series of wars in the Eastern Mediterranean on behalf of the Roman Republic.

These were famous conflicts, as Pompey won successive victories, bringing the remainder of the Seleucid Empire in Syria under Roman occupation and reducing the Kingdom of Judaea into a client state.

Only one individual in this world was close to a match for Pompey. This was King Mithridates VI of Pontus, who became known as Mithridates the Great. For years he fought off Roman efforts to interfere in his kingdom and caused Rome serious problems.

But Mithridates’ accomplishments were even more unusual, for the King of Pontus had been systematically poisoning himself for many years. Here we explore the strange story of the poison king.

The Kingdom of Pontus

The Kingdom of Pontus, which Mithridates the Great would one day come to rule had, emerged on the Black Sea shores of northern Turkey in the 280s BC.

A Persian general called Mithridates carved out his small principality here during the decades of political and military chaos which followed the collapse of the empire of Alexander the Great.

The Kingdom of Pontus, which he established, remained a small power here along the southern edge of the Black Sea for the next century and a half.

The major power of the wider region at the time was the Seleucid Empire, which had been established by one of Alexander’s former generals, Seleucus Nicator, and which stretched from central Turkey south-east into the Levant and across much of Mesopotamia and Persia.

However, the Seleucid Empire entered a period of pronounced decline in the mid-second century BC, leaving a power vacuum in the region. It was right around this time that Mithridates succeeded as Mithridates VI of Pontus.

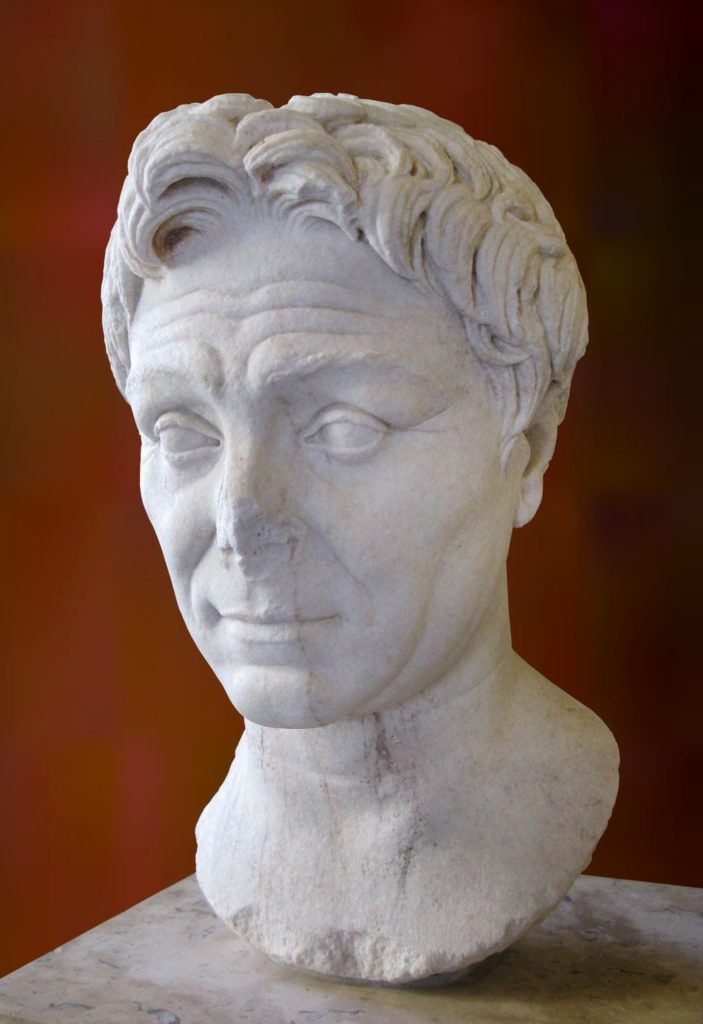

Mithridates the Great

Mithridates was still just a teenager when he ascended to the throne of Pontus around 120 BC.

Despite his youth, he quickly began taking advantage of the weakness of some of his neighbors, notably the Seleucid Kingdom, but also some of the Greek powers to the west, the Kingdom of Bithynia to the south, and the Kingdom of Armenia to the east.

In the first years of his reign, he conquered Colchis in what is now Georgia and expanded Pontus’s control over much of the eastern end of the Black Sea.

Eventually, he also expanded along the northern shores of the sea as well, capturing the Bosporus and the Crimean Peninsula, areas that had been colonized for centuries by the Greeks.

With this complete, he made Pontus the pre-eminent naval power of the Black Sea. These conquests, however, had been relatively easy compared with what he attempted next.

In the 90s BC, Mithridates began attempting to conquer much of what was then known as Asia Minor, which we would call Turkey today. This brought him into conflict with Bithynia and some other powers.

These soon turned to the Roman Republic, which had begun expanding into the Eastern Mediterranean in the middle of the second century BC, for aid. Thus, Mithridates and Pontus ended up at war with Rome from 89 BC onwards.

Immunity to Poison

The Mithridatic Wars would last on and off between Pontus and Rome for nearly a quarter of a century.

And it was in fear of the possibility that Rome, the Bithynians, or one of his other enemies would try to dispense of him in some alternative way that Mithridates began poisoning himself.

His father, Mithridates V, had been killed by a lethal dose of arsenic, and Mithridates had always sought ways to avoid a similar fate. Thus, he began taking sub-lethal amounts of arsenic himself when he became king. The goal was to familiarize his system with it so it could never kill him.

Over the years, he became increasingly obsessed with developing immunity to different poisons, such that he had a daily regimen of taking small doses of poisonous substances and several anti-toxins to combat their effects.

For instance, one substance some believe he ingested was the blood of Pontic ducks, which were known to consume hellebore and hemlock, two poisonous substances which left trace amounts in the blood of the ducks.

In this way, Mithridates was said to have built up immunity to all the most widely used poisons of the ancient world.

Moreover, as the years went by, he and scholars whom he employed to search through volumes on toxicology at the Great Library of Alexandria and elsewhere had worked out complex recipes for a universal antidote to any poison which might be used on him. This later became known as the ‘theriac’ and became famed for centuries across Europe.

The End of the Kingdom of Pontus

In the end, it wasn’t poison that got Mithridates, but war with Rome. In 73 BC, the third conflict between Pontus and Rome of Mithridates’ long reign broke out.

Unlike the first two conflicts, the Third Mithridatic War saw Rome commit massive resources to the Eastern Mediterranean. Mithridates succeeded in acquiring an ally in Tigranes II of Armenia. Still, the Romans built up an alliance of several regional powers whom Mithridates had alienated, notably Bithynia and Galatia.

The war was an intense fight for several years, but when Pompey the Great was appointed to command the Roman effort in 66 BC, he quickly managed to overcome Mithridates’s armies.

The King of Pontus fled to his territories in the Bosporus on the northern shores of the Black Sea. There he intended to gather a new army and attempt to march overland along the course of the River Danube and descend on Italy.

However, before he could do this, his subjects clarified that he had lost their support. Disillusioned, the old king is said to have tried to commit suicide by poisoning himself.

Finding himself immune to every toxin he consumed, he instead had to order one of his bodyguards, Bituitus, to kill him with his sword. The latter tale seems a little too fanciful to be accurate, and it seems more plausible that Mithridates was actually betrayed by his own son, Pharnaces, who had revolted shortly before this.

Mithridatism and the Theriac

Mithridates’ legacy was extensive, not just as one of the most formidable enemies Rome ever faced, but because the concept of developing immunity to poison by consuming trace amounts became known after his time as Mithridatism.

The supposed universal antidote against any poison many believed he developed, the theriac, took on a legendary status in Europe after that.

As late as the seventeenth century, European doctors and apothecaries were still selling concoctions that were meant to mirror the Pontic king’s potion.

These might contain dozens of ingredients, including snake, a wide array of plants and herbs, the blood of various animals, and many other substances, all of which were placed into a flask and left to ferment for upwards of a year.

People used this theriac to try to cure all manner of sicknesses. Sales of versions of it ballooned when the Black Death hit Europe in the mid-fourteenth century.

Thus, a millennium and a half after his own time, Mithridates was still a well-known figure in Europe, owing to his reputation as the poison king.