The world we live in today would not exist the way it does have it not been for the Industrial Revolution. Beginning in England in the 1760s and 1770s, a series of significant changes occurred in the country’s economy, transforming Britain.

Other nations soon adopted these innovations, notably the United States, Germany, France, and Russia. The scale of the change was immense. In 1750, Europe was still a largely subsistence society where most people lived in the countryside and farmed.

Factories, trains, railways, steamships, and electricity did not exist. But a century later, it had all changed. Thousands of kilometers of railway lines were laid down yearly to connect the world and create the First Age of Globalisation.

Steamships were beginning to traverse the Atlantic Ocean in days rather than weeks. Factories, with their huge chimneys billowing out coal smoke, were ubiquitous across Britain’s industrial cities, and every year more and more people flocked to the cities to become urban laborers.

For instance, Birmingham was a town with a population of approximately 30,000 people in 1750. By 1850 a quarter of a million people lived there. And with this growing industrialization, Britain became the world’s economic powerhouse.

In the nineteenth century, the country was the world’s foremost superpower. The question is, why did this happen here? Why did the process of transforming the modern world occur in a small country on the periphery of Europe?

The Agricultural Revolution

There are many reasons why the Industrial Revolution began in England, but perhaps the most important one was that the Agricultural Revolution preceded it.

In the first half of the eighteenth century, several innovations were introduced into farming in England, Wales, and Scotland, hugely improving productivity.

For instance, Jethro Tull invented the first modern seed drill in the early eighteenth century. This allowed for much more effective sowing of seeds and increased crop yields.

Other developments such as better livestock breeding, crop rotation, and new fertilizers meant that the output of the average agricultural worker more than doubled during the eighteenth century.

This meant fewer individuals had to work on farms or tend herds to produce the same amount of food. This meant, in practice, that hundreds of thousands of individuals were suddenly available to begin working in other industries, and proto-industrialists could obtain their labor at a lower cost. The Agricultural Revolution was a vital precursor for the Industrial Revolution to start.

The Lead-up to the Industrial Revolution in England

Of course, industrialization did not just appear out of nowhere. It was developed from existing elements of the English economy. In the late medieval and early modern periods, business people known as proto-industrialists began to develop businesses across England that concentrated, like all industries, on taking raw materials and transforming them into manufactured products.

This could involve activities such as the smelting of iron ore in large ironworks or the manufacture of glass, but the proto-industry which predominated across England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries concerned textiles.

Farmers in England and Wales produced an abundant amount of wool which could be made into clothes, while cheap cotton was also becoming available from England’s colonies in North America by the eighteenth century. As a result, many proto-industrialists had begun to set up workshops in cities like Manchester and Birmingham, where large amounts of textiles were produced from these raw materials.

England was in a good position to lead the way in industrialization as it had this proto-industrial base already set up. In contrast, there was little proto-industry in a country like Spain or Portugal, for instance, by the eighteenth century.

Innovation in England

The foremost reason for the Industrial Revolution beginning in England was the sheer number of inventions that came out of inventions at this time that drove industrialization.

We will concentrate on just two that emerged at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. First, in the mid-1760s, a weaver and carpenter from northern England named James Hargreaves invented a new multi-spindle spinning frame for spinning cloth.

The Spinning Jenny device allowed a weaver to work on eight spools of cloth or more at once. Then a decade later, a Scottish inventor called James Watt developed the first highly efficient steam engine. With these two innovations, a proto-industrialist could now use steam power to power machines like the Spinning Jenny.

The upshot was that a single worker operating a Spinning Jenny could produce multiple times the amount of cloth and textiles their counterpart could have in 1700. And proto-industrialists had come up with a way of maximizing the profitability of these innovations.

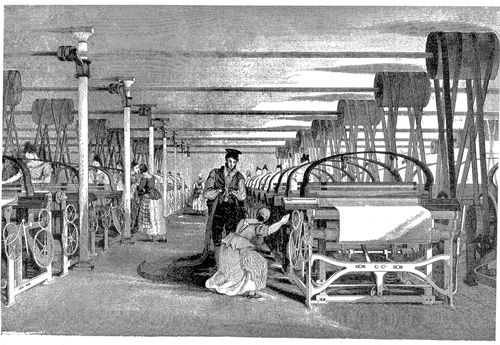

Beginning in the 1760s, they began setting up the first modern factories. Before this time, cloth and textile weaving had primarily been carried out in people’s homes or small workshops.

But in the 1760s, proto-industrialists began constructing large buildings in which dozens of Spinning Jennies were housed. Workers would come to the factory and operate the machines for wages from the owner. And with the changes in the labor market that the Agricultural Revolution had brought about, there was no shortage of men and women looking for work.

Thus was born the Industrial Revolution, and as more and more people began to realize the profits that could be made from this business model, factories began to appear all over England.

England’s Coal Deposits

Of course, there was one final ingredient needed. Watt’s steam engine required fuel of some kind to power it. Many medieval and early modern societies relied on wood for their energy needs.

But wood is not a high-energy fuel. The forests of England and Ireland had been utterly devastated in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries due to over-exploitation to fuel the ironworks in both countries. However, England had other fuel types.

Since the sixteenth century, the country had become increasingly reliant on coal for its energy needs, abundant amounts of which were available in the town of Newcastle in the north.

London was effectively heated in the winter by Newcastle coal. And so, when the steam engine took off in the 1770s and 1780s, the number of coal mines expanded across the north of England. Here was England’s last ingredient to successfully develop its industrial output, a large supply of high-yield energy.

Northern coal, combined with innovations such as the Spinning Jenny and the Watt steam engine, as well as abundant cheap labor and raw materials like wool and cotton, allowed the Industrial Revolution to begin in England. The world started to change very quickly after that as a result.

Sources

Gordon E. Mingay, ‘The “Agricultural Revolution” in English History: A Reconsideration’, in Agricultural History (1963), pp. 123–133.

Franklin F. Mendels, ‘Proto-industrialization: The first phase of the industrialization process’, in The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 32, No. 1 (March, 1972), pp. 241–261.

John Styles, ‘The Rise and Fall of the Spinning Jenny’, in Textile History, Vol. 51, No. 2 (2020), pp. 195–236.

Gregory Clark and David Jacks, ‘Coal and the Industrial Revolution’, in European Review of Economic History, Vol. 11, No. 1 (April, 2007), pp. 39–72.