Last updated on January 7th, 2023 at 12:35 am

The term “ponzi scheme” is a common business term that describes when investors pay money into a nonexistent enterprise, and their money is returned to earlier investors as fake payments.

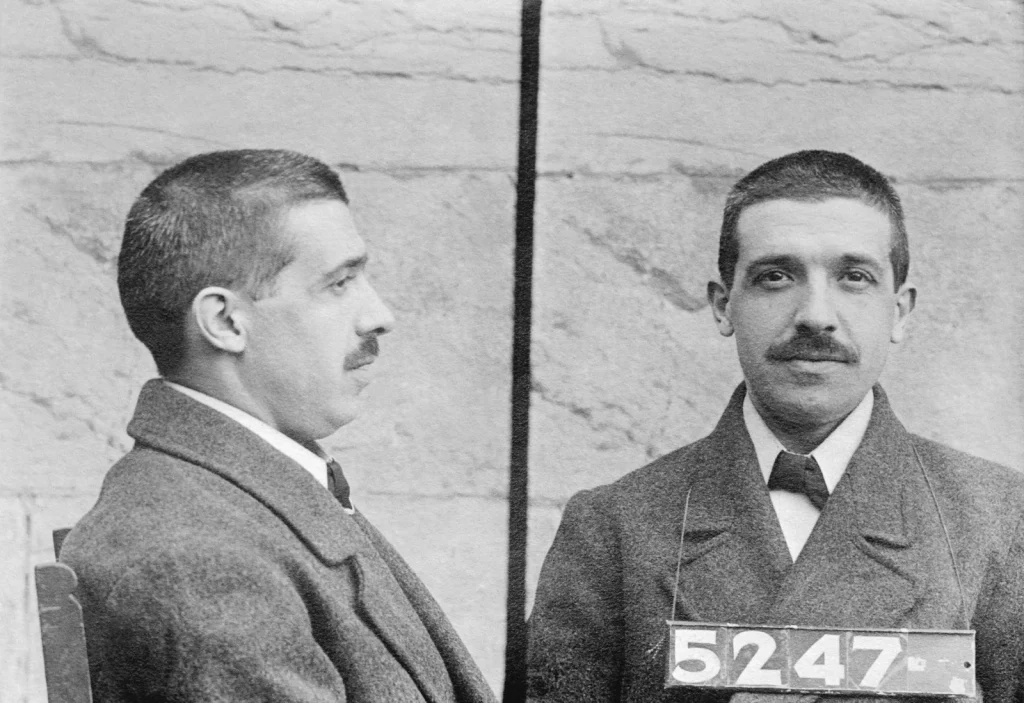

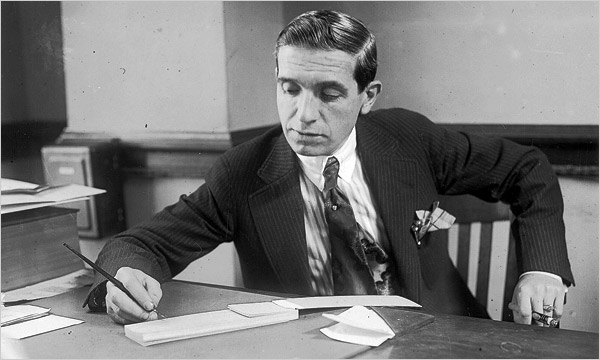

But many may not know that the term originated from Charles Ponzi — an Italian con artist and swindler. They used his charismatic charm and persona to invest in his made-up businesses.

Who was Charles Ponzi, and how did his name become synonymous with fraud?

From rags to riches

Born in 1882, Charles Ponzi lived in Lugo, Italy, at the turn of the 20th century. While his family had been initially well-to-do, they had fallen on hard times, and Ponzi spent much of his life growing up poor.

He eventually got accepted into the University of Rome La Sapienza to study but ended up spending all of his money and shortly found himself broke and without a degree.

With little to his name, he migrated to the United States in 1903 and began learning English. But as he integrated into his new life, he started to dream of ways to generate wealth.

The man who claimed to only have “$2.50 in cash and $1 million in hopes” quickly found a way to earn a buck.

Ponzi came up with the idea for an international trade journal where he thought he could make a profit selling advertising. But, the bank he sought a $2,000 loan from denied his application, and Ponzi found himself back at square one.

A claim to fame

But, in August 1919, a new idea came to Ponzi. He received a piece of mail that contained an international reply coupon.

The small piece of paper allowed the recipient of international mail to respond without paying for the return mail.

The postal coupon, otherwise known as an IRC, could be exchanged for stamps and potentially a profit if the country where the IRC was purchased had different rates from the United States.

Ponzi’s brain kicked into overdrive. Ponzi claimed he could purchase large quantities of the IRCs overseas and turn them into profit in America.

He quit his job as a translator and started a business around exchanging and profiting off of the IRCs from other countries.

But first, he needed the initial investment to get going. So Ponzi went to several of his Boston friends and asked for their money to get going, promising that he would get them a 50% profit in 45 days and a 100% profit in 90 days.

His charming personality and suave demeanor got him far, but not far enough. That’s why he hired and trained sales agents who would go out and try to obtain more investors to buy into his idea.

Promising the sales agents a commission, these sales agents would pitch Ponzi’s IRC scheme to other wealthy individuals, ensuring Ponzi stayed out of sight and out of mind to those with deep pockets.

Ponzi’s Downfall

Soon, investors began to realize that the math wasn’t adding up. A man named Joseph Daniels filed a $1 million lawsuit against him in July of 1920, claiming that Daniels was owed part of Ponzi’s fortune for money not returned.

By this time, Ponzi lived in a 12-room mansion, had multiple servants, wore fine clothes, and purchased diamonds for his wife. His life was dripping in opulence and luxury — a far departure from the $2.50 he got off the boat 17 years earlier.

But, behind the scenes, a reporter at the Boston Post was investigating Ponzi and his business practices.

Once the newspaper got word of the lawsuit Daniels was filing, they ran a front-page investigative feature on the suspicious businessman, pegging his net worth at $8.5 million.

Today, that money would total over $126 million.

Things around Ponzi quickly began to fail after the article came out. For the first time since World War I, the U.S. Postal office changed the IRC rate less than a week after the Post’s report.

While they claimed the sudden change in pricing had nothing to do with the Ponzi article, they publicly said it would be impossible to do what Ponzi had founded his business on.

He became under initiate by the federal authorities and under the advice of his publicist, agreed to cooperate with the investigation.

Soon, his investors flocked to his office and asked for their investment back. Even under pressure, Ponzi maintained a cool, calm, and collected demeanor.

Ponzi was able to forgo major consequences for another couple of months until it all came crashing down in August of 1920.

The Boston Post came out with another front-page story about Ponzi and fraudulent checks he wrote 13 years earlier in Montreal.

That same afternoon, the bank seized Pnozi’s funds due to irregularities.

The next 15 years followed with Ponzi in and out of prison on federal counts of mail fraud and larceny.

After being released for the last time in 1934, Ponzi was deported back to Italy, telling reporters, “I went looking for trouble, and I found it.”

Back in Italy, Ponzi spent his last years largely in poverty, working here and there as a translator. He passed away in 1949.

Ponzi schemes today

Today, a Ponzi scheme has become a common term used to describe a business scam that “robs Peter to pay Paul.”

It’s characteristically led by a charismatic and energetic scam artist, who exploits potential investors with a fear of missing out on a golden opportunity.

And while it’s been nearly 100 years since Charles Ponzi laid out his first scam, not much has changed.

Last year alone, federal investigators discovered 60 major Ponzi schemes totaling over $3.25 billion in fraudulent scams.

Many became familiar with the illegal business practice named after Charles Ponzi when Bernie Madoff was found guilty of running the largest Ponzi scheme in American history, worth nearly $64 billion.

While Charles Ponzi might have died alone and mostly poor, his name carries with it a denotation of fraud and scheming — something he might be proud of.