There are mafia crime bosses, there are gangsters, and then there’s Crazy Joe, a blue-eyed friend who stood barely 5 feet, 6 inches tall yet, after his untimely death in New York City’s Little Italy, left a colossal legacy in his wake.

The History of organized crime in America isn’t complete without including Joseph Gallo, a man who authored not one but two bloody mafia gang wars. But Joey wasn’t always ‘Crazy.’

So what happened to Crazy Joe Gallo, and how did he rise to prominence from obscurity at the peak of organized crime in America?

Joe Gallo Early Life

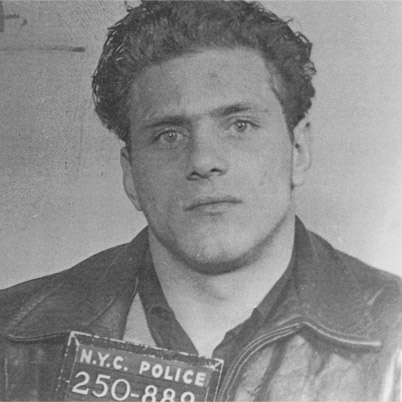

Joseph Gallo, alias “Crazy Joe,” was an Italian American gangster and a capo of New York City’s Colombo criminal family.

He was born on April 7, 1929, to Umberto and Mary Gallo in the New York City neighborhood of Red Hook, Brooklyn. During the prohibition era, Umberto worked as a bootlegger. His various smuggling and racketeering stints meant that Joey and his siblings weren’t exactly discouraged from participating in local crime.

Crazy Joe had somewhat of a dysfunctional early life. Shortly after finishing his elementary schooling at P.S. in Kensington, he dropped out of high school at sixteen.

After doctors at the Great Lakes Naval Hospital determined that he was “temperamentally unsuitable for continued military service characterized by restlessness and a neurological disorder,” he was honorably discharged from the U.S. Navy in 1946.

In 1949, Gallo found a new role model in Tommy Udo, the main character in the 1947 film noir Kiss of Death, which featured one of the most terrifying scenes in crime cinema history — Udo pushing the mother of s mobster down a set of stairs to her death in a wheelchair after tying her up with an electrical line.

He was believed to have modeled his behavior after the gangster persona, imitating him and reciting the movie dialogue.

Four years later, his atypical behavior landed him in Kings County Hospital. Gallo was transferred to the psych unit for treatment after the magistrate determined that he could not comprehend the charges against him before his arraignment on burglary charges. The psychiatrists at Kings County Hospital later diagnosed Joey with paranoid schizophrenia.

Early Criminal Career

Crazy Joe began his criminal career with his brothers as an enforcer and hitman for Joe Profaci of the Profaci crime family. The American Mafia was the dominant force at the time.

New York City’s shady dealings were split among five crime families. Foot soldiers under the command of captains and skippers ran gambling, loansharking, extortion, drugs, racketeering, labor, and a wide variety of other criminal dealings.

It was the height of American organized crime’s strength and influence, and the Gallo Boys were especially eager to make their mark.

Being from Red Hook, Brooklyn, the boys fell under the jurisdiction of Frank “Frankie Shots” Abbatemarco and were mentored by the prolific Profaci crime family capo. He taught them the ins and outs of the mafia’s activities, and the Gallo Boys quickly made a name for themselves. This was especially true once they created a “union” whose main objective was to extort local bar owners.

Gallo’s talent truly shined as a criminal. He directly handled several criminal businesses, including floating dice and high-stakes card games, number games, and extortion shakedowns.

He was also a capo-level manager at his father’s loan-sharking outfit and his brother, Larry Gallo’s vending machine and jukebox operations. Over the next couple of years, Joey secretly acquired ownership of two sweatshops in the Garment District and several nightclubs in Manhattan.

In 1957, the supreme leader of the Profaci crime family, Profaci himself, commissioned the Gallo crew to assassinate crime boss Albert Anastasia.

Anastasia was one of the most dreaded mafia bosses in the country. He was well renowned for his aggressive demeanor and the numerous murders he was responsible for either directly or indirectly through Murder Inc; a transnational murder-for-higher mob hit squad. Failure wasn’t an option for the Gallos.

On October 25, while Anastasia was unwinding in his barber chair at the Park Sheraton Hotel in midtown Manhattan, two men stormed in — facial features masked by scarves — pushed the barber aside, and shot the Gambino leader dead in a shower of gunfire. The killers vanished after, never to be apprehended by the law.

While authorities were never able to nail a suspect for the murder, the identity of the assassins wasn’t much of a secret in the underworld, as future crime lord Carmine Persico subsequently claimed that he and Gallo had assassinated the mafia boss, teasing that he was one of Gallo’s “barbershop quintet.”

First Colombo War

After completing many Profaci-sanctioned commissions, including the murder of crime boss Anastasia, the Gallos believed they were being underpaid, exploited, and undervalued.

The Gallos took some important Family members hostage to express their discontent, including the underboss (who was also Profaci’s cousin and brother-in-law), a few lieutenants. Profaci himself came dangerously close to being abducted as well.

Crazy Joe being who he was, intended to kill some of the hostages to demonstrate to everyone that the Gallos were serious about their business, but his brother Larry, the Gallo leader at the time, rejected that plan.

Profaci immediately agreed to most of the reform and fairness demands, but only on the surface. The Gallos subsequently freed their captives.

However, unsurprisingly, Profaci, after getting back his family’s lieutenants, broke his word and declared war. He convinced Carmine Persico, a Gallo higher up at the time, to change sides.

Carmine kept his new allegiance a secret from his old friends. The Gallos only discovered his betrayal when he almost succeeded in strangling Larry Gallo to death during a rebel meeting in a Brooklyn bar, only to be interrupted by a passing police officer. The Gallos began referring to Persico as “Snake,” a moniker that stuck.

The entire New York Mafia started to feel the heat as the flames of war continued to burn all over New York City. The pressure from law enforcement and the media made things difficult for the other four families, and the bosses cautioned Profaci to think of the bigger picture.

Profaci didn’t let on. Assisted by fellow boss Joseph Bonanno, he was able to stave off the Commission and continue his now blood-themed feud with the Gallos, gradually depleting their resources in terms of manpower and finances.

While both sides were trying all they could to eliminate each other, law enforcement was biding their time, ready to catch the major players in one fell swoop. In late 1961, Joey was charged with conspiracy, attempted extortion, and sentenced to seven to fourteen years in prison.

A year after Crazy Joe was sent to prison, the commission was finally able to broker a leave deal between the Gallos and Profaci. This marked the end of the first Colombo war.

Second Colombo War

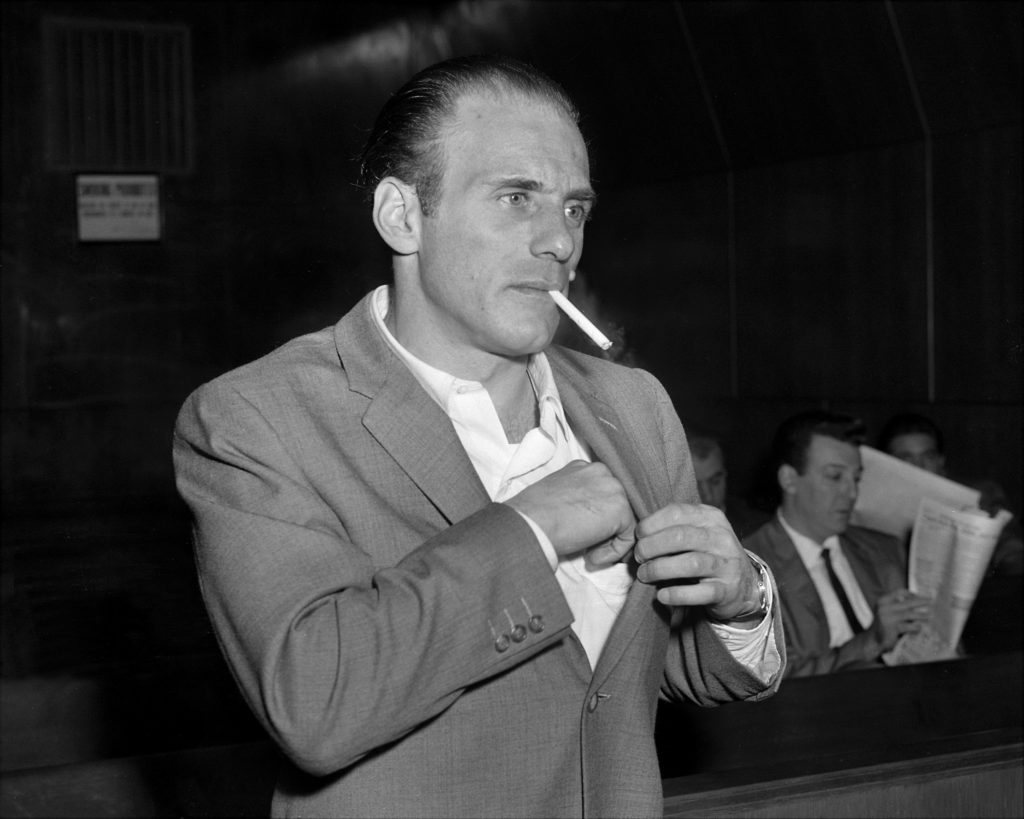

After serving an approximately ten-year jail sentence, during which time he allegedly studied up to eight books per day, Crazy Joe emerged as a self-ascribed painter and poet who impressed the upper crust of the Big Apple. Ben Gazzara, Jerry Orbach, and David Steinberg from comedy were some of the friends he made during this period.

Upon Joey Gallo’s release from custody, the Profaci family changed leaders, and his brother Larry died of cancer at 41. Joseph Colombo, one of the Gallo crew’s captives back then, during the war with Profaci, was now the new head of the family. He now commanded hundreds of men across the nation, including Joey Gallo and his crew.

Colombo gave Gallo a $1,000 gift to say “hello” and “welcome back.” A gesture that Gallo didn’t appreciate, as we’ll later come to learn.

No longer bound solely to the mob environment, thanks to his enlightening stint at the correctional facility, Gallo quickly assimilated into New York’s elite society after settling down.

In light of his new position in high society, Gallo struggled to accept his position in the mob. He was a soldier, not a boss, not a capo. He was a soldier with legendary repute and street credibility, but still a soldier. The Family head owed him nothing. He had to prove his worth just like any other foot soldier.

But Crazy Joey wasn’t about that life again. He felt that he had long since moved past that stage. Crazy Joe got into character once again. He readied his crew for war.

Joseph Colombo had to go.

On June 28, 1971, Colombo was gunned down from close range at an Italian Unity Day in Columbus Circle, New York, by an African-American gunman while preparing to address the crowd.

After shooting the mafia boss, the assailant, Jerome Johnson, dressed as a photojournalist, was shot and killed by one of Colombo’s security outfits.

Although the Colombo family largely held Gallo responsible for Colombo’s assassination, the police ultimately concluded that Johnson was the only shooter after questioning Gallo. While most of the mob speculated on why Gallo might have ordered a hit on the criminal lord, Gallo’s life continued as usual.

Fall of Crazy Joe

Around 4.30 am., on the 7th of April 1972, a short year after Colombo was murdered, Gallo and his family gathered to celebrate his 43rd birthday party at Umberto’s Clam House in Little Italy, Manhattan. Shortly after the celebrations began, gunmen stormed the restaurant, guns blazing, aiming for Joey.

According to witnesses, he sought to divert fire away from his family. Regrettably, he was no god. Fatally injured, Crazy Joe staggered out onto the street and fell. He was transferred to Beekman-Downtown Hospital in a police cruiser, where he was admitted and later declared dead at about 5:30 in the morning.

After two wars, the chronicles of the crazy kid from Red Hook, Brooklyn, closed its last chapter.

In Popular Culture

Joseph Gallo was just in his early 40s when he was shot, yet he has a lasting place in American popular culture.

Gallo’s conflict with the Profaci family was exaggerated and satirized in Jimmy Breslin’s 1969 book The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight. Kid Sally Palumbo, a stand-in for Gallo, was played by Jerry Orbach in the feature film adaptation from 1971.

Following Gallo’s murder, filmmaker Dino De Laurentiis created the 1974 film Crazy Joe, a more somber but fictitious drama about Gallo. The film, directed by Carlo Lizzani and stars Peter Boyle as the eponymous character, was based on newspaper stories written by reporter Nicholas Gage.

Gallo is the protagonist in Bob Dylan’s 12-verse ballad “biographical, Joey.” The song appears in Dylan’s 1976 album Desire.

Gallo was also the protagonist of “Joey,” a 12-verse biographical ballad by Bob Dylan. The Irishman, a 2019 Martin Scorsese film, featured Sebastian Maniscalco as Gallo.