Last updated on November 4th, 2023 at 10:23 pm

In the 1800s, some scientists posited that there existed a continent in the Indian Ocean. They believe that on this lost continent, which they had named Lemuria, lived an extinct human race called Lemurians.

These species of humans had four arms and large, hermaphroditic bodies and are generally regarded as the progenitors of the human race.

In those days, the idea of Lemuria was well accepted by some science factions and the larger society as a sort of cultural lore until modern science debunked it thoroughly.

However, in 2013, the narrative took a different turn. That year, geologists discovered evidence of a lost continent, precisely where Lemuria was said to exist, and ghosts of these old theories came back to life.

But how true is Lemuria, and what do scientists say about it?

The Lost Continent of Lemuria – The Truth of it All

The idea that a continent once existed in the Indian Ocean in prehistoric times gained popularity in 1864 when Phillip Lutley Sclater, a British Lawyer and Zoologist, wrote an article titled “The Mammals of Madagascar,” where he observed that Madagascar had more species of Lemur than Africa and India, positing that Lemur originated from Madagascar.

He added that lemurs could have migrated from Madagascar to Africa and India through an extinct land mass that stretched across the Southern Indian Ocean.

According to Sclater, this continent touched Southern Africa, Western Australia, and India’s southern point. The theory of Lemuria made inroads into mainstream science at a time when the concept of evolution was still at its cradle, and the science of continental drifts enjoyed less wide acceptance.

Leading scientists in those days adopted land bridges as the medium of animal transport as they migrated to new locations – a theory that granted more credibility to his thesis. More so, a similar view was proposed by the famous French naturalist Etienne Saint-Hilaire 2 years before Sclater’s postulations.

However, the Lemuria theory flourished on the back of notable authors and scientists who took its ideas and improved on them.

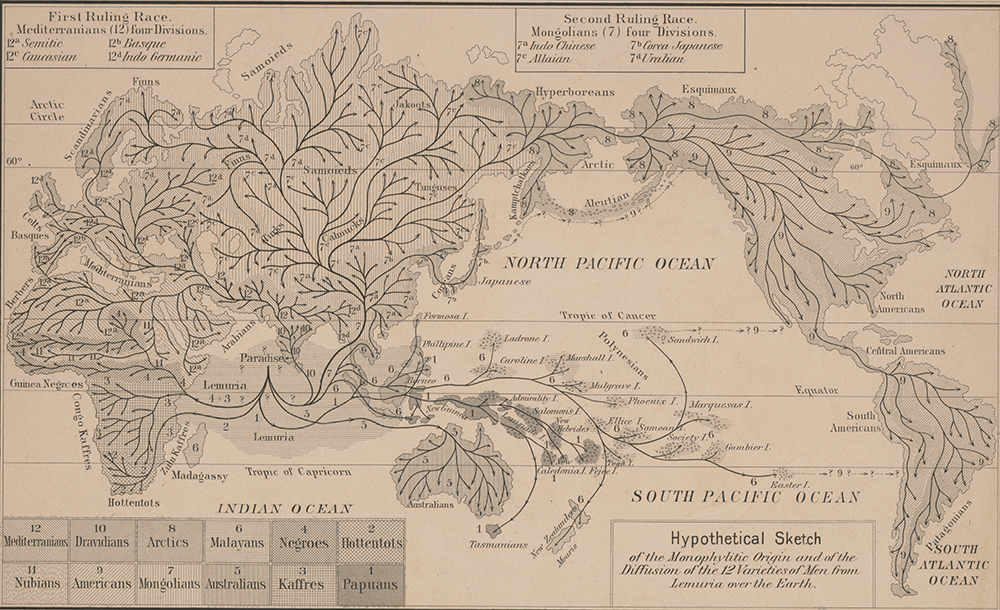

For example, Ernst Haeckel, a German biologist, published a series of works in the 1860s, all featuring a central notion that Lemuria was the land bridge that allowed humans to migrate from Asia – the true birthplace of humanity, according to popular belief in those days – into Africa.

He maintained that Lemuria was the very cradle of humankind.

Haeckel played a significant role in popularizing the Lemuria theories, helping it survive the 1800s and the early 1900s when legend had it that Kumari Kandam’s lost continent in the Indian Ocean was home to a Tamil civilization.

This belief persisted until evidence of human remains led modern science to conclude that Africa is humanity’s birthplace. Additionally modern seismologists have also discovered evidence to support the idea that plate tectonics moved otherwise intertwined continents into what we know today.

Yet, without this latter advanced scientific knowledge, the idea of Lemuria enjoyed widespread acceptance and a much further surge in subscribers to the concept in 1888 when Helena Blavatsky, a Russian author, published a paper titled “Secret Doctrine.”

According to Helena, seven human races once existed, and Lemuria was home to one of them. It was said that this race of 15-foot-tall, hermaphroditic, four-armed lived in the days of the dinosaurs. Fringe theories also supported the idea that Lemurians evolved into present-day lemurs.

As time passed, the concept of Lemuria permeated the arts and media, finding its way into comic books, movies, and novels, particularly in the 1940s. However, most ideas in those days were relegated to mere relics of a nice-sounding, 75-year-old theory and a work of fiction.

Little did they know that the theory of the lost continent of Lemuria inspired various sub-concepts of evolution, geology, and vegetational geography.

This remained so until 2013 when another discovery surfaced. W

2013 – What The Scientists Saw

By 2013, scientific theories of a possible lost continent, land bridges, and migration of lemurs had long been out of fashion. However, that year, geologists breathed life into these notions when they discovered a trace of a lost continent in the Indian Ocean.

They found fragments of granite in the southern area of the Indian Ocean, along a shelf that stretched hundreds of miles south of India, facing Mauritius. The scientists found zircon in Mauritius, amid an island that existed 2 million years ago when it rose out of the Indian Ocean as a tiny landmass due to the pressure from volcanoes and plate tectonics.

However, further findings established that the zircon found is 3 billion years old, millions of millennia before the island of Mauritius was found.

According to the geologists, this proved that the zircon had existed in a much older landform that sunk into the Indian Ocean. However, it surfaced again when the island rose from the Indian ocean.

Sclater’s theory of Lemuria was true, but only partially so. This became clearer as the geologists did away with the name “Lemuria” and instead adopted “Mauritia” as the proposed name of the lost land mass.

An analysis of geographical data and tectonics plates suggests that about 84 million years ago, Mauritia descended into the Indian Ocean; it was simply the earth taking a new form. And though this aligns with Sclater’s earlier claim, the new evidence supports little else.

Instead, Lemur likely appeared on Madagascar 54 million years ago after swimming from the island from mainland Africa.

The Theory of Sunken Continents – Lemuria and Its Parallels in History

Much of the scientific discourse around Lemuria theorized that it once served as a land bridge, though now sunken. This explains why there are biogeographic discrepancies in the modern day. However, the concept of plate tectonics directly refutes this supposition. This is not to say that sunken continents do not exist; the same science offers overwhelming proof that they do.

We’ve heard about the sunken continents such as Kerguelen Plateau and Mauritia in the Indian Ocean and Zealandia in the Pacific. But nothing supports the theory that there was once a geological formation serving as a land bridge connecting different continents, whether in the Pacific or Indian Oceans.

That India and Madagascar were once part of a larger continent was also correct, except that the continents were precisely Mauritia and another supercontinent called Gondwana.

Writers like Devaneya Payanar explained Lemuria as Kumari Kandam, a mythical sunken landmass in popular Tamil literature, claimed to be the cradle of humankind. The writer also agreed that a landmass stretching across the Kumari and Pahruli River was submerged by the ocean billions of years ago.

The theory of Lemuria found its way into the philosophy of Theosophy, represented in the theme of pseudoarcheology, and featured in debates around lost continents. Also, a fringe body of literature is dedicated to Lemuria, concepts of Lemurian fellowship, and ideas classified as “Lemurian.”

They all believed strongly that a continent once existed in ancient times, which is now submerged in the Pacific or Indian Oceans due to a geographical cataclysm. A significant attribute of the Lemuria mythology is that it housed the most complex knowledge systems from which modern-day belief sourced inspiration.

It was James Churchward who popularized and developed the concept of Lemuria from detail. He referred to it as “Mu” and identified it as a lost continent sunken deep into the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

He appropriated the idea of “Mu” from Augustus Le Plongeon’s concept of the “Land of Mu” – a term created to reference the imaginary lost continent of Atlantis. Frank Collin, a fringe author, also significantly propagated New Age and pseudoarcheological beliefs about Lemuria.

The Relevance and Uses of the Concept of Lemuria

As propounded by Sclater, the theory of Lemuria attracted fanfare and criticism, as do every work of science, whether real or fable, the notion of landbridges struck a chord amongst scientists and researchers in those days.

For instance, Etienne Saint-Hilaire had examined the relationship between animals in Madagascar and India and suggested a southern continent existed 20 years before Sclater’s theory of Lemuria entered mainstream science. Except Saint-Hilaire didn’t give the continent a name. Darwinism had just begun to enjoy wide acceptance.

This further sparked an interest in a field of science that examined the diffusion and migration of species from their evolutionary origin.

Before the concept of continental drift made inroads into popular science, biologists had frequently theorized that land-based species separated by water barriers exist because of land masses submerged into the oceans billions of years ago. Geologists who subscribed to this idea postulated that this also accounts for the similarities in rock formation spread across different continents.

Such theories, pioneered by Melchior Neumayr in 1887, sprang to prove that today’s continents were once in the same place until water submerged them and scattered them across different regions of the earth.

These and many theories were replete in the early 20th century as geologists sought to explain the geography of the modern-day continents. It was represented as a national symbol, such as in the British Indian Ocean Territory’s coat of arms, containing 12 men from Lemuria and a Latin inscription that reads, “Limuria is in our trust/ charge.”

The theory dominated while it lasted, but later theories of continental shifts and plate tectonics proved more logical and credible, and the Lemuria ended.

Bottom Line

Maybe Sclater exaggerated the conclusions of his research in “Mammals of Madagascar.” He claimed there was an extinct land bridge submerged under the sea, once inhabited by hermaphroditic human progenitors who evolved into the lemurs of Madagascar, but these didn’t stand the test of time. The theory of continental shifts and plate tectonics refuted Sclater’s ideas.

But not for long, as a 2013 research partially agreed that there was once a continent 84 years ago and named it Mauritia. It offered a different angle to explain the connection of Madagascar and Africa to the lost continent.

We can agree on one thing from all its parallels and rebuttals of the Lemurian theory. Fact or fable, there once existed a landmass between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and it’s no longer there. Whether it’s Lemuria or Mauritia, the debate continues.