How hard can it be to transport a 20-pound metal cylinder 700 miles in less than seven days? In today’s world, we would order it on Amazon, and it could be on your doorstep in a matter of hours.

Now remove roads and railroads from that equation and add extreme temperatures. This was the challenge facing those racing against time to deliver an antitoxin to Nome, Alaska, in January 1925.

The challenge of disease at the edge of the world

The 1920s was an inflection point in technology, and Nome was at the outer edge of our ability to extend human effort. Founded in 1900 and the site of the Alaskan Gold Rush, its population grew to 40,000 during its peak. However, by the 1920s, that population had dwindled to less than 4,000 if you counted the native Inuit people in the area.

Even today, Nome has no rail or road connections with the rest of the world. The only ways to get there are via boat or plane. In the winter of 1925, both of these options were unavailable.

Ice prevented maritime traffic, and the planes of the era could not withstand the extreme weather that saw temperatures on the ground drop to -60 degrees Fahrenheit, coupled with strong winds. As a result, fabric wings were shredded, and early aircraft engines froze solid.

This was the situation that faced the community when, in January 1925, the local physician Dr. Curtis Welch diagnosed the first case of diphtheria, a virulent disease with a high fatality rate.

The memory of the Spanish Flu epidemic that had taken thousands of lives in the sparsely populated region less than seven years earlier was still fresh in Welch’s mind. He immediately notified the town’s leadership of the outbreak, and the mayor immediately established a quarantine.

However, because the disease had already spread throughout the community, the risk continued.

Diphtheria was a widely feared disease in the early 20th century. In the 1920s it resulted in 100,000-200,000 cases and 15,000-20,000 fatalities annually, most of them children.

An antitoxin had been developed in the 1890s to counteract the bacterium that caused the disease. This was commonly stockpiled to counteract periodic outbreaks. However, this antitoxin degraded fairly rapidly and had to be replaced regularly.

Nome was at the far end of the technological supply line. All goods that could not be produced locally had to be stockpiled, as winter weather routinely cut off the community. Dr. Welch’s supply of diphtheria antitoxin had expired the summer before. The replacement shipment had not arrived before the ice closed down the port for the winter.

This reality was at the heart of the emerging crisis. Nome immediately alerted the territorial authorities in Anchorage, but time was not on the side of its residents. The disease was making rapid progress in the population. Furthermore, the shelf life of the delicate antitoxin under the expected conditions was less than a week.

First, sufficient supplies of the antitoxin had to be found to ship to Nome from other parts of the territory (Alaska would not become a state for another 34 years).

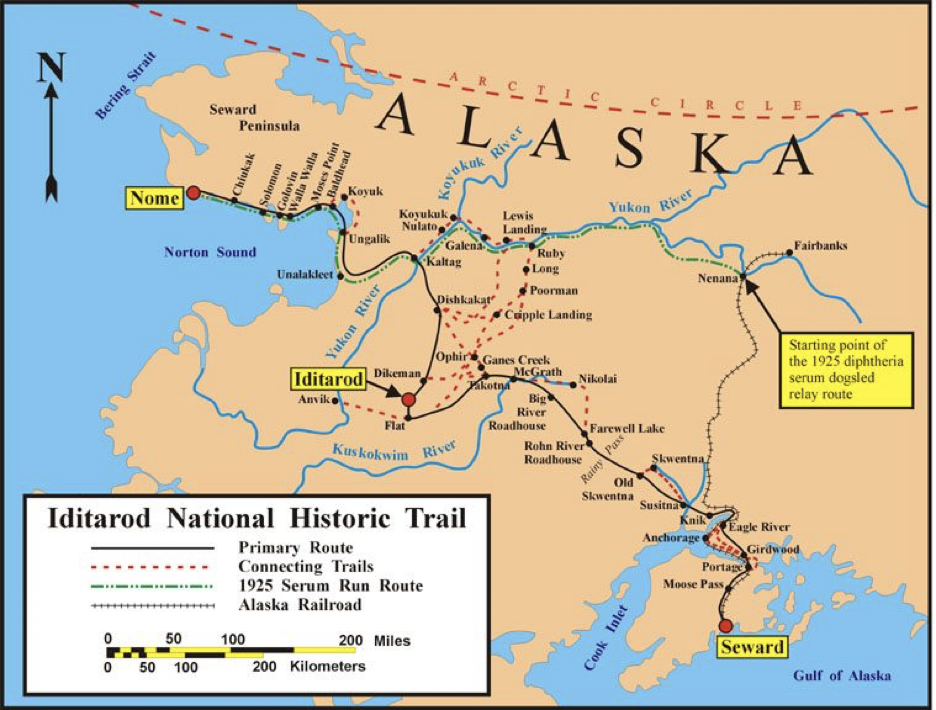

Any new antitoxin would have to come from the continental United States, thousands of miles by sea and rail. This was beside the gap between Nenana and Nome, where the rail line ended. While supplies were immediately dispatched from Seattle, they would not arrive in time.

Instead, the territorial health department found 300,000 doses in Anchorage. They wrapped the vials in blankets and placed them inside a metal cylinder for transport. The entire package weighed only 20 pounds. Those 20 pounds could save the lives of hundreds, if not thousands, of residents in and around Nome.

The Run

While flying the serum to Nome seemed like the logical course of action, the aircraft available were too frail and unsuitable for the fierce weather expected along the route. It would be another decade before aircraft were sturdy enough to face winter conditions in Alaska.

Instead, the authorities staged a relay of dogsled mushers from Nenana, where the railroad ended, to Nome. In the end, 20 teams staged along the route. Some set out from the western end and had to do a circuit outbound and turn around back towards Nome. This is how Leonhard Seppala covered 261 miles but only carried the serum for 91 of those.

In all, 20 teams and dogs and mushers took part in the relay of the canister for almost 700 miles.

The Serum Run Mushers of 1925

| Musher | Leg of Serum Run | Miles |

| “Wild Bill” Shannon | Nenana to Tolovana | 52 |

| Edgar Kalland | to Manley Hot Springs | 31 |

| Dan Green | to Fish Lake | 28 |

| Johnny Folger | to Tanana | 26 |

| Sam Joseph | to Kallands | 34 |

| Titus Nickoli | to Nine Mile Cabin | 24 |

| Dave Corning | to Kokrines | 30 |

| Harry Pitka | to Ruby | 30 |

| Billy McCarty | to Whiskey Creek | 28 |

| Edgar Nollner | to Galena | 24 |

| George Nollner | to Bishop Mountain | 18 |

| Charlie Evans | to Nulato | 30 |

| Tommy Patson | to Kaltag | 36 |

| Jack Screw | to Old Woman | 40 |

| Victor Anagick | to Unalakleet | 34 |

| Myles Gonangnan | to Shaktoolik | 40 |

| Henry Ivanoff | to meeting with Seppala | – |

| Leonhard Seppala* | to Golovin | 91 |

| Charlie Olson | to Bluff | 25 |

| Gunnar Kaasen | to Nome | 53 |

* Seppala set out from Nome, met Ivanoff outside of Shaktoolik, turned around, and carried the serum onward to Golovin, 91 miles away. With Togo, he traveled a total of 260 miles.

“Wild Bill” Shannon set out from Nenana on January 27th, 1925, at 9 pm for the first leg of the relay into a mounting winter storm. Temperatures, when he departed, had dropped to -62 degrees Fahrenheit.

You might wonder why he left in the evening instead of first thing in the morning. It made little difference. At this time of year, there were only 6-7 hours of daylight. So much of this trip would have to be done in darkness, often with almost zero visibility because of blowing snow.

The route generally followed the Yukon River until it curved southward at Kaltag. Then it went overland to the coast of Norton Sound. After that, it crossed Norton Sound over the ice floes to the southern coast of the Seward Peninsula. Nome stood at the eastern end of the peninsula.

Shannon covered his 52 miles in 8 ½ hours at the cost of two of his dogs, who died from frozen lungs, and his severe frostbite, which would scar him for life. He arrived at Tolovana at 5:30 am and handed the cylinder off to Edgar Kalland for the next leg.

Meanwhile, Leonhard Seppala set out from Nome to meet the relay. He was facing the longest trip because he had to do a round-trip from wherever he happened to meet up with the cylinder coming out the other way.

Not knowing what he was heading into, Seppala took an unusually large contingent of 20 dogs to pull his sled. He also reasoned the large team would give him some extra speed.

The relay mushers didn’t know that Seppala and his team were coming the other way, nor did they know that the Mayor of Nome had stationed additional teams on the trail across the southern coast of the Seward Peninsula.

Following the coastline around Norton Sound, Seppala was north of the Shaktoolik when he encountered Henry Ivanoff in a blinding gale on the trail.

This fortunate meeting allowed Ivanoff, the last of the “outbound” mushers, to hand off the cylinder to Seppala, who promptly turned around to make the 91 miles to Golovin, where the next musher would take over. To this point, Seppala and his team had already traveled over 150 miles from Nome.

Instead of following the coastline, Seppala took the dangerous shortcut across Norton Sound on the Bering Sea, braving unpredictable pack ice pushed around by the ocean currents.

This was a risky decision. If he and his team fell through the ice, that would be the end of the mission. On the other hand, if he stayed on the trail, he would likely arrive too late with spoiled antitoxin.

Led by his lead dog, Togo, Seppala set off across the ice for a 20 mile trek. Along the way, he repeatedly heard sounds as the ice broke up out to sea. He arrived at the north coast of the sign at 9 pm and found an Inuit family he had stayed with on the outbound leg of his travel and collapsed for the night.

The following day, all the ice in the sound was clear of the ice he had crossed just the day before as it was swept out to sea. Seppala immediately pressed on to Golovin, where he met the first mushers from Nome, still 78 miles away. His dogs collapsing from exhaustion, Seppala handed off the cylinder to Charlie Olson, the next musher.

The last musher was Gunnar Kaasen, who had less experience than most other mushers, especially under the extreme conditions prevailing along the route.

He was also leading a scratch team of dogs not used to working together, led by Balto, who needed more experience as a lead dog. So Kaasen picked up the cylinder with 53 miles to go.

Along the way, hurricane-force winds nearly blinded him and blew the sled over at one point, ejecting the cylinder into a snowbank. Kaasen dug around the snowbank with his bare hands until he found it and then pressed on to Point Safety, where the next musher was supposed to take over.

Arriving at 3 am, Kaasen discovered his relief was asleep. The storm’s ferocity had convinced the mayor to stand down the relay. Kaasen, despite the conditions, decided to press on to Nome, where he arrived at 530 am on February 2.

Kaasen delivered the cylinder into Dr. Welch’s hands 150 hours after it left the railhead at Nenana. There was some concern because the serum had frozen in the cylinder.

Dr. Welch thawed it carefully and administered the first dosage later that morning. Unfortunately, six children had passed before the serum reached Nome, but the remaining cases, including Seppala’s daughter, were all saved.

Aftermath

The saga unfolding in Alaska was a media sensation around the world. The media immediately hailed Kaasen and Balto as heroes because they were on the spot at the finish line. However, Seppala’s and Togo’s far more significant roles and heroism gradually appeared. Publicity tours happened for both mushers and their dogs. Seppala eventually sent Togo to a breeding farm.

Interestingly, almost all US Siberian Huskies are descended from him. Both dogs were stuffed after their deaths. Balto is in Cleveland, Ohio’s Natural History Museum, and Togo is in Anchorage, Alaska, at the Iditarod Museum.

Although Seppala and Kaasen were made famous by the Run, over half the distance was covered by mushers who were native Athabaskans. It would be decades before their contributions were recognized. While all the mushers received compensation from the territorial government, it was less than $500 in today’s currency.

Dogsleds remained an essential mode of transportation during the Alaskan winters into the 1960s. To this day, there are no road or rail connections between the Seward Peninsula and the rest of Alaska.

The same year as the Serum Run, the US Government passed the Kelly Act, which allowed private air mail carriers to take over US Postal Service routes.

Within a decade, aircraft could traverse the distance between Fairbanks and Nome in a fraction of the 5 ½ days it took the mushers of 1925. However, no dog sled team has ever beaten the relay’s transit time along the route. The Iditarod Sled Dog Race, commemorating the Serum Run, travels a different way.

Sources

Coppock, Mike (August 2006). “The race to save Nome”. American History. 41 (3): p. 60)