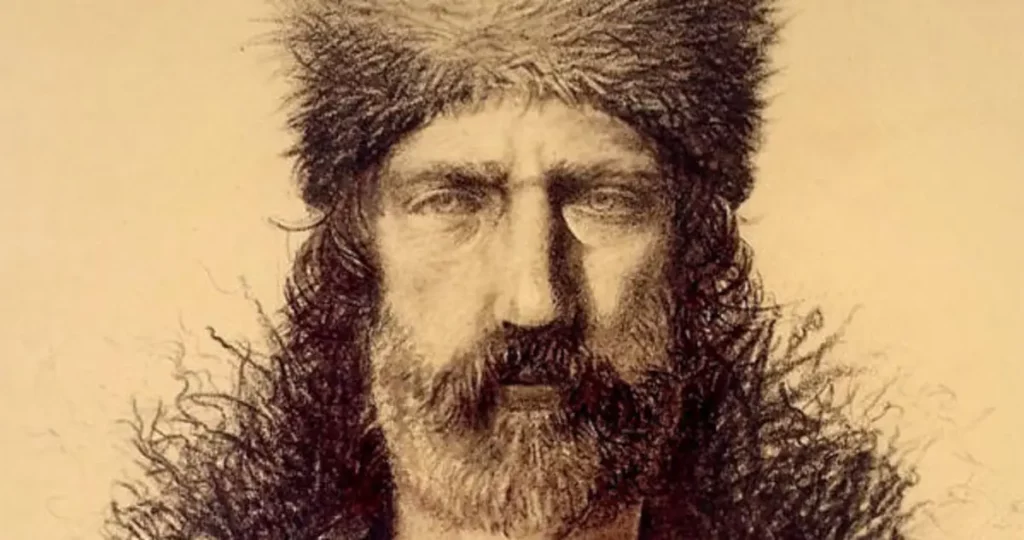

The renowned American frontiersman and fur trapper, Hugh Glass, is widely recognized as an emblematic figure of the American frontier era and a beloved folk hero.

He gained widespread fame after enduring a brutal bear attack that left him abandoned by his fellow trappers and presumed dead.

Despite the near-fatal injuries, Glass summoned the courage and strength to crawl hundreds of miles until he finally found a place of refuge and safety.

Easily the most famous depiction of his life is the hit film “The Revenant,” starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Glass, which exposed millions to his riveting tale.

Although the movie takes some liberties in its retelling, the story and character of Hugh Glass remain as captivating as ever – a truly epic journey demonstrating the ultimate will of the human spirit.

The early life of Hugh Glass

Not much is known of Hugh Glass’s early life. He is believed to have been born and raised in Pennsylvania around 1783, although no records of his upbringing remain.

The only detail of his childhood is that his parents were of Irish ancestry.

As a young adult, Glass’ extraordinary life begins with intriguing tales of piracy. According to different accounts, around 1816, he was seized by pirates led by the French pirate and Gulf of Mexico leader Jean Lafitte off the coast of Texas.

He was coerced into joining them as a pirate for almost two years. It’s claimed that Glass eventually escaped by swimming to land near modern-day Galveston, in Texas.

With piracy behind him, rumors say that the Pawnee tribe caught Glass after hiking inland and that he lived with them for a handful of years. This likely included taking a Native American wife, learning to survive off the land, and even engaging in warfare with his new tribe.

Whether or not these rumors were true, it’s clear that all of these experiences and lessons would have served him well in what was to come.

Mountain men

During the early 19th century, the American West was a place of exploration and survival.

Hugh Glass would soon join many young men, all unique in their daring and curiosity, who chose to leave their homes and participate in the first commercial enterprises of the American West.

Frontiersmen in every sense, these rugged individuals would come to be known as ‘mountain men.’

The mountain men were skilled in living in the West in the 1820s. They learned to communicate with Native Americans and recognize friends and foes.

They survived over a thousand miles beyond the settlements with just limited supplies, a rifle, and a few tools, traveling distances that dwarfed the frontiers of their grandparents’ time.

Mountain men were remarkable individuals who lived difficult but exciting lives at the edge of the country.

However, unglamorous as it was, they were known for their participation in the beaver fur trade, which at the time was dominated by William Ashley and Andrew Henry.

In 1822, the Henry-Ashley partnership posted an advertisement in St Louis newspapers seeking “enterprising young men” to ascend the Missouri river as hunters. Many men responded to the call – and Hugh Glass was one of them.

Glass joins General Ashley’s expedition

General Ashley eventually got his corps of 100 men for his fur-trading venture to “ascend the river Missouri.”

Many who responded, including famous mountain men such as William Sublette, Jim Bridger, Thomas Fitzpatrick, James Clyman, and Jedediah Smith, would later be known as “Ashley’s Hundred.”

At the outset, Ashley and Henry established Fort Henry in 1822 at the Yellowstone River and Missouri River meeting point after making the keelboat voyage upriver.

Ashley returned to St Louis in 1823 to lead a resupply trip and hire new workers, including Hugh Glass.

In March of 1823, Glass would join the expedition and head northward to Fort Henry, beginning a journey that would one day make him something of a myth, a legend, among the mountain men themselves.

Battling the Arikara

Straightaway, Glass found himself in grave danger. On their voyage up the Missouri River, General Ashley brought the party to a stop to trade for more horses that would be needed once they reached the fort.

Two Arikara villages – the local Native American tribe – dominated that particular bend in the Missouri River and were home to around 2,500 people, with earth lodges inside an enclosure of logs and dirt that made an effective barricade.

Ashley anchored his keelboats midstream from the villages, then went ashore to negotiate. Ashley had guns and ammunition, the Arikaras had horses, and the two parties traded amicably.

Ashley traded 25 muskets plus ammunition for 19 horses. However, the trading ended abruptly the moment Ashley announced there were no more weapons to trade.

Before dawn, an Arikara warned the general that some of the village warriors planned to attack the American frontiersmen, and a battle ensued.

During the conflict, Glass was shot in the leg – seriously wounded, he retreated down the river and sent for help. Fortunately, he would live to see another day.

Glass recovered and rejoined the expedition, heading overland into the Rockies. The Arikara battle would prove to be far from his last near-death experience as a mountaineer.

Grizzly bear attack & left for dead

The Missouri River was no longer deemed a viable route to the Rockies due to the costs incurred by the conflict. As such, the expedition split into two groups led by Jedediah Smith and Andrew Henry.

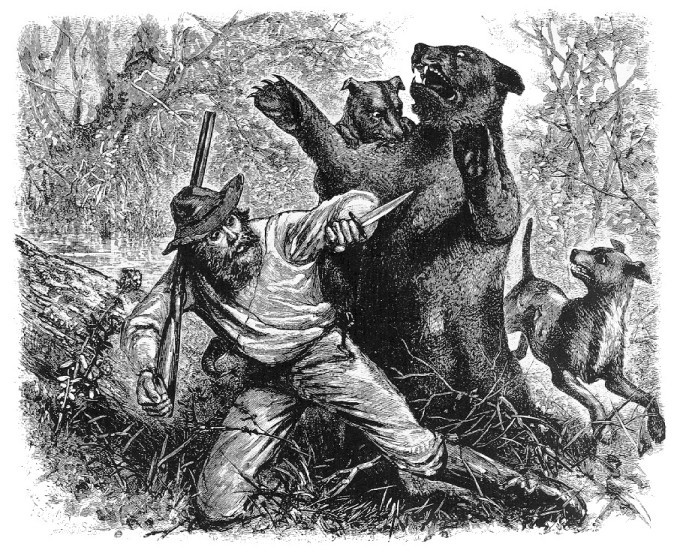

Henry’s group traveled afoot. In August or September, while scouting for game ahead of the main group, Hugh Glass encountered a mother grizzly bear with her two cubs. The protective mother bear charged and mauled him severely.

Quickly, other members caught up and killed the bear, saving Glass. With tribes in the area, Henry determined that the best approach was to stay on the move.

Thus, he ordered two men to remain with Glass. His wounds were so severe, including a broken leg, a ripped scalp, and a punctured throat, it was believed that he had just a few days left to live.

They would give him a proper burial and then travel to the fort to catch up with the main group again.

Experienced mountaineer John Fitzgerald and a younger man, 19-year-old James Bridger, who was on his first venture, agreed to the task.

After five days, Henry and the rest of the brigade departed, leaving Glass in the care of Fitzgerald and Bridger. Fitzgerald was convinced that they were in imminent danger of discovery by Indians and convinced Bridger to abandon Glass, setting his pallet next to a stream and taking his gun and other belongings.

Astoundingly, Glass survived. Driven by pure will, Glass regained some of his strength and crawled back towards the Missouri River to survive and seek revenge on the two men who left him behind.

Revenge and pursuit of Bridger and Fitzgerald

The story of Hugh Glass is one of incredible resilience and revenge. After being left for dead by Bridger, Glass found himself alone and unarmed in hostile Indian territory with a broken leg, festering wounds, and barely any means of survival.

Crawling towards the nearest help, 200 miles away, Glass survived for months on wild berries and roots and even raw meat from a downed bison calf. He was driven by revenge, fueled by the thought of killing the men who left him for dead.

It took Glass two months to crawl to the Cheyenne River, where he built a raft and allowed the current to carry him downstream to the safety of Fort Kiowa. Once he regained his health, he set out to find the two men who abandoned him.

Upon reaching Fort Henry, he found it deserted – the group had moved to a camp not far away. The trappers he met there – his former expedition members, especially – were stupefied to see the man they believed to be long dead.

There, Glass found the young man, Bridger, but, in time, forgave him due to his youth and then re-enlisted with Ashley’s company.

Fitzgerald became the object of his revenge

Meanwhile, Fitzgerald had returned to the expedition only to leave and enlist in the army. Glass followed his trail to Fort Atkinson, not too far away.

Here, the story varies. Some say Glass had mercy on him, warning him never to leave the army or he would still kill him. Other accounts report that he was never left alone with Fitzgerald for fear of what he would do to him.

After everything that had transpired, Fitzgerald lived and Glass reportedly obtained $300 as compensation. In the end, Hugh Glass moved on, reestablishing himself elsewhere, marking the end to a saga of legendary measure.

Later life and death of Hugh Glass

Years later, in 1833, Glass was shot and killed during a skirmish with hostile Arikara warriors upon his return to the Upper Missouri.

Despite his quiet demeanor, the account of his incredible journey spread throughout the frontier, retold by scores of mountain men and even some native American tribes.

Although Glass’ story required no embellishment, many false versions emerged over the years. It’s hard to entirely sort the fact from the fiction, but the foundational story remains.

The account of Hugh Glass’ survival after being attacked by a grizzly bear and left for dead in the middle of the wilderness has become not only a fundamental part of the history of the Rocky Mountain fur trade but also a gripping tale of blockbuster proportions known all over the world today.

Sources

“Hugh Glass – Fact vs Fiction – the True Story of Hugh Glass.” The Real Story of Hugh Glass, Sublette County Historical Society, 7 June 2016, http://hughglass.org/

“Hugh Glass.” American History, 16 Aug. 2019, https://american-history.net/19th-century-america/westward-expansion/hugh-glass/

“Hugh Glass.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 6 Feb. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hugh-Glass

Legend of Hugh Glass – San Juan Unified School District. https://www.sanjuan.edu/cms/lib/CA01902727/Centricity/Domain/4026/Hugh%20Glass.pdf.