As a child, were you ever afraid of going to the dentist? For most, that fear is largely irrational.

But in Sweden beginning in the mid-1940s, the children of the Vipeholm mental institution were subjected to a dental experiment that was truly a nightmare.

At the end of the years-long study, many of the patients had teeth that were so rotten they had turned completely black. What’s worse is that the participants had no choice in the matter. The researchers showed very little regard for the children they studied.

Some were even looked at like they were barely more intelligent than vegetables. As a result, the experiment ruined teeth, caused excruciating pain in the subjects, and left a dark legacy that has been difficult to rectify.

Mental Disease in the Early 20th Century

When we look back at some of the experiments that were performed back in the first half of the 20th century, they may seem shockingly unethical. And that is especially true when it comes to people with mental disabilities.

For much of history, people with mental disabilities were generally kept separate from the rest of the population rather than be given any kind of treatment. Throughout the 18th century, patients were often kept in dungeons where they were chained, abused, and neglected.

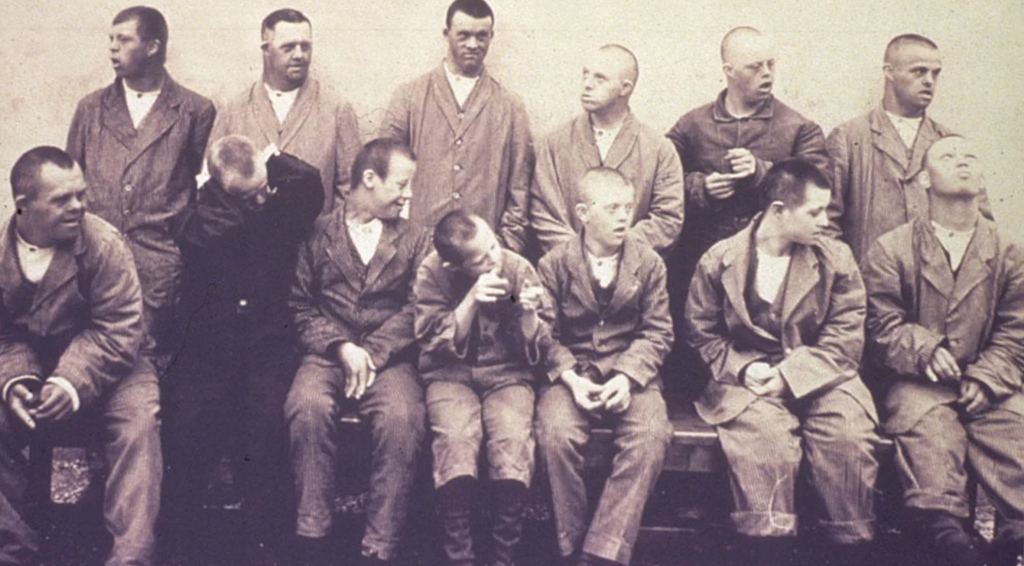

By the 20th century, mental patients were still separated from society but they were placed in asylums and watched over by nurses. Yet even then, people with mental disabilities were often seen – and treated – as less than human and given very little control over their lives.

Unfortunately, too often that lack of control led to dangerous consequences for many patients who suffered everything from electroshock therapy to ice baths to the Vipeholm experiments.

The Vipeholm Institution

The Vipeholm Institution, located just outside of Lund, Sweden, was created in 1935. It was designed to be a place to house people with “severe intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

It was a large facility. At its height, it could hold over a thousand residents. But the treatment of those residents, especially in the beginning, could be quite appalling.

As one journalist described it, the patients often went unsupervised and without any kind of organized activities. They would run through the wide halls of the facility or remain tied to their beds all day long. What’s worse, if they misbehaved they would often be submerged in an ice bath to correct their behavior.

It didn’t help that the single physician who worked at the facility had a degrading way of classifying his patients. Based on what he determined was their mental capacity, he gave them each a number one through six.

On the lowest end of the scale, those with a grade of zero were considered, “biologically lower standing than most animal species.” He didn’t see much potential in the rest of the patients on the lower half of the scale either.

Ultimately, these were the patients who became the subjects of his experiments.

The Vipeholm Experiments

In Sweden during the 1940s, researchers were trying to figure out what was causing the high rates of tooth decay among the population.

In the previous decade, one study found that up to 83 percent of children developed cavities by the age of three. With age, dental problems tended to worsen. This left many adults with gaping holes in their smiles where their teeth had to be pulled.

The Swedish government wanted to address this significant health issue. The only problem was that they didn’t know what was causing the cavities. At that point, the connection between sugar and tooth decay was not firmly established. Some doctors thought cavities were caused by disease or other dietary factors.

That’s why in 1945, the government undertook a series of experiments to test the connection between sugar and tooth decay. Since the residents in Vipeholm were considered to be of low intelligence and highly compliant, the researchers decided it would make for the perfect location to carry out the experiments.

For the first two years, the subjects were given a low-starch diet that included supplements of vitamins A, C, and D, and fluoride tablets. During this period, they were not allowed to snack between meals, and their dental health was monitored closely. At the end of these two years, 78% of the participants hadn’t developed any new cavities.

Then they commenced the second phase, and this is where things took a turn for the worse.

During this second two-year phase, the researchers added sugar to the diets. But they added twice what the average Swede consumed at the time. The children were further divided into three separate groups, each with a different method of sugar consumption.

The first group was given sticky bread (think cinnamon buns) with their meals. But this was sticky bread with added sugar.

The second group took in their sugar by drinking it. They were given beverages that had 1 ½ cups of sugar added to them.

The third group was told to eat sticky candy, such as chocolate, toffee, and caramels between each of their meals. These children ate anywhere from 8 to 24 pieces of candy in each sitting!

So, how did each group fare?

It turns out that the first two groups didn’t experience very significant adverse effects. But the third group – that is, the one that was given sticky candy after meals – did suffer.

The candy had, as expected, stuck to their teeth and ruined them. Their teeth were rotten and had even turned black in some cases. The researchers repaired the damaged teeth of many of the children. However, this usually meant pulling them out.

When it came to some of the lower-functioning children, however, they didn’t even receive this option. These patients were simply left to suffer with the terrible pain of rotten teeth.

The Legacy of the Vipeholm Experiments

In 1964 the international community approved the Helsinki Declaration. This document provided a non-binding framework for proper ethical human experimentation.

But the Vipeholm experiment took place at a time when there was no international consensus on how best to approach ethical questions in experimentation.

One of the researchers who participated in the Vipeholm experiments admitted that “we dentists didn’t see any ethical problems with the study itself.” They were mostly focused on the outcomes of the experiments.

And those outcomes had long-term effects on how we think about dental health.

For one thing, the experiment showed that there was indeed a connection between sugar intake and dental decay. They showed that the connection was specifically linked to sugar that ends up adhering to the teeth. This was demonstrated in the results of the three different groups.

The findings of the study also led to the development of artificial sweeteners. Within Sweden, the government embarked on a nationwide sugar reduction campaign to educate children to lower their sugar intake.

It soon became a popular tradition to eat “all the sweets you like, but only once a week.” That initiative greatly improved the health of a generation of Swedes. Now, eating Saturday sweets still remains an important part of Swedish culture.

The history of the Vipeholm experiments also touches on the thorny issue of medical ethics and patient consent. Throughout history, experimental subjects have been forced into all kinds of abuse in the name of scientific progress.

Unfortunately, the Vipeholm experiments were far from the first questionable studies done against people’s will.

From 1941 to 1943, it was reported that 200 mentally ill patients were starved to death in Vipeholm. Elsewhere in Sweden, many homosexuals were lobotomized against their will in those years. Homosexuality was considered a mental disorder and lobotomies were thought to be an appropriate treatment.

Around the same time In the United States, researchers were testing radioactive substances on human subjects as part of a project to develop an atomic bomb.

The most heinous of all of the so-called experiments of the war years were, unsurprisingly, carried out by Josef Mengele and his ilk in Nazi concentration camps during World War II. From sewing twins together to removing body parts, these experiments were so dark they don’t even count as science.

But it was largely the response to these wildly unethical experiments that new standards for conducting research were finally developed. If there’s a silver lining to the Vipeholm experiments, it’s that we’re still benefiting from the safeguards that have been put in place as a reaction to these kinds of studies.