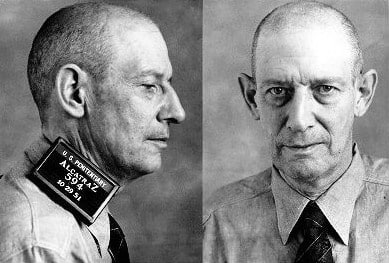

Brought to public awareness primarily by the 1962 American biographical film, Birdman of Alcatraz (starring Burt Lancaster), Robert Stroud was a convicted murderer. He was sent to federal prison where he spent 42 years in solitary confinement.

Yet incredibly, he developed such an obsession with birds that he became one of the foremost authorities on canaries in the world.

(It should be noted that while Stroud did serve time in Alcatraz, it was actually while incarcerated at Leavenworth Penitentiary, Kansas, that the “bird” phase of his story takes place.)

Childhood

Robert Franklin Stroud was born on January 28, 1890, in Seattle, Washington. He was the eldest child of Benjamin Franklin Stroud and Elizabeth Jane (née McCartney), a divorcee with two daughters from a previous marriage. The Strouds had a second son, born two years after Robert.

Stroud’s father was an alcoholic who abused his wife and children. He drove his eldest son to turn to the streets at an early age. Stroud quit school after the third grade and ran away from home at the age of 13.

Early Life

At age 18, Stroud made his way to the Alaska Territory to work on a railroad construction gang. But he soon began a relationship with an older prostitute and dance-hall entertainer named Kitty O’Brien.

Stroud and O’Brien, hoping for a better life, moved to Juneau, Alaska. Which was at that time, a booming gold town. This is where the event occurred that would forever change his life.

While the details of the story are unclear, it seems that a bartender named Charlie Van Dahmer (Damer) had been one of O’Brien’s regular customers. But on this occasion, not only did Van Dahmer refuse to pay O’Brien for her services, he beat her.

Unwilling to let the incident go, Stroud shot and killed the man. He then took his wallet to ensure that he and O’Brien were compensated.

Believing himself in the right, Stroud surrendered to the local marshal, who promptly arrested him. Subsequently found guilty of manslaughter, on August 23, 1909, Stroud was sentenced to 12 years in federal prison.

Incarceration

Stroud was sent to McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary in Washington State. He proved to be a difficult inmate.

He assaulted a hospital orderly on one occasion (who he insisted had reported him to the administration for attempting to procure morphine through intimidation and threats). And he stabbed a fellow inmate on another occasion (who, reportedly, squealed on him for stealing food).

In 1912, three years into his sentence, Stroud was transferred to Leavenworth Federal Prison in Kansas.

He displayed a surprising aptitude for learning at this new facility. He took Kansas State Agricultural College extension courses in mechanical drawing, engineering, hard science, theology, and mathematics.

But his violent tendencies surfaced in 1916. He stabbed a guard to death in the prison mess hall with a butcher’s knife in front of 1100 inmates after turning away his brother who’d attempted to visit him for the first time.

He was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death by hanging. It was a bedridden President Woodrow Wilson, who in 1920 commuted his sentence to life in prison without parole by Executive Order. Stroud’s mother Elizabeth met with the President’s wife, Edith, and begged her for leniency.

To prevent Stroud from further violence, warden T.W. Morgan sentenced Stroud to serve his life sentence in solitary confinement. The decision to isolate him was to have very unexpected consequences.

The “Birdman” is Born

In 1920, while in solitary confinement at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary, Stroud discovered a sparrow nest in the prison yard. It was brought down from a tree during a storm and had three live hatchlings inside. Seemingly out of character, Stroud took the birds back to his cell and raised them to adulthood, sparking what would become a longtime fascination with birds.

He requested–and was granted–permission to raise canaries. And within a few years, Stroud had accumulated a collection of some 300 canaries he kept in hand-crafted cages made from cigar boxes.

First in his cell, then in an adjoining cell, he was permitted to use. The “Birdman’s” aviary became one of the prison’s main attractions for visitors.

Stroud also built a makeshift laboratory to develop homemade curatives for his birds suffering various ailments. He read every book in the prison library pertaining to birds, bird breeding, and bird ailments.

He kept detailed records of his observations regarding behavior and illnesses that the books failed to cover. He also began a nationwide correspondence with other breeders and bird experts to expand his knowledge.

Within a few years, Stroud had established a lucrative mail-order business to sell his birds and natural curatives. He quickly became known as a bird authority. His business would continue to thrive until 1931 when a new prison system-wide mandate prohibited it.

Fame From the Inside

After successfully finding a way to smuggle a 60,000-word manuscript titled Diseases of Canaries out of the prison, Stroud’s book was published in 1933—establishing him as an unqualified expert.

In subsequent years he made important contributions to avian pathology. Most notably a cure for the hemorrhagic septicemia family of diseases. This gained him respect among ornithologists and everyday people (particularly chicken farmers).

Stroud’s continued research led to the publication of a second book, Stroud’s Digest on the Diseases of Birds, in 1943. Filled with detailed, artfully drawn illustrations he drew himself (including internal organs), his Digest came to be considered one of ornithology’s finest authoritative works.

Stroud’s successful mail-order business irked the warden. But it was the discovery that he was secretly making and consuming homemade grain alcohol in his makeshift lab that effectively ended his life with canaries; and his time at Leavenworth.

In 1942, Stroud was transferred to Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary. This was a maximum security prison on Alcatraz Island, 1.25 miles off the coast of San Francisco, California.

Alcatraz

On December 19, 1942, the 52-year-old Stroud began serving a 17-year term at Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary. He was initially told that he may be permitted to resume raising his birds.

But in 1943, he was assessed by psychiatrist Romney M. Ritchey who deemed him a dangerous psychopath. He advised the warden that Stroud should not be allowed to keep birds. This, however, did not deter Stroud from continuing his ongoing research.

Though still serving his time in isolation, Stroud continued writing, producing manuscripts (one on the history of the U.S. Penal System). He also wrote an autobiography–though he was denied permission to publish any of them.

“The Battle of Alcatraz”

Considering Stroud’s infamous volatile personality, in May of 1946, the 56-year-old Stroud did something that seemed quite out of character. He took it upon himself to protect a group of inmates in “D” Block caught up in a riot.

During this, prison guards were firing rifles into the block to subdue the rioters. Henceforth known as “The Battle of Alcatraz,” Stroud climbed over the third-tier railing and lowered himself to the second-tier. He then dropped onto the “D” Block floor—amidst the incoming fire.

In a courageous attempt to protect the inmates who were not part of the uprising, Stroud closed the steel doors to the six isolation cells. He yelled out to the Warden that there were no firearms in “D” Block and that those who’d instigated the riot had retreated to another section of the prison.

He implored the warden to consider the many innocent lives that would be lost if the guards continued firing arbitrarily.

The “Birdman” of Hollywood

In 1946, Stroud—having developed a talent for making the best of a bad situation—shopped a manuscript he’d written around to Hollywood filmmakers of his life story. It was a memoir tentatively titled, Rehabilitation.

Alcatraz warden James Johnston reported to the director of the newly-instituted Federal Bureau of Prisons, James V. Bennett, that Stroud expected Hollywood to pay $50,000 for his life story. Bennett is quoted as saying that he would “give up his position and immediately move to Hollywood” if any studio were foolish enough to pay the fee Stroud was asking.

It is unclear how his story found its way to LA probation-officer-turned-non-fiction-book-writer Thomas E. Gaddis. But in 1955, Stroud became the subject of Gaddis’ acclaimed biography, Birdman of Alcatraz.

Although the account details Stroud’s propensity for violence, it also paints him as a man fighting to maintain dignity within extremely difficult circumstances.

With the success of the book (and growing fascination with “The Birdman”), Twentieth-Century Fox optioned the book. They hired screenwriter Guy Trosperm (The Pride of St. Louis, Jailhouse Rock) to adapt it to the big screen.

But when Federal Bureau of Prisons director Bennett heard about the project, he vehemently objected to the “glamorizing of criminals.” He told Fox he absolutely did not want the film to be made.

Rather than face legal reprisal, Fox withdrew from the project. Gaddis attempted to meet with Bennett to discuss his concerns but was unsuccessful.

After substantive changes were made to the script, the project was picked up by United Artists Studios. The result, however, is a film based on Gaddis’ biography. It was partly truth, partly fiction, downplaying the abuse Stroud suffered in prison.

Final Years

In 1959, Stroud was transferred to the Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri. This is where he spent the last four years of his life; with considerably more freedom.

Despite the increased attention garnered by the book and film, and his model-prisoner status, Stroud remained unsuccessful in his attempts to attain parole.

Stroud was never permitted to see the film (in which Burt Lancaster portrayed him as a mild-mannered and humane individual). But “Birdman of Alcatraz” earned Lancaster an Academy Award nomination for best actor. The film received a total of four Academy Award nominations.

In 1963, shortly before his death, Stroud met with Lancaster. Lancaster subsequently petitioned for Stroud’s release but failed. In retaliation, Lancaster did what he could to expose Bennett’s efforts to censor the film, offering it as evidence of a personal vendetta against Stroud.

Stroud filed a lawsuit to have his manuscripts released. The decision was still pending when he was found dead in his cell, from natural causes, on November 21, 1963.

In Absentia

After his death, there was a growing fascination with Stroud’s unusual life and accomplishments. It resulted in a number of projects to further illuminate the (in)famous murderer-turned-ornithologist.

Actor Art Carney played Stroud in the 1980 made-for-TV movie, “Alcatraz: The Whole Shocking Story.” Dennis Farina played Stroud in the 1987 TV movie, “Six Against the Rock,” a dramatization of the “Battle of Alcatraz” that took place in 1946.

In music, Stroud was the subject of progressive rock band Yes’ keyboardist’s instrumental “Birdman of Alcatraz” on his 1977 Criminal Record, a concept album about criminality. Also, Stroud is the subject of the song “The Birdman” by Canadian Rock band Our Lady Peace.

Additionally, several video games including Galerians and Team Fortress 2 pay homage to him.

A Voice From the Grave

In recent years, new research has shown that the Federal Bureau of Prisons collaborated with Hollywood’s censorship body, the Production Code Administration, for many years. And that Birdman was in fact the culmination of a decades-long struggle to control all films about Alcatraz, to hide the atrocities that took place there.

In February of 2014, after the statute of limitations expired, Stroud’s book, Looking Outward, A Voice From the Grave was finally published in eBook form. Among other details, the book reveals Stroud’s homosexuality and the rampant corruption among prison guards and wardens at Alcatraz.

With the movie rights already sold and the promise of additional volumes soon available, it seems likely the “Birdman’s” story will remain a continued source of fascination in the public’s imagination.

References

History.com., “Robert Stroud,” Robert Stroud – Birdman, Crimes & Death (biography.com)

BioGraphics.org., “Robert Stroud—the Birdman of Alcatraz,” Robert Stroud – The Birdman of Alcatraz – Biographies by Biographics

Biography.com., “Robert Stroud,” Robert Stroud – Birdman, Crimes & Death (biography.com)

Jstor.org., “Bennett, Breen, and The Birdman of Alcatraz, a Case Study,” https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/filmhistory.28.2.02

Alcatrazhistory.com., “Robert, ‘the Birdman of Alcatraz’ Stroud,” Robert Stroud – The Birdman of Alcatraz (alcatrazhistory.com)