Last updated on November 21st, 2023 at 02:14 am

One of the most well-known faces in the fast-food industry, Colonel Sanders pioneered fried chicken to glory, not just in America but worldwide.

He has been synonymous with KFC since the brand became a crash hit. An iconic businessman, if there ever was, Colonel Sanders lived a life not many would survive, only to turn it on its head at the very end.

A Rough Start

Born in 1890, Colonel Sanders, a.k.a. Harland David Sanders, had humble beginnings in Henryville, Indiana.

He had a rough start in life. He lost his father, Wilbert Sanders when he was only five. His mother was left almost penniless after Wilbert’s death, so she spent long hours toiling at a local tomato canning factory and sewing for her neighbors.

Working two jobs meant she’d often be away from home for long periods. In her absence, Harland, the oldest of three siblings, had to step into her shoes.

Around this time, he taught himself to cook, picking up skills that would later make him famous.

Harland scored his first job working on a local farm when he was ten. By the time he was 12, his mother had remarried, and they shifted base to live with their stepfather in the suburbs outside of Indianapolis.

But he did not see eye to eye with his new father, and within a year, he was sent away to Clark County, back to where his family came from.

However, the enterprising Harland soon found a job at a farm in Greenwood, Indiana. He made $10 to $15 a month and had a room. But balancing his work with school proved to be a chore for him, so he dropped out after sixth grade.

A Stint in the Army

When Harland was 16, he falsified his birth certificate to meet the minimum age requirement for enrolling in the US Army and joined.

But while many assume that Harland earned his rank of “Colonel” after years of service, that is only partially true. After only a brief stint in Cuba, he was honorably discharged from service. He was given his title much later, but more on that later.

From One Failure to Another

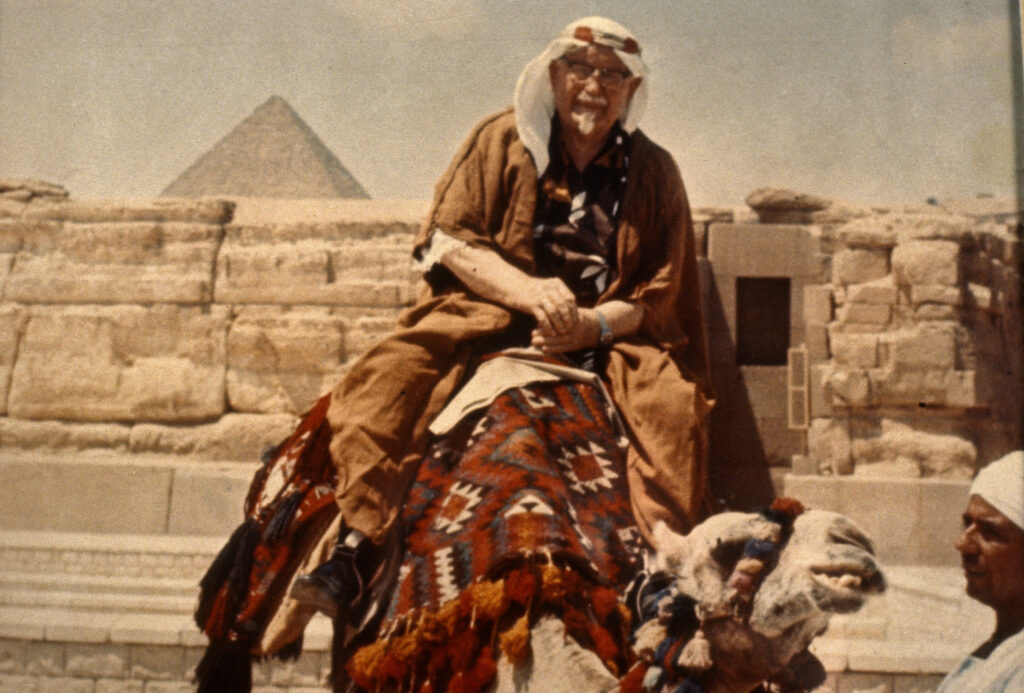

Nonetheless, Harland led a rather eventful life. He donned the hat of a streetcar conductor, a railroad firefighter, an insurance salesman, a secretary, a Michelin tire salesman, a motel operator, and a ferry boat operator. He even started a ferry business on the Ohio River, but that lasted only a short time.

His life seemed to be one of tragedy. He hurtled himself from business to business, facing failure at every step.

Even his stint in the Justice of the Peace Court in Arkansas came to an abrupt end when he was accused of physically abusing his own client.

Later, in 1927, Harland ran a Standard Oil gas station in Nicholasville, Kentucky. But he had to shut down the business due to the Great Depression and the following drought. He then lost $38,000 trying to open an airport in Corbin.

Tragic Family Life

His bad luck at jobs also seemed to follow Harland into his family life. His wife, Josephine King, was not pleased with his inability to be at a job. She ended up abandoning him for a short time, taking the children with her.

Later, he lost his son Harland Jr. who was only 20, to a routine tonsillectomy procedure. The loss of his son caused Harland to sink into depression.

The tragedy was the final nail in the coffin of his marriage and family life. In 1947, they divorced each other after 40 years of being together.

Two years later, Harland married Claudia Leddington, with whom he remained with until his passing in 1980.

Food for the Soul

In 1930, Harland took another shot at business and started a gas station in Corbin with a bit of help from Shell. He would cook and cater to all those who visited the gas station, earning a few extra bucks.

But all wasn’t hunky-dory. Soon trouble started brewing between him and his rival gas station owner Matt Stewart. The disagreement led to both firing shots, where Matt fatally shot a Shell manager. This bloody affair left everyone stunned.

A few years after this incident, Harland removed the gas pumps and set up his first full-fledged restaurant.

The First Taste of Success

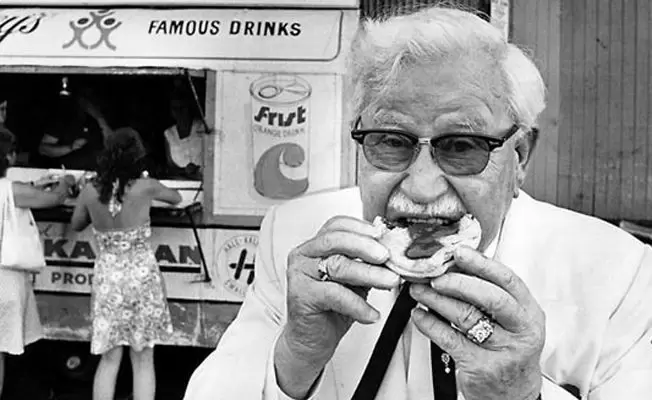

During this time, Harland was working on perfecting his famous chicken recipe. Then, in 1939, he struck gold. He found a method of pressure cooking the chicken that would cut down on his cooking time and make an even more delicious dish than before.

His restaurant business saw the face of continued success, and his winning streak grew hotter by the day. However, not surprisingly, things were about to take a turn for the worse.

Back to Square One

In the 1950s, two blows of bad luck struck Harland rapidly and put his newfound success at risk. The first blow hit when the highway junction in front of his restaurant was relocated.

This ended the heavy traffic that regularly passed by and provided him with a steady flow of customers.

This development would have been enough to put a massive dent in his restaurant business. But then came the announcement of a new interstate highway. It was to be built on a location that bypassed Harland’s restaurant by seven miles.

In 1956, realizing that his restaurant was about to be left in the dirt, Harland auctioned off the site of his restaurant, taking a loss on the sale. He had no income to support him. So he was forced to scrape by on his savings, the auction proceeds, and his monthly Social Security check of $105.

After a brief taste of success, Harland had to start from scratch again.

Colonel Sanders

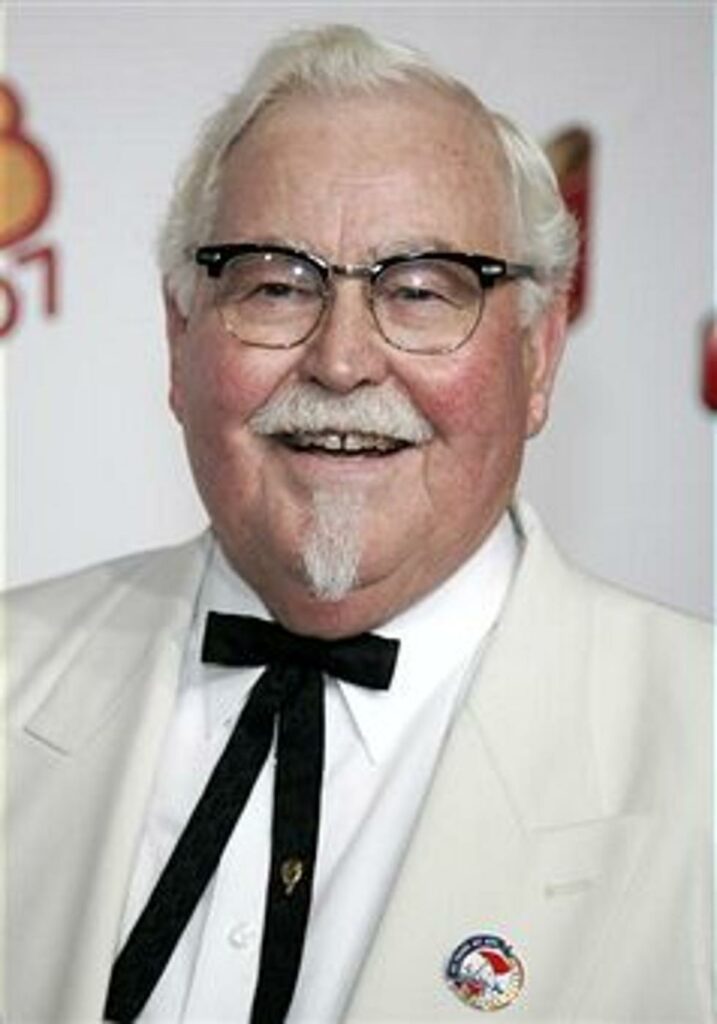

In 1950, Kentucky governor Ruby Laffoon awarded him the highest rank that a state could bestow: that of a Colonel.

This incident had a major impact on Harland’s sartorial choices. He began to wear a black suit coat and string tie, like Colonels from the south would. He switched to an all-white suit when he found out his antics in the kitchen would often soil his black suit with specks of flour.

Life on the Road

Enterprising and ever hopeful as Harland was, he decided to sell his secret recipe to franchisee restaurants in return for a small fee. He demanded 4 cents for every chicken they sold using his recipe.

Pete Harman, his friend from Salt Lake City, was the first one to take Harland up on the offer. Pete’s sales went through the roof since he began to serve chicken made with his friend’s special recipe.

But life was still not easy for Harland. First, he had to always stay on the lookout for suitable franchisee restaurants.

Then, if he came upon one, he would have to convince the restaurant owner to allow him to cook some chicken for the restaurant’s employees.

If they enjoyed this new recipe, he would then cook for the restaurant’s customers for a few days. After that, it was only if they, too, approved that the restaurant would enter into negotiations to start franchising for Harland.

This arduous and, at times, humiliating process was tiring him out. He still had no money and would live out of his car, surviving on meals thrifted from his friends.

Finger-Lickin’ Good

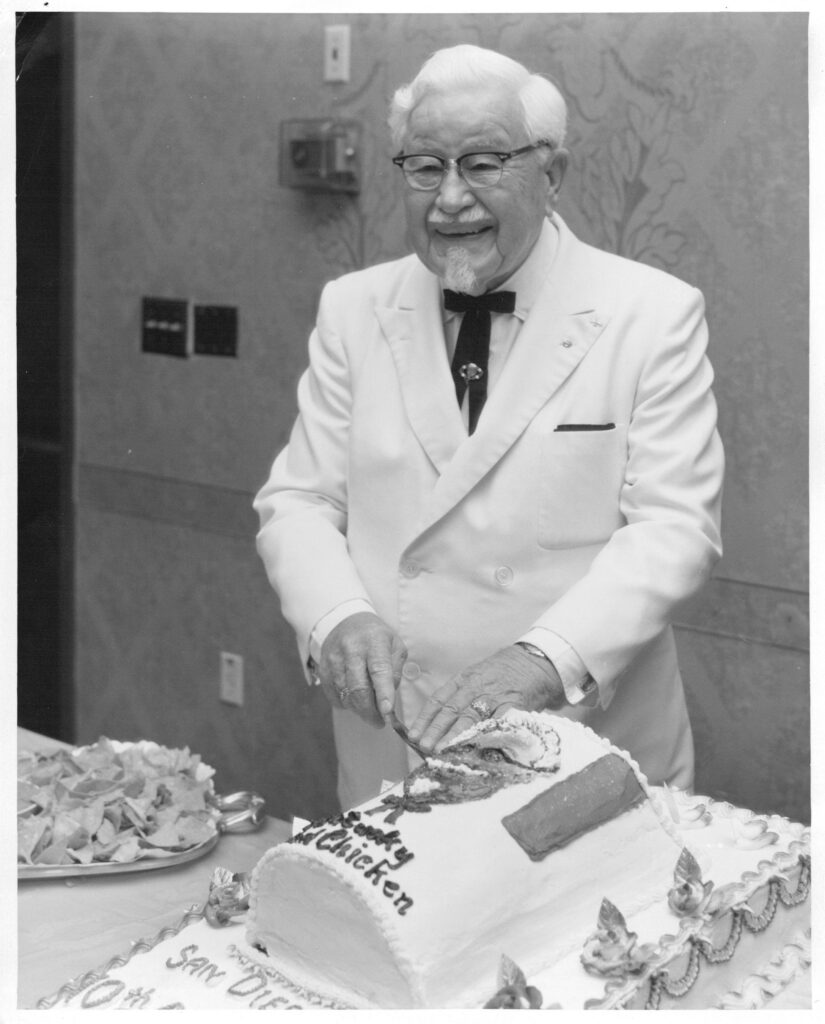

Nonetheless, the business tactic worked. By 1964, Harland had franchised more than 600 outlets and built a multi-million-dollar business. These restaurants sold chicken made using his recipe, but there was no KFC in place.

During this time, a pair of sharp-eyed young lawyers named John Y. Brown, Jr. and Jack Massey noticed his stellar growth. So they started pressuring the colonel, who was now aging, to sell his company.

Despite Harland firmly refusing several times, they wore him down in the end. They swore that they would never tamper with his chicken recipe and would ensure the highest level of quality control for Kentucky Fried Chicken.

Eventually, Harland sold his company for $2 million. But he had one condition: the new owners should keep his recipes intact as promised.

The new owners widely used his face for publicity and soon sold Kentucky Fried Chicken to Heublein Inc. Heublein moved the company’s headquarters to Tennessee, started charging a franchise fee, and also took a percentage of sales instead of Harland’s preferred rate of a nickel per chicken.

They even began to use their own recipes instead of his original recipe.

Seeing his brainchild company’s food quality decline, Harland sued the company for $112 million for not keeping the one promise that they had made.

They settled the case out of court, and Harland reportedly received $1 million. He also took a more hands-on role at the company and taught its cooks the right methods for preparing his recipes.

The Man and his Legacy

At the age of 90, Harland succumbed to pneumonia. At that time, there were around 6,000 KFC restaurants in more than 48 countries. Today, there are more than 25,000 KFC locations in 145 countries. As long as fried chicken woos foodies across the globe, his legacy will live on.

This was a very interesting story how he came up down in the middle all round to a great success Kentucky Fried Chicken is the best thank you for that story I really appreciate what are some cycle picks us up really who wouldn’t want to wear this skin

That final sentence – do you mean ‘woos’ instead of ‘woes’? They have very different meanings! 🙂

Thanks for the correction!

Kind of interesting that you didn’t mention he lived in a suburb of Toronto (1335 Melton Drive, Mississauga) for the last 15 years of his life