Australia is known for a lot of things. Dangerous spiders and venomous snakes among all sorts of other exciting wildlife. Beautiful cities like Sydney, and the inhospitable expanse of the outback are just a few examples.

But there is something dark in the maritime history of Australia. It is something so disturbing that it is considered one of the worst shipwreck-related incidents of all time.

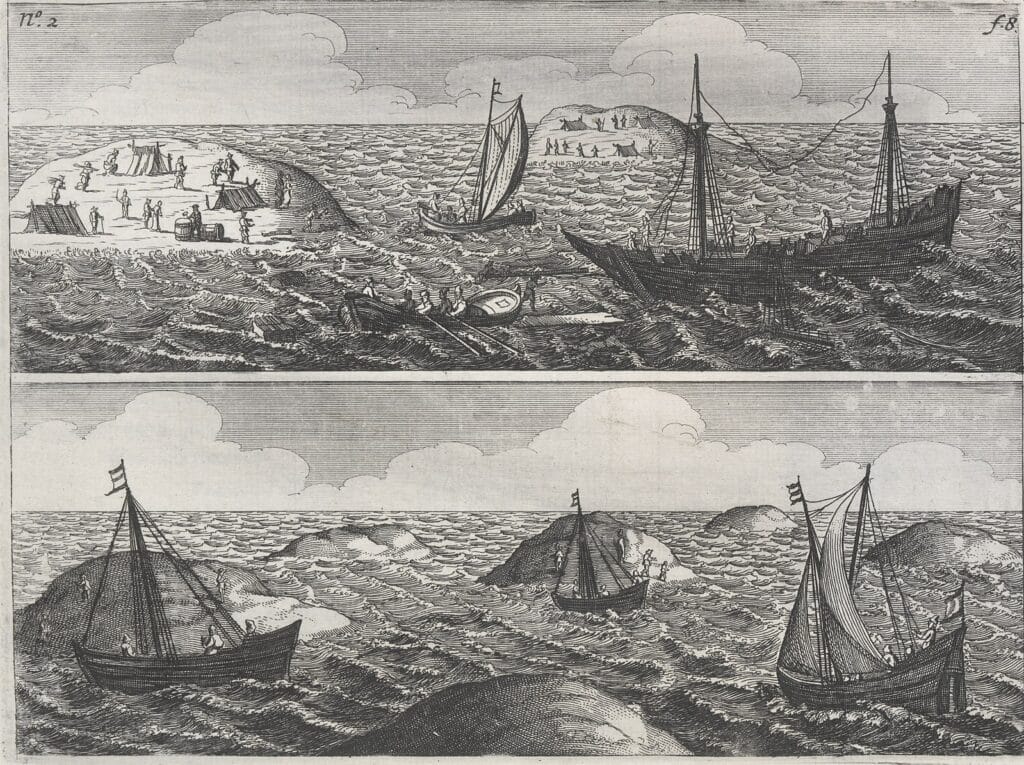

In the 17th century, a ship called the Batavia was sailing off the Western coast of Australia when it wrecked. This forced all aboard to have to swim to safety. Not all of them made it, but the wreck was only the beginning of the terrors that would plague the former crew of the Batavia.

It wouldn’t be the elements that tormented them. Instead, it would be one of their own that made the coming weeks a living hell.

Batavia, Ship of the Dutch East India Company, and Her Crew

Like most ships built by the Dutch East India Company (VOC), the Batavia was a formidable vessel. Had it not been wrecked it would have spent its life ferrying spices from the Dutch East Indies back to the Netherlands.

It was complete and ready for its maiden voyage in October of 1628. But first, it needed a crew.

Command of the Batavia was given to Francisco Pelsaert, a senior merchant with the VOC. His skipper would be Ariaen Jacobsz, a man who was already known to Pelsaert, but not in a positive way.

Pelsaert and Jacobsz had a run in some time before they were both assigned to Batavia, where an intoxicated Jacobsz received a public dressing down by Pelsaert. Already the crew was not off to the best start.

The last piece of the puzzle that would lead to the horrifying circumstances after the Batavia wreck was a junior merchant named Jeronimus Cornelisz. Cornelisz had suffered the terrible loss of his son while the infant was in the care of a wet nurse.

After a legal battle to prove that the child contracted syphilis from the said nurse and not him or his wife, Cornelisz was left bankrupt and out of options. After this, he went to Amsterdam, where he found work with the VOC and was assigned to Batavia.

All in all, the Batavia had 330 people on board–180 sailors, 100 soldiers, and the rest private travelers. With all of its crew in place, including the three main characters of this story, the Batavia was ready for its maiden voyage.

No one knew it would also be the ship’s last.

Wreck and Mutiny on the Batavia

Plans for Mutiny

During the voyage, Pelsaert took ill for a brief time, leaving Jacobsz in charge, with Cornelisz not far behind. The second-in-command and Cornelisz became fast friends, and together, they began to plan a mutiny to take Batavia for themselves.

There was a significant amount of expensive cargo aboard. With Cornelisz facing legal trouble back home, the idea of a fresh start was all too tempting for the two men.

The Batavia had been traveling with a fleet of other ships. But after they ran into a storm off the Cape of Good Hope, they became separated from the rest.

With the Batavia now on its own, Jacobsz and Cornelisz began to sow discontent among the crew. The crux of their plan was the sexual assault of a wealthy female passenger, Lucretia Jans, with the hope that Pelseart would punish the entire crew for the crime.

Unfortunately for Jacobsz and Cornelisz, Lucretia couldn’t identify her attackers, and the crew went unpunished.

The Wreck

Sailing along the coast of Australia, the Batavia struck the Morning Reef near the Houtman Abrolhos islands on June 4, 1629. Most of those aboard were able to reach the shore of Beacon Island. 40 sadly didn’t make it and drowned in the attempt.

Once everyone was on land, Pelsaert put a plan into motion. He had the survivors transferred to the nearby islands.

They all searched the reachable islands for resources, but Pelsaert soon realized that there was little to no food or water to be had. Having little other choice, Pelsaert took Jacobsz and other senior officers to the Australian mainland to find fresh water.

Still, Pelsaert fell short on finding water for the survivors. He made the difficult decision to try to make it to Batavia, the city in the Dutch East Indies that his ship had been named for. Once he reached Batavia, he was given command of a new ship, Sardam, in order to rescue his stranded people.

But while Pelsaert and Jacobsz were gone, chaos reigned on the Houtman Abrolhos Islands.

The Murders

Once alone with the rest of the survivors, Cornelisz started to plot again. This time, his scheming would be deadly.

Since he was the senior ranking member of the VOC, Cornelisz was put in control. Using a longboat from the Batavia, he transferred most of the soldiers led by Wiebbe Hayes to a nearby island under the pretense of finding food or water.

He told the soldiers to use smoke signals if they found anything, and they would be retrieved. In reality, Cornelisz was leaving the soldiers to die.

He planned to start a kingdom of his own. To do so, he needed to thin out the amount of able-bodied men who might resist.

Cornelisz already had men loyal to him from the previously planned mutiny plot. They stayed loyal when he took absolute control of the rest of the survivors. These followers were more than happy to obey his commands.

His brief reign over the survivors was bloody and brutal.

Over the following weeks, Cornelisz would order the murders of over 100 people. He started his horrific rule by having his men slaughter all the survivors that were on one of the islands.

With most of the survivors now solely on Beacon Island, Cornelisz continued to have them slaughtered for inane reasons. He never did the killing himself. Instead, he used his control over the other survivors to make sure they did the dirty work for him.

His methods of execution ranged from silent murder during the night to intentional drownings. He focused on those who refused to obey, as well as the sick and weaker survivors. But murder wasn’t the only atrocity he committed.

Some of Cornelisz’s men took sex slaves, raping any female passengers they chose. Cornelisz himself took Lucretia Jans, the woman he had previously assaulted, as his private sex slave.

By the time rescue finally arrived, Cornelisz would have murdered 110 people. Only 70 survivors were left.

The Rescue

Unbeknownst to Cornelisz, the men that he had left to die on the neighboring island, now known as West Wallabi Island, had actually found food and water.

They signaled Cornelisz on Beacon Island, but it didn’t take long for them to realize something was very wrong. The survivors on West Wallabi fashioned weapons and built a small fort. They readied themselves to face Cornelisz and his men.

When Cornelisz sent his men over to West Wallabi to take control of the water source, they were met with well-fed and well-hydrated soldiers and quickly defeated. Cornelisz was taken hostage, leaving his men to reform under another man named Wouter Loos.

But it didn’t matter. Hayes and his soldiers overcame the mutineers again, and just as they took the rest of Cornelisz’s men hostage, the Sardem crested the horizon. Rescue had arrived.

The Aftermath of the Batavia

Pelsaert wasted no time in trying the mutineers.

As expected, Cornelisz and the worst of his men were executed by hanging, but not before having their hands chopped off. Two of the mutineers, Loos and a younger cabin boy were spared but abandoned on the Australian mainland.

What remained of Cornelisz’s crew were taken back to Batavia aboard the Sardem, where most of them were tortured or hanged. Surprisingly, Jacobsz survived the torture and was not executed due to lack of evidence and the fact that he had not taken part in the Beacon Island massacre.

The true hero of the situation, Hayes, was rewarded handsomely with a promotion and increased salary. With that final bit of justice, the tragedy of Batavia was ended, but the legend of what happened on those islands has never been forgotten.

References

“Wreck of the Batavia”

https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/wreck-of-the-batavia

“New horrors unravelled in the story of the Batavia shipwreck”