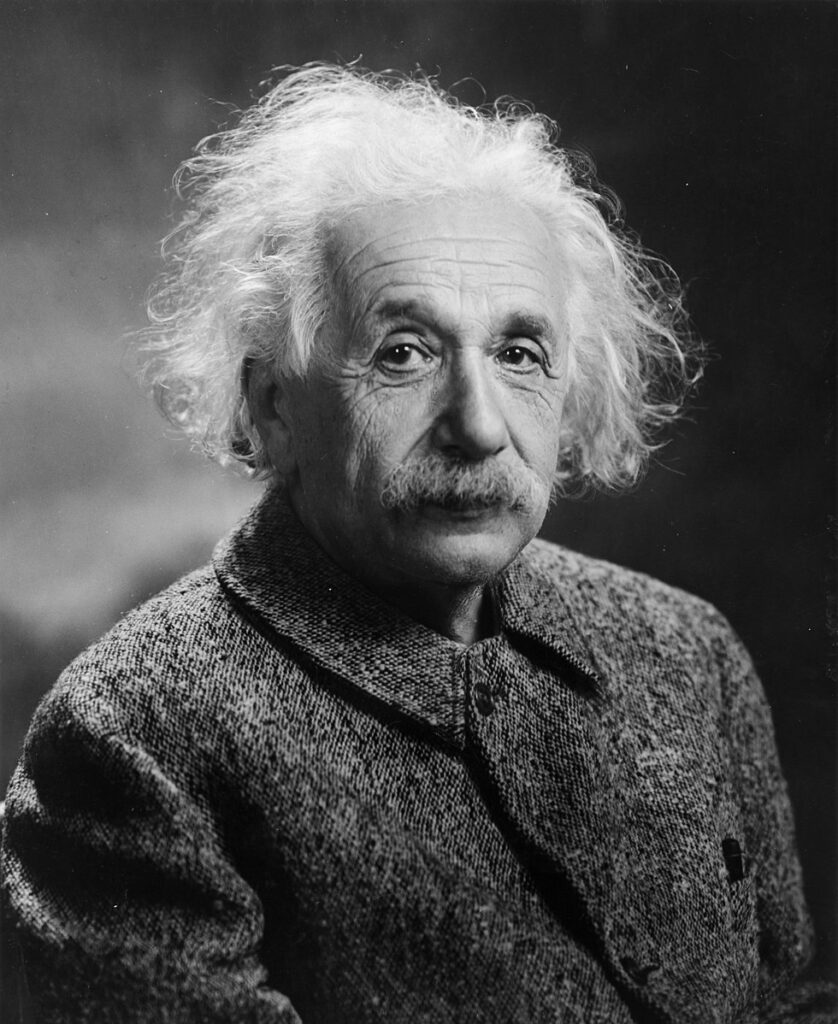

For over a century now, the name Albert Einstein has been synonymous with “genius.” The epitome of super-intelligence.

Every grade school student knows his name and millions of aspiring scientists study his theories hoping to discover a flicker of his brilliance in themselves.

Einstein is credited with presenting seven theories that literally changed our understanding of the universe. While few laymen can explain these theories in terms the average person can understand, most people do know that it was Einstein’s E=MC² formula that made the atomic bomb possible.

But what many do not know is that to his dying day, Einstein regretted making that discovery. He referred to it as the “One Great Mistake in My Life.”

Early Life

Albert Einstein was born on March 14, 1879, in Ulm, Kingdom of Württemberg (northern Germany), to Hermann and Pauline (née Koch) Einstein. While some biographies refer to Albert as the “middle” child, most accounts list only one sibling, a sister Maria, born on November 18, 1881.

Einstein’s mother, Pauline, is said to have been a domineering woman who instilled in her son the drive to succeed, but also an appreciation for the arts. She even encouraged him to play the violin.

Einstein’s father, Hermann, was an engineer and businessman. He is described as “otherworldly,” even “dreamy,” which likely inspired Einstein to always look beyond the obvious.

Einstein was described as a “self-sufficient and thoughtful” boy. He spent long hours building houses from playing cards and solving complex mathematical puzzles.

The young Einstein particularly enjoyed spending time with his uncle Jakob who was an engineer in business with his father. He sparked his interest in mathematics by lending him a book on algebra and sending him math puzzles to solve.

According to most biographers, Einstein first became interested in science at age five. It was when his father showed him a magnetic compass and he became fascinated by the way it continually points in the same direction no matter which way it is held.

This ignited not just a curiosity about “how” things work, but “why.”

Education

At age six, Einstein started attending the Petersschule on Blumenstrasse. This was a Catholic elementary school in Munich, Germany—which he immediately took a dislike to.

Having taken a particularly long time to solve basic mathematical problems, his teachers initially thought him “slow.” They did not realize that Einstein wasn’t trying to simply solve the problems, but trying to discover better ways of solving them.

This spawned a long-held misconception that Einstein couldn’t do simple arithmetic. In reality, he was a superior student who found the rote method of education boring.

In 1889, at age ten, Einstein was accepted into the Luitpold Gymnasium in Munich. This was a highly respected institution that emphasized Latin and Greek over mathematics and science.

Einstein was unhappy with the curriculum. Therefore he turned his attention to independent study.

In addition to his Uncle Jakob’s math puzzles, a friend of the Einstein family, a 21-year-old medical student named Max Talmud, lent him books on popular science and philosophy—which he eagerly devoured.

In 1894, Einstein’s father’s business, Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie, a factory that manufactured electrical dynamos (generators that produce [DC] direct-current) was on the verge of bankruptcy. This compelled Hermann to move his family to Italy in search of a new business venture.

Einstein remained in Munich to continue his studies. But by December of that year, he convinced the school administration to let him leave. He joined his family in Pavia.

A short time later, he wrote an essay that provided insight into the direction his mind was taking. It was called, “On the Investigation of the State of the Ether in a Magnetic Field.”

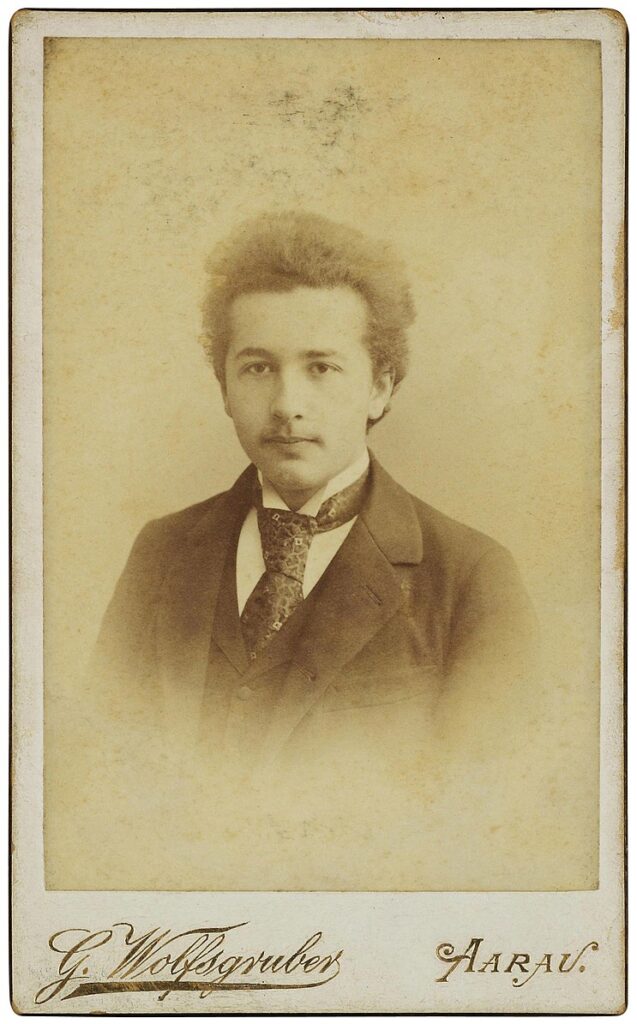

In the summer of 1895, at age 16, Einstein sat (but failed) the entrance exam into the Swiss Federal Polytechnic school in Zurich, Switzerland. Instead, he attended the Aargau Cantonal School in Aarau, Switzerland.

While lodging with the family of Professor Jost Winteler, Einstein began the first of many sexual relationships, with Winteler’s daughter, Marie. The following year he was accepted into the four-year mathematics and physics program at Swiss Federal Polytechnic.

At this same time, a bright and articulate graduate student named Mileva Marić (four years Einstein’s senior) was also enrolled there.

“Johnny and Dolly”

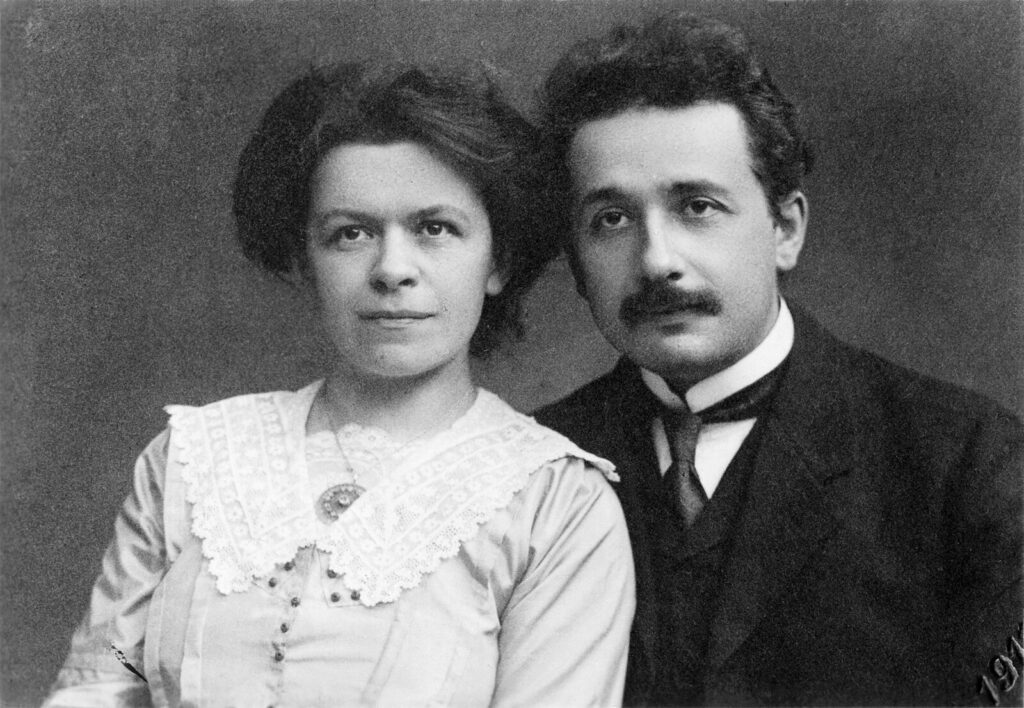

Instantly attracted, Einstein and Marić quickly became inseparable. They kept separate apartments for appearances, while pursuing an intense sexual relationship.

Calling themselves “Johnny and Dolly,” Einstein was so enamored with “Dolly” that he frequently wrote her love letters and poems. They included the passionate, “Who then Johnny boy, crazy with desire, while thinking of his Dolly, his pillow catches fire!”

But, neither the Einstein nor Marić family thought the relationship prudent, considering their ethnic differences. Einstein’s mother was horrified that her son would even consider marrying an “ethnically-inferior” Serbian woman, saying, “You are ruining your future and destroying your opportunities!”

In 1900, Einstein was awarded his teaching diploma. Marić, however, was denied, having failed the theory of mathematical functions portion of the exam.

Having previously renounced his German citizenship, that same year, Einstein became a Swiss citizen.

Marriage and the Pursuit of Greatness

In 1901, Marić announced that she was pregnant. Her pregnancy immediately put Einstein’s professional and social standing in jeopardy.

Having a child out of wedlock carried a severe social stigma. It could ruin any chances for the career he’d envisioned.

That same year, Einstein began his doctorate studies at the University of Zurich to meet the requirements for his Ph.D.

In early 1902, Marić gave birth to their illegitimate child. They had a daughter named Lieserl.

Biographers disagree as to the fate of the child. Some insist she was adopted, some that she died of scarlet fever at an early age.

In June of 1902, Einstein was appointed “Technical Expert, Third Class” at the Swiss Patents Office in Burn, Switzerland. Although he worked eight hours a day, six days a week, the schedule allowed him sufficient time to work on his scientific theories. And it gave him the financial security to support a family.

In January of 1903, the 24-year-old Albert Einstein married 28-year-old Mileva Marić. In May of 1904, the couple’s first son, Hans Albert Einstein was born.

Almost immediately, Einstein not only began ignoring his parental duties, he began distancing himself from his wife. In less than a year, their relationship was virtually non-existent. Preferring the solitude of his office, he sometimes didn’t come home for days.

E=MC²

After receiving his Ph.D. from the University of Zurich in 1905, Einstein produced four papers that would invariably change the course of known science.

They were:

- Special Theory of Relativity

- Establishment of the Mass-Energy Equivalence

- Theory of Brownian Motion, and the

- Foundation of the Proton Theory of Light.

These were produced at eight-week intervals. Fellow scholars could barely catch their breath following the first: the iconic, E=MC².

By 1908, Einstein was recognized as one of the world’s greatest scientists by the scientific community. The following year, he quit his position at the patent office to become a professor at the University of Zurich. Two years later, he became a professor at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic.

This would be followed by a professorial post at the University of Berlin, appointment as Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, and induction into the Prussian Academy of Sciences. At this time, Prussia comprised almost two-thirds of the total territory of the German Empire.

In 1912, Einstein began an affair with his cousin, Elsa Löwenthal. Three years his senior, Löwenthal was a wealthy divorcee with two daughters.

In a letter to her, Einstein wrote, “I would be so happy to walk just a few steps at your side without my wife, who is very jealous. I treat her as an employee whom I cannot sack.”

Soon after, Einstein gave Mileva a list of conditions she must meet to remain married: she was to speak to him only when he spoke first. When told to leave his study (where he indulged in his sexual trysts), she was to do so without hesitation. He made it clear that he would not compromise.

In 1914, Einstein accepted a professorship at the University of Berlin. His wife and children initially followed but then returned to Switzerland after just three months.

A World at War

When WW I broke out in July of 1914, Einstein made his pacifist beliefs known. He withdrew to his work. Now nearly 10 years since his groundbreaking theories were published, they remained unproven.

His personal life was now a series of sexual encounters. His professional life was stagnant. He grew depressed that he hadn’t achieved the renown he’d expected by this time in his life.

Moreover, Einstein found the “war fever” his colleagues were caught up in disgusting. He encouraged his influential associates to stop the war.

In reaction to a manifesto published by his fellow scientists in support of Germany’s hostility, Einstein initiated a petition seeking peace. However, he only received three signatures.

Growing hopeless, he reached a point of physical and mental exhaustion.

In 1916, Einstein collapsed; left alone but for his cousin Elsa Löwenthal. Content to put her life on hold to nurse him back to health, the bond between them intensified. Einstein planned to sever ties with Mileva and their children, and make Elsa a permanent part of his life.

Divorce, Marriage, Vindication, Celebrity

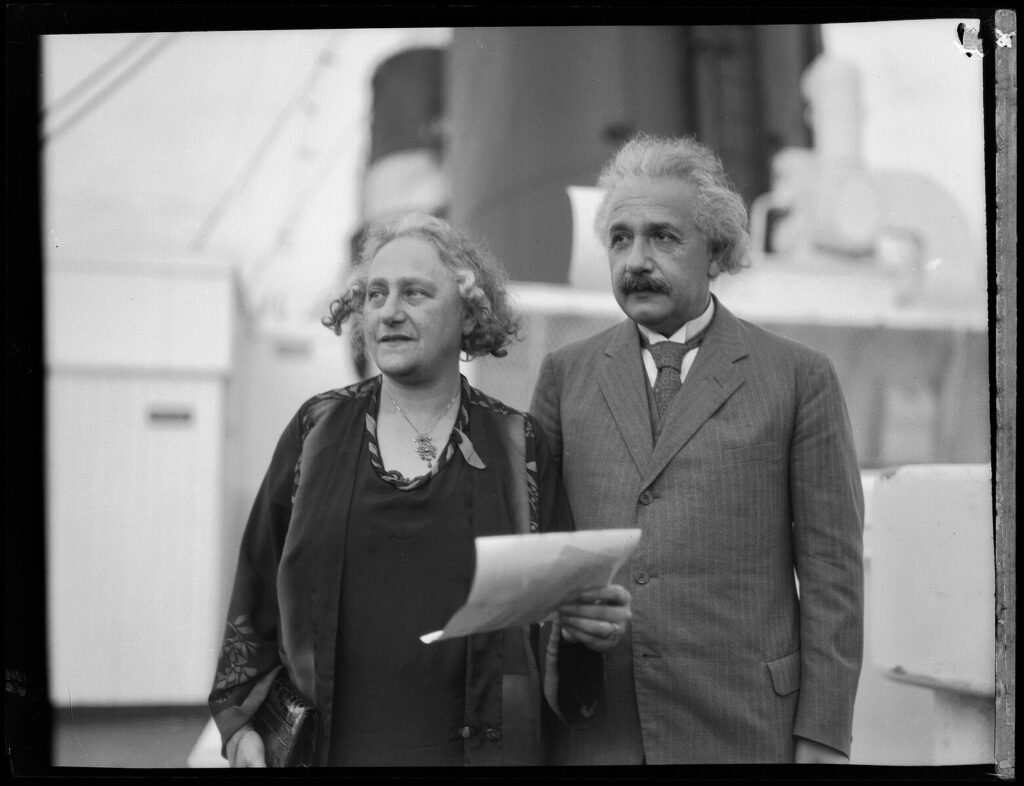

On June 12, 1918, Einstein and Mileva divorced. One year later, Einstein married his cousin Elsa Löwentha.

Unlike his first wife, Elsa was willing to put her personal needs second to those of Einstein and his work. She was happy preparing dinner parties for his friends. She disappeared into the background when necessary. She ignored Einstein’s many sexual dalliances.

In 1919, Einstein’s Theory of Relativity was proven correct—and by a relatively rare natural occurrence: a solar eclipse. Now at age 40, Einstein was an instant celebrity.

He was the scientific community’s first “superstar.” Overnight, he became one of the most recognized individuals on the planet.

In April of 1921, the Einsteins embarked on a tour of America, visiting New York City. They were welcomed as veritable royalty. Everywhere they went, crowds gathered.

While Elsa thoroughly enjoyed the attention, Albert found the adulation perverse. The Press camped outside his door waiting for a glimpse or a quick photo; a clever quip or quote for the next edition.

The following year, the Einsteins began a six-month speaking tour of Asia. They visited Singapore, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Japan. They met the Emperor and Empress at the Imperial Japanese Palace.

On his return trip, Einstein made what would be his only visit to Palestine. In his travel diary Einstein wrote, “Dull-minded tribal companions are praying, faces turned to the wall, rocking their bodies forward and back. A pitiful sight of men with a past but without a future.”

In November of 1922, Einstein won the 1921 Nobel Prize for Physics; but not for his work on relativity and gravitation as expected.

The Coming of a Second World War

For the next ten years, Einstein spent much of his time traveling, lecturing on his newest discoveries to throngs of devoted fans (and women wanting to share his bed). He became one of the most popular speakers of the era.

In Germany, however, a much different backstory was unfolding. There, he was not a genius who could benefit the world, but a Jew who sought to undermine the German cause.

By 1932, Hitler was quickly becoming Germany’s supreme dictator—which meant no Jew was safe. Particularly not one who’d sought to undermine Germany’s efforts to take a major step forward on the world stage.

Referred to by his countrymen as “Einstein the Jew,” the Nazi Party depicted him as a traitor to both his people and the German Empire. They ultimately placed a bounty on his head.

With Europe becoming an increasingly dangerous place for him and his family, in December of 1932, the Einsteins (including Elsa’s two daughters) escaped to America.

Man Without a Country

By February of 1933, the Einsteins had established themselves in America. Albert immediately plunged himself back into his work at his new residence in Pasadena, California.

Suddenly, the scientific leaps he’d made decades before were receiving a great deal of attention. But, not for the advancement of humanity they offered—only for their potential destructiveness.

In 1935, at the age of 56, Einstein accepted a position at Princeton University (Princeton, New Jersey) at the Institute for Advanced Studies. He turned his attention to his “Unified Field” theory.

This theory was an attempt to explain all the forces of nature in one equation. He pursued what he thought of as “absolute objective truth,” truth that can only be achieved through mathematics.

In the fall of 1935, Elsa fell seriously ill. Uncharacteristically, Einstein set his personal affairs aside and tended to her needs. On December 20, 1936, at the age of 60, Elsa died, after almost 17 years of marriage.

“The Bomb”

Returning to his work immediately after Elsa’s death, Einstein prepared to delve full-bore into a number of new theories he’d been envisioning. That work, however, was soon interrupted.

A group of immigrant scientists approached him with news that the German military was developing a devastating new weapon.

Einstein suddenly realized that if his theory led to technology allowing the Nazis to create an atomic bomb, world annihilation was almost certain. Though he knew theoretically that his theory could be applied to building a weapon, only now did he consider that a world power would actually consider doing that.

Europe was on the verge of a second world war and Hitler was in ultimate power. Einstein reasoned that if the Germans built an atomic bomb before the Americans, Hitler would be in a position to give the US the ultimatum of accepting his rule–or be wiped out of existence.

He had no choice but to reevaluate his lifelong position on pacifism. On August 2, 1939, Einstein co-signed a letter to US President Theodore Roosevelt.

He alerted him that it “may become possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium-like elements would be generated [that] would also lead to the construction of . . . extremely powerful bombs of a new type.”

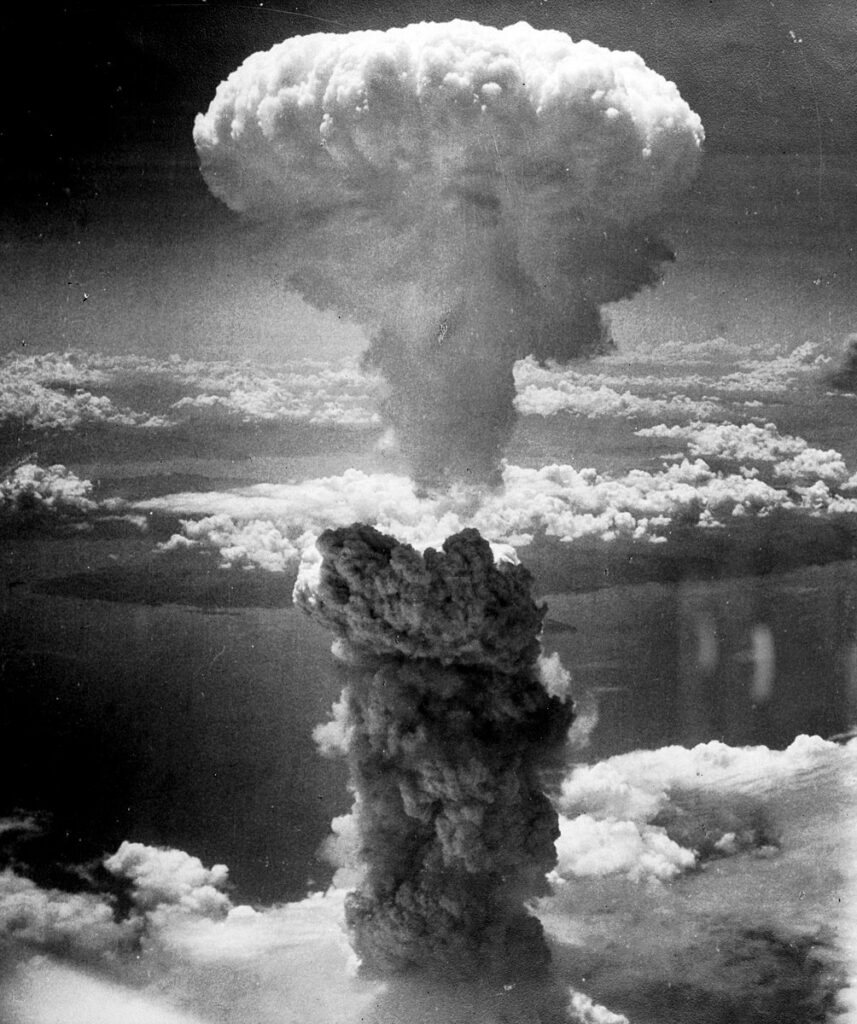

This letter set into motion the Manhattan Project. This was a research and development program instituted by the US, UK, and Canada to produce the first atomic weapon.

The following year, Einstein was granted American citizenship.

In August of 1945, the US dropped two bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It obliterated more than 200,000 people.

On July 1, 1946, Time magazine put Einstein’s likeness on its cover, with a mushroom cloud erupting from behind him with E=MC² emblazoned on it.

Einstein, the Subversive

Horrified by the destruction his scientific theory had enabled, Einstein used his celebrity to campaign against the future use of weapons of mass destruction.

His outspoken views, however, ultimately brought him powerful enemies. These included FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, Senator Joseph McCarthy, and several members of the US State Department.

In 1947, Newsweek ran a cover with Einstein’s likeness under the condemning headline, “The Man Who Started it All.”

When interviewed, Einstein is quoted as saying, “I could burn my fingers that I wrote that letter to President Roosevelt. Had I known the Germans would not succeed in producing an atomic bomb, I never would have lifted a finger.”

(Ironically, Einstein was never invited to work on the Manhattan Project and was, in fact, intentionally left out of the “loop” so that he’d have no say-so as to its use.)

The Death of Genius

By 1948, Einstein’s overall health was failing. Plagued by chronic stomach pain and anemia, doctors discovered an aneurysm in his abdominal aorta.

Although surgery was an option, Einstein chose instead to take an extended vacation in Sarasota, Florida. By his reasoning, he’d lived long enough and had given the world all that he could.

On April 11, 1955, Einstein signed what would become known as the “Einstein-Russell Manifesto.” It was a petition urging the abolition of not just weapons of mass destruction, but war itself.

It advocated giving power over nuclear weapons to the United Nations in an effort to work towards peace rather than war.

In mid-April of that year, Albert Einstein collapsed. The aneurysm burst. On April 18, 1955, he died at Princeton Hospital at the age of 76.

To his dying day, Einstein agonized over the theory he’d hoped would change the world for the better—but instead threatened its very existence.

References

interestingengineering.com., “7 of Albert Einstein’s Theories that Changed the World,” Albert Einstein Inventions: Albert Einstein Theories that Changed the World (interestingengineering.com)

sparknotes.com., “Albert Einstein,” https://www.sparknotes.com/biography/einstein/section1/

albert-einstein.org., “The Albert Einstein Archives,” http://www.albert-einstein.org/

britannica.com., “Albert Einstein,” https://www.britannica.com/biography/Albert-Einstein

historynet.com., “EINSTEIN HELPED INVENT THE A-BOMB, BUT HE WATCHED ITS DEPLOYMENT IN HORROR,” https://www.historynet.com/einstein-and-the-bomb/

discovermagazine.com., “Chain Reaction: From Einstein to the Atomic Bomb,” https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/chain-reaction-from-einstein-to-the-atomic-bomb

royalsocietypublishing.org., “Albert Einstein, 1879-1955,” https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsbm.1955.0005