What we know (or think we know) about history is only a minute sliver of what humans have accomplished and experienced over the millennia. Each year, the tireless work of archeologists adds a few more pieces to the puzzle and increases our understanding of human history.

Here are some of the most important archaeological discoveries of 2023, beginning with a ground-shaking discovery about hominid civilizations and taking us all the way up to a WWII maritime tragedy.

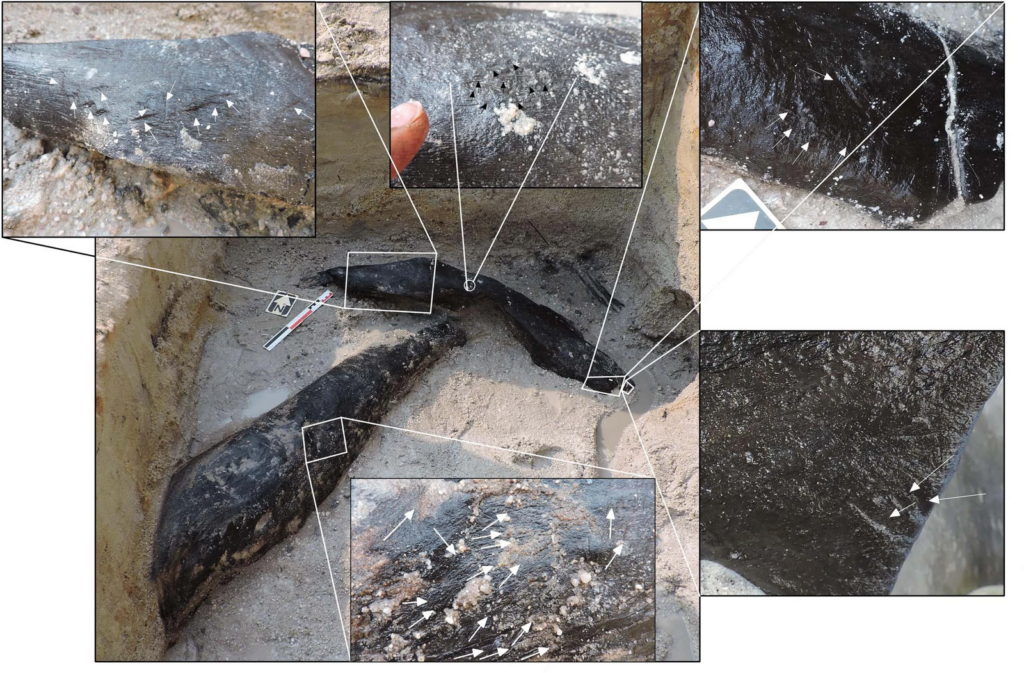

1. The World’s Oldest Wooden Structure

First excavated in 2019, the Kalambo structure in Zambia was determined in 2023 to be at least 476,000 years old. The structure, according to one of the archeologists tasked with studying it, “involves the intentional shaping of two trees to create a framework of two interlocking supports.”

The age of the structure was determined through a new technique called luminescence dating. This measures how much time has passed since certain minerals were last exposed to sunlight.

This structure predates Homo sapiens. This revolutionizes our understanding of what our early hominid ancestors were capable of.

Hundreds of thousands of years ago, hominins notched logs with tools (most likely a stone adze) to secure them together and create a platform. Another log showing similar preparation has also been found nearby.

It also suggests that they stayed in one place for long periods of time, challenging the popular notion that these early hominins were nomadic hunter-gatherers.

Wooden tools have also been found in the area, but they were created much later. Archeologists believe that wooden tools were extremely common during the Stone Age – probably even more common than stone tools. But wood is so rarely preserved for such immense lengths of time that few examples have been found.

No hominin remains have been found at the site. Therefore, we can’t be sure which species of archaic humans created this ancient wooden structure.

The most likely candidate is Homo heidelbergensis, often thought to be the last common ancestor of humans and Neanderthals. Their size, including their brain size, was comparable to modern humans.

2. The 54,000-year-old Arrowheads

Archeologists excavating a cave in France discovered the earliest evidence of bow-and-arrow technology ever found outside of the continent of Africa (where humans were using this technology 64,000 years ago).

In this cave inhabited by early modern humans over 54,000 years ago, archeologists found over 300 arrowheads. They were attached to shafts of wood with glue made from ocher, tree sap, and beeswax.

The humans who created these arrowheads may have been the first Homo sapiens to arrive in the region, long after the Neanderthals. These projectile weapons may have given our human ancestors the edge over their Neanderthal cousins, who only used spears.

Both groups coinhabited the region for another 14,000 years and occasionally interbred.

3. The Oldest Writing Ever Discovered

In addition to the famous cave paintings and carvings of human and animal figures, hundreds of caves throughout Spain and France are also marked with non-figurative symbols dating back over forty thousand years.

While archeologists have known about these signs and symbols for well over one hundred years, it wasn’t until 2023 that they began to piece together the meaning of this proto-writing.

Using a database that documents these ancient symbols, archeologists have been able to guess at the meanings of some of the most commonly used shapes. If they were truly used to record information and communicate meaning, these symbols are the earliest example of writing ever found.

One of the most frequently occurring signs is shaped like a Y. Context clues suggest that this symbol meant ‘to give birth’.

It was surrounded by other symbols that indicated the time of year. It was a sort of calendar that marked the season for various animals that these Neolithic peoples depended upon for their survival.

Archeologists compared symbols of lines, dots, and Y’s that accompanied depictions of animals to the mating and birthing seasons of each one. They were able to show that these neolithic peoples were using this proto-writing to record the birthing seasons for various mammals, fish, and birds.

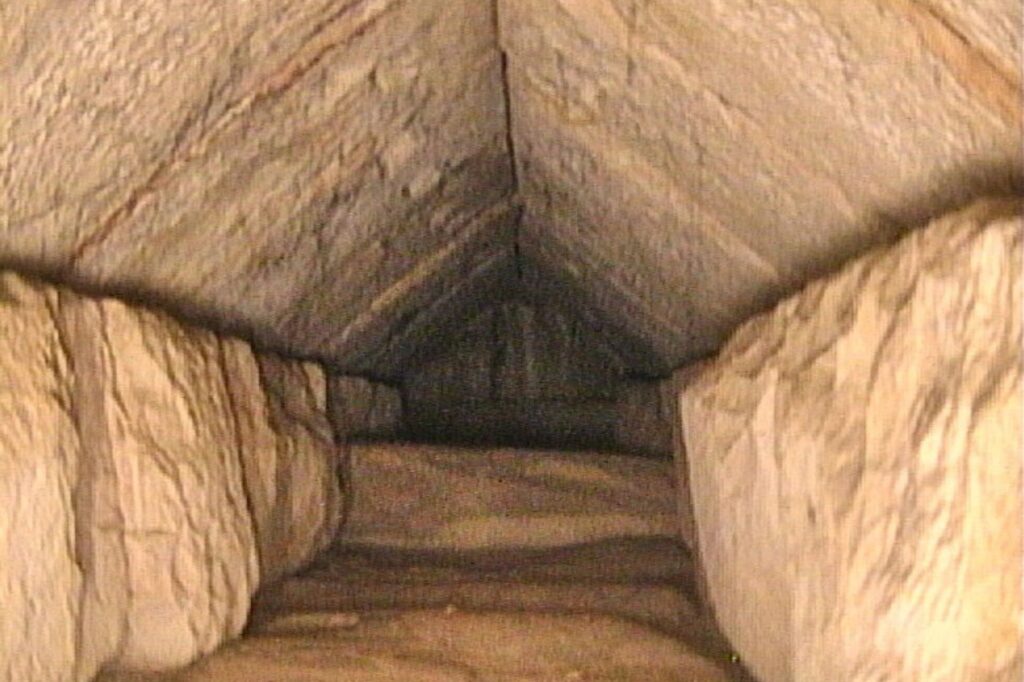

4. A Hidden Chamber in the Great Pyramid of Giza

The Pyramid of Khufu – better known as the Great Pyramid of Giza – is over 4,500 years old. It is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World to still exist. Modern archeologists have yet to uncover all of its secrets.

A system of technologies called ScanPyramids uses infrared thermography, ultrasound, cosmic-ray radiography, and 3D simulations to gather information about ancient structures. This program has been in place since 2015, and just this past year, researchers used it to discover a sealed corridor above the main entrance to the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Following this discovery, researchers fed a tiny camera between cracks in the stones to capture images of the passageway, which is approximately thirty feet long and nearly seven feet wide.

Experts have yet to reach a consensus on the purpose of the corridor.

The head of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, Mostafa Waziri, suggested that it may exist to redistribute weight above the main entrance and maintain the structural integrity of the pyramid. Other scholars are hopeful that it might lead to other hidden chambers.

As the ScanPyramids project continues, we may learn that these massive edifices are less solid than originally believed. Many of these hidden chambers may have simply served to decrease the amount of stone needed for these truly gargantuan construction projects.

5. The 4,500-year-old Palace

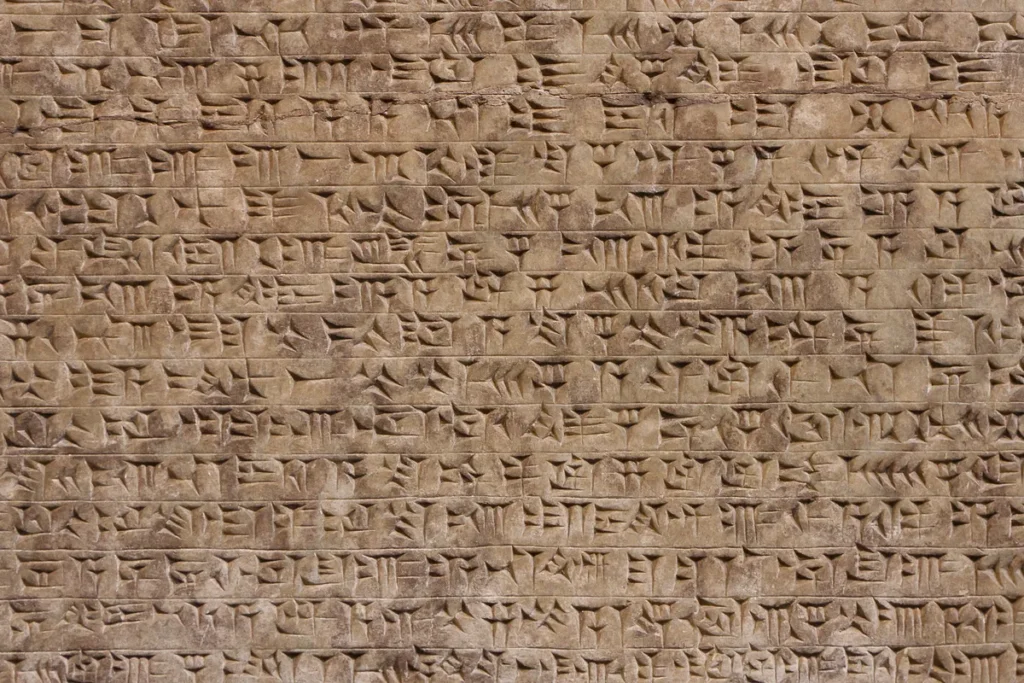

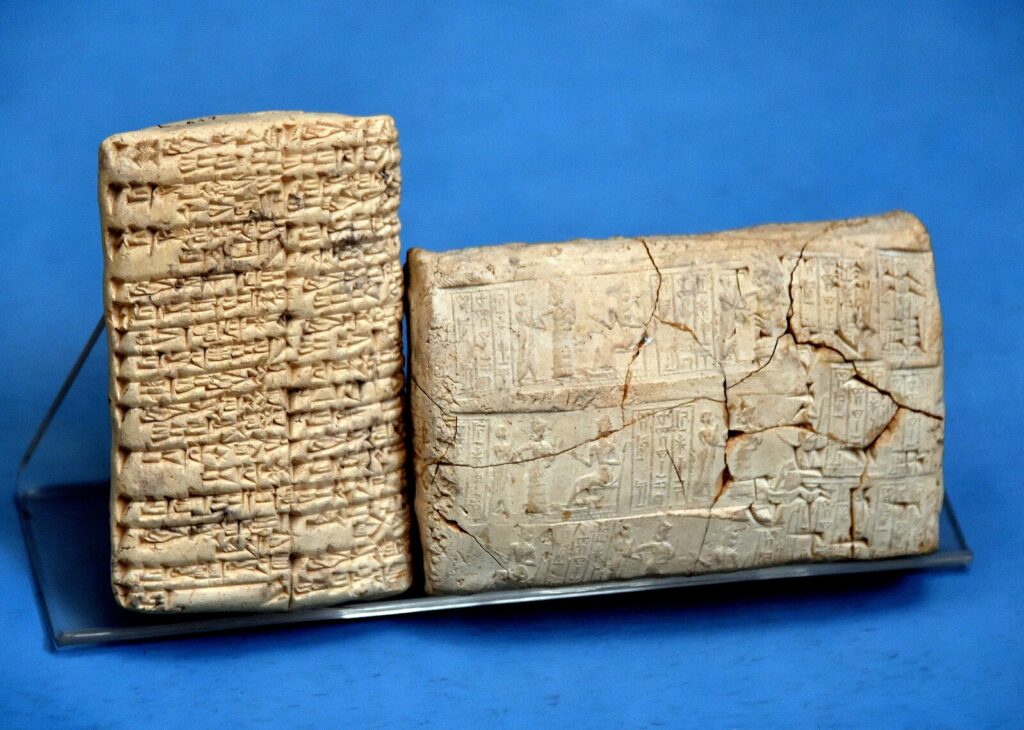

Another major discovery of 2023 is a palace in Iraq that is just as old as the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The Lord Palace of the Kings was built in the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu in modern-day Iraq. The ancient Sumerians built the earliest cities ever discovered, invented writing, and created the first documented codes of law. Girsu was one of about a dozen city-states.

The discovery also included an ancient temple dedicated to Ninĝirsu, an ancient Sumerian god of healing and agriculture. Eninnu, the White Thunderbird temple, was one of the most important temples in all of Mesopotamia.

The palace was constructed of mud bricks in the midst of a city that included an advanced canal system spanned by bridges.

More than two hundred cuneiform tablets have been discovered there. These ancient administrative records provide insight into the inner workings of this ancient city.

Hartwig Fischer, the director of the British Museum, called the Lord Palace of the Kings “one of the most fascinating sites I’ve ever visited”.

6. Lijiaya Culture Artifacts

Archeologists discovered a number of tombs belonging to high-status members of the Lijiaya culture in Qingjian, northern Shaanxi, China. The team at the Zhaigou archaeological site has also unearthed rammed earth buildings, cemeteries, and hundreds of artifacts.

The nine high-status tombs found at this site “are the largest and most numerous high-status tombs discovered in northern Shaanxi so far,” said Sun Zhanwei of the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology.

Burial offerings found at the site include axes and arrowheads made from copper, seashells, jade artifacts, a swallow-shaped belt buckle made from copper and inlaid with turquoise, a turquoise-inlaid bone casket, gold earrings, and a complete set of bronze chariots and horses.

Researchers say that these findings have increased their understanding of how this area fit into the Shang Dynasty and how the core area of this culture interacted with its northern territories.

7. Bronze Age Hallucinogens

Menorca, an island in present-day Spain, was first settled during the early Bronze Age. Starting around 1450 BC, locals interned their dead in natural caves closed off with walls constructed of large, closely fitting stones.

Archeologists recovered a hair sample from one of these tombs. They performed a chemical analysis using Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry that detected traces of alkaloids ephedrine, scopolamine, and atropine.

These were present in levels high enough to support the use of local plants for psychedelic purposes, most likely in shamanic ceremonies.

8. The First Human Representations of an Ancient People

In April 2023, archaeologists excavating in the south of Spain at a site called Casas del Turuñuelo uncovered the earliest human representations of the ancient Tartessos people. The stone busts were created around 500 BC.

The Tartessians were skilled metalworkers who created ornate jugs, incense burners, belt buckles, and more. This Bronze Age civilization spoke a Celtic language called Tartessian and used a writing system called Southwestern script.

Other Tartessian statues have been found, such as a winged cat currently located at the Getty Museum. But this recent discovery is the first example of human representations among the Taressians.

These life-sized human heads are intricately carved: they have textured hair, pointed noses, smiling mouths, and huge earrings. Archeologists believe that they represent Tartessian goddesses.

Other fragments were also found, including a piece of a statue depicting a Tartessian warrior wearing a helmet. These stone artifacts were found among great piles of animal bones, suggesting an important sacrificial ceremony.

9. Hundreds of Roman Forts

Also in 2023, a research project mapped and described 396 previously unidentified forts or fort-like archaeological sites throughout the desert margins of eastern Syria and north-western Iraq using satellite imagery.

This discovery builds upon findings from nearly a hundred years prior. Jesuit French priest Father Antoine Poidebard executed the novel idea of aerial archaeological surveys. He flew over Syria, Iraq, and Jordan in a small plane and took hundreds of pictures of ancient forts.

Poidebard’s aerial photographs from 1934 inspired this recent study. It used declassified, Cold War-era CORONA and HEXAGON satellite imagery to locate rectangular shapes indicative of ancient forts.

The majority of these forts were constructed and used between the second and sixth centuries AD. Rather than existing to defend the Roman frontier, as originally thought, scholars now believe that these hundreds of forts existed to support interregional trade.

Their presence enabled safe passage, provided food and water to people and their animals, and gave them a safe place to sleep. They probably also guarded strategic oases and provided sedentary populations with protection against raids by nomadic groups.

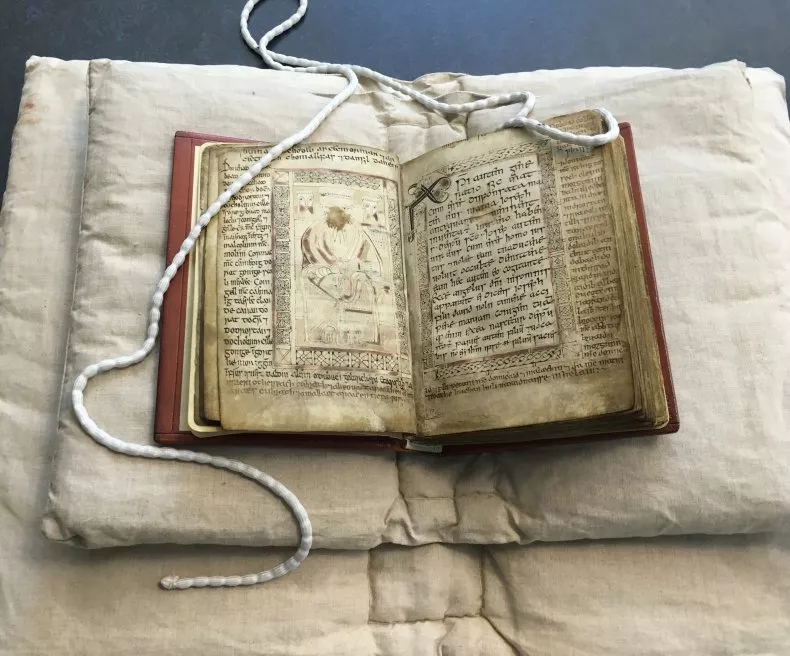

10. A Long-lost Scottish Monastery

A team of archaeologists discovered the location of the long-lost Monastery of Deer in Northeast Scotland. This is the place where the earliest written Scots Gaelic was produced in the late 11th and early 12th century.

The earliest surviving Scottish Gaelic writing is found in the Book of Deer, a pocket gospel book written on vellum in brown ink. It’s a linguistic hodgepodge, with portions of the gospels written in Latin and a colophon at the end in Old Irish.

The Scottish Gaelic texts are written in the blank spaces surrounding the rest. These marginalia, written by as many as five different people, include an account of the founding of the monastery at Deer and records of land grants to the monastery.

The monastery was discovered just eighty meters away from the ruins of Deer Abbey, which was founded in 1219. Carbon dating matches the age of the building to the time period in which the addendums were written.

The team also recovered remnants of daily life indicative of a monastery, including boards for a popular game called hnefatafl. Also known as Vikings Chess, the game originated with Nordic peoples and became popular throughout northern Europe.

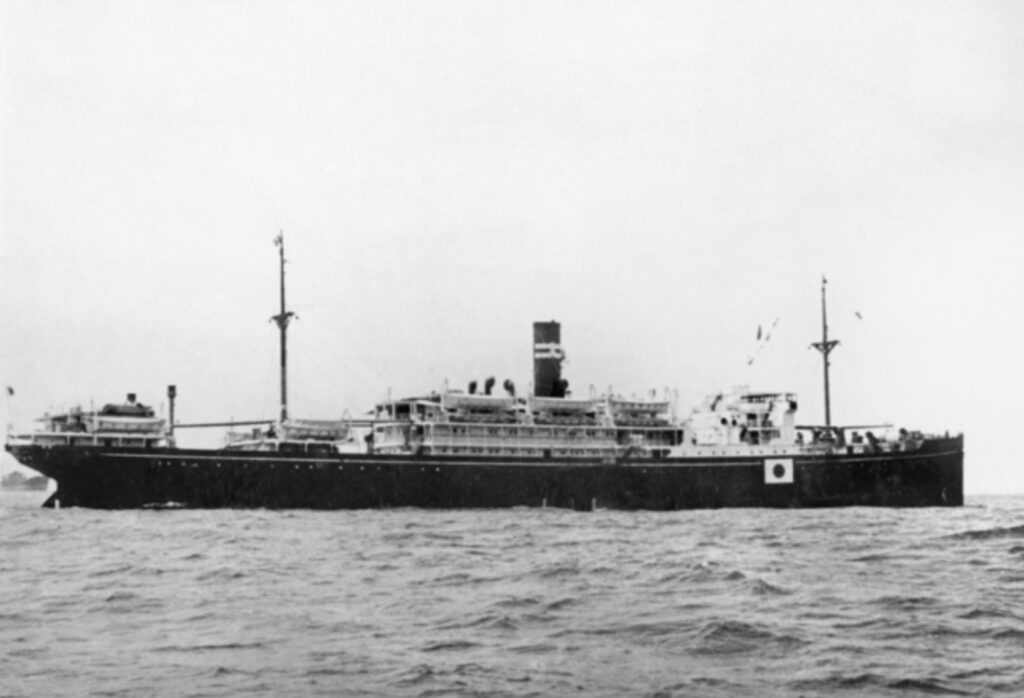

A Maritime Tragedy

The SS Montevideo Maru was recovered in 2023, 81 years after it sank.

The Japanese transport ship was carrying more than one thousand prisoners, most of them Australian, when it was torpedoed by an American submarine. Most of the families who lost men aboard the Maru weren’t notified for years.

Lost for decades, the ship was finally found by a team of deep-sea survey specialists. It rests under 4000 feet of water, even deeper than the Titanic. The wreck will be studied further, but the victims’ remains will not be disturbed.

“We should refer to it as not a wreck but a tomb,” said submarine specialist Captain Roger Turner, whose years of research made this discovery possible. “It’s where more than 1,100 souls now lie at peace.”