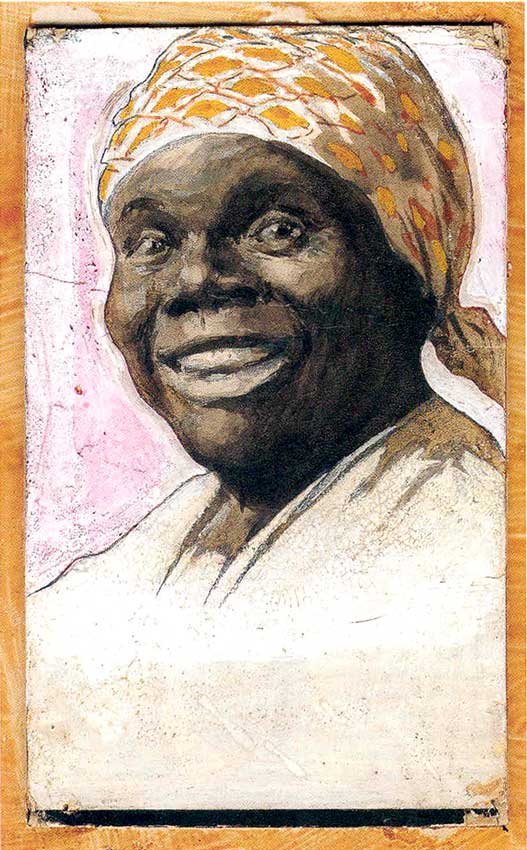

At the age of 59, Nancy Hayes-Green made her debut as “Aunt Jemima” at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago, Illinois. She became the first Black corporate model in American history hired to promote a nationally distributed product.

In character, “Aunt Jemima” stood beside what was touted as the “world’s largest flour barrel” (24 feet tall), where she operated a pancake-cooking display, sang Civil War era songs, and romanticized about the Old South. She claimed, for the good of the product, that life in those times was happy for both Blacks and Whites.

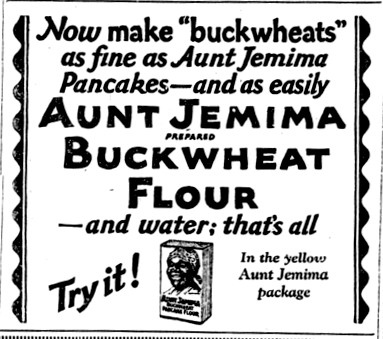

The product she endorsed was a self-rising “ready-mix” pancake flour developed by the Pearl Milling Company in 1889. It was the first of its kind, so there was no fear from competitors.

The question was, would traditional homes across the South choose a “ready-made” flour mix over “made-from-scratch?”

Pearl Milling owners, Chris Rutt and G. Underwood, thought consumers might choose their new product if endorsed by a jovial-looking, rotund Black woman fitting the “mammy” archetype common to Vaudeville House skits. And judging by the reaction “Aunt Jemima” received at the Expo, they were correct.

Soon, Pearl Milling added maple syrup and other breakfast food products to their line-up—all with “Aunt Jemima” on the label. “Aunt Jemima” became one of the most recognized faces in America.

“Aunt Jemima” changed little over the years. She slimmed down in 1968, and in 1989 lost her trade-mark head-covering and her plain white collar was replaced with lace. But she remained a familiar face on breakfast tables in millions of homes around the world.

Until 2020, that is.

In June of that year, new owners PepsiCo (parent company of Quaker Oats, new owner of the Aunt Jemima franchise), announced that the Aunt Jemima brand would be discontinued, “to make progress toward racial equality.”

In June of 2021, amid heightened racial unrest in the US, Aunt Jemima was re-branded as the Pearl Milling Company. And while the “Aunt Jemima” name remains in use (for now), the familiar, round Black face has disappeared.

The brand’s tagline now reads, “Same great taste as Aunt Jemima.” Many are not happy that such a drastic measure has been taken.

Early Years

Nancy Hayes (Green) was born a slave in the “Antebellum” South (1812-1861) on March 4, 1834, on a farm on Somerset Creek. This was six miles outside Mount Sterling, in Montgomery County, Kentucky.

Her relationship with the man named George Green is unclear as there were no birth certificates nor marriage licenses issued for enslaved people. Green is known to have raised tobacco, hay, cattle, and hogs; and fathered several children with Hayes-Green.

According to oral history, Hayes-Green was at various times a servant, nanny, wet nurse, housekeeper, and cook for slave owners Charles Morehead and Amanda Walker.

Hayes-Green also served as domestic to the Walker family’s next generation (presumably as nanny and cook). Walker’s two sons later became well-known Chicago Circuit Judges, Charles M. Walker Jr., and Dr. Samuel J. Walker.

By the end of the American Civil War (1865), Hayes-Green had lost her husband and children (most likely to disease). For the next five years, she lived in a simple wood-frame shack (still standing as of 2014) behind the Walker grand home on Main Street, in Covington, Kentucky.

In the early 1870s, Hayes-Green (who now went simply by Nancy Green), accompanied the Walkers to Chicago. This was sometime before the birth of Samuel Walker’s youngest child in 1872.

The Walker family settled in an upper-class residential district near Ashland Avenue and Washington Boulevard. The area was called the “Kentucky Colony,” named for a community of displaced Kentuckians.

The R.T. Davis Milling Company

The R. T. Davis Milling Company owners Chris Rutt and G. Underwood were looking for a “mammy” archetype to promote their product. They wanted the image of a traditional Black servant in a White Household.

It was Judge Walker who suggested Green try out for the part; portraying the fictional “Aunt Jemima.” Rutt came up with the marketing idea after seeing a poster for a minstrel show appearing at a Vaudeville house in St. Joseph, Missouri.

After appearing at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, Green is said to have been offered a lifetime contract to portray “Aunt Jemima” and promote the pancake mix. It has also been suggested that the lifetime contract never existed and was created years later to add to the “Aunt Jemima” legend.

The Expo marked the beginning of a major promotional push by the company. This included hundreds of personal appearances and Aunt Jemima merchandising.

Green appeared at fairs, festivals, food shows, flea markets, and local grocery store openings—always as “Aunt Jemima.” She became a celebrity almost over night. Her arrival was announced on large billboards featuring the catchphrase, “I’s in town, honey.”

Look-A-Likes and Deception

In 1899, Green was asked to travel to Europe to appear as “Aunt Jemima” at the 1900 Paris Exhibition. Too fearful to cross the Atlantic Ocean, she was promptly replaced by a 60-year-old Black woman named Agnes Moodey, the first of many look-a-likes.

Moodey appeared at countless venues throughout France. Her appearance fooled thousands of unsuspecting “Aunt Jemima” fans.

Hiring Moodey marked the beginning of years of deception. This was based on the R.T. Davis Milling Company’s belief that the public couldn’t distinguish one rotund, middle-aged Black woman from another.

Meanwhile, the original “Aunt Jemima,” Nancy Green, was busy making appearances across the US as usual. All the while, (according to the US census) she was continuing to work at her domestic duties.

In 1909, the R. T. Davis Milling Company took the deception one step further. They produced a print ad for “Aunt Jemima’s Pancake Flour” depicting what was obviously a very different woman from Nancy Green.

In actuality, she was an identified actor hired just for the part. In that Davis Milling considered the image a caricature (an artist’s rendering) rather than the portrait of the actual spokeswoman, Green was neither consulted nor compensated.

Logos and Trademarks

In 1915, the Aunt Jemima brand became the basis for a trademark ruling that set a new precedent in the US.

Before this time, American trademark law protected against infringement by other sellers attempting to market the same product. However, under the “Aunt Jemima Doctrine,” the Davis Milling Company was also protected against infringement by an “unrelated seller of a different but related product”–in this case, pancake syrup.

Due to this ruling, Aunt Jemima became one of the longest, continually-running logos and trademarks in the history of American marketing.

This landmark ruling provided unprecedented protection to the R.T. Davis Milling Company regarding any subsequent products that carry the Aunt Jemima name and/or likeness.

However, it in no way protected Nancy Green (or any other Black woman hired to portray “Aunt Jemima”). It also did not provide compensation to their heirs for continued use of their likeness.

This is because Green (and all the others) were paid to personify a fictional character; not be the literal “face” of the products. As such, many people were unaware of Nancy Green’s role in creating the “Aunt Jemima” character.

In her later years, Nancy Green lived in relative anonymity with her nieces and nephews in Chicago’s Fuller Park and Grand Boulevard neighborhoods. However, she was tragically struck and killed in a freak auto accident (in which a driver jumped the curb) on August 30, 1923, at the age of 89.

Quaker Oats

In 1926, the Quaker Oats Company purchased the Aunt Jemima brand. This effectively severed any previous obligations made to models or spokespersons.

Just prior to taking over the million-dollar company, Quaker contacted Lillian Richard. Lillian was a cook from Hawkins, Texas.

They invited her to portray the “Aunt Jemima” character. They wanted her to demonstrate pancakes and other products at various venues in nearby, Paris, Texas.

Richard’s “career” officially lasted 23 years. Then, in 1935, representatives of the Quaker Oats Company discovered South Carolina native Anna Short Harrington.

She was cooking pancakes at the New York State Fair, outside Syracuse. They approached her to model for a print ad in the monthly magazine, Woman’s Home Companion.

This led to additional appearances as “Aunt Jemima.” This included appearing at the Post-Standard Home Show in 1954, an annual four-day exposition where new innovations for the home were on display.

Finding Harrington’s South Carolinian accent charming, organizers encouraged her to repeat the catchphrase, “Let ol’ Auntie sing in yo’ kitchen.”

Anna Short Harrington died of natural causes in 1955, at the age of 58. Lilian Richard suffered a stroke in 1947 and died in 1956 at the age of 65.

Although Harrington fared somewhat better financially due to her association with larger venues, Richard made far less as “Aunt Jemima.” But both did considerably better, financially, than Nancy Green.

Rebranding and Trademark Violation

On June 27, 2020, Quaker Oats announced that the Aunt Jemima brand would be discontinued. They replaced it with a new name and image “to make progress toward racial equality.”

Within days, a number of other products now under the PepsiCo (Quaker) umbrella (including Uncle Ben’s rice, Mrs. Butterworth’s pancake syrup, and the “Rastus” Black chef logo used by Cream of Wheat) also discarded their decade’s-old product icons.

Amid a hailstorm of protests, descendants of “Aunt Jemima” models Lillian Richard and Anna Short Harrington vocally objected to the change. They attempted to stop it.

Vera Harris, a family historian for the Richard family, went on record as saying, “I wish we would take a breath and not just get rid of everything. Because good or bad, it is our history.”

Similarly, Harrington’s great-grandson, Larnell Evans, said, “This is an injustice for me and my family. This is part of my history.” (Evans had previously filed and lost a lawsuit against PepsiCo/Quaker Oats claiming he and his family are owed millions in compensation.)

Ongoing Legalities

On February 9, 2021, PepsiCo (who now owns Quaker Oats) announced that the replacement brand name for Aunt Jemima (and related products) would be Pearl Milling Company.

PepsiCo purchased that name for that specific purpose on February 1, 2021. The re-branded products appeared on shelves that June, one year after the company announced they would drop Aunt Jemima branding.

PepsiCo intended to reference the Aunt Jemima logo on the packaging for a six-month period after the re-brand. This was so consumers unaware of the sociopolitical drama being played out wouldn’t assume the product line hadn’t been completely discontinued.

PepsiCo, however, was subsequently informed that even after that adjustment period, it wouldn’t be legal to permanently abandon the Aunt Jemima brand due to trademark law. If it did, a third party could obtain and use the brand.

Social Media

In 2021, Aunt Jemima/Pearl Milling Company unveiled the newly designed pancake mix and syrup packaging on the Aunt Jemima website. It featured a rendering of a mill with a water wheel on a red, white, and yellow color scheme.

Both products included labeling announcing, “New Name Same Great Taste Aunt Jemima.”

In addition to the re-branding, the newly (re)established Pearl Milling Company stated that it was making a $1 million commitment to “empower and uplift Black girls and women.” This money is in addition to a $400 million, five-year investment to “support Black business and communities” and to increase Black representation at PepsiCo.

And while many say PepsiCo’s decision to phase out the “Aunt Jemima” logo is a good start at achieving equality for Blacks in America. Others say it’s not nearly enough, while others fear having their history erased from the past by a thoughtless and reckless decision.

Consensus

As most socially-conscious Americans are aware, the decision to phase out the stereotypical image of a slave-era Black woman from pancake boxes and syrup bottles didn’t come about as a marketing strategy.

It came about amid worldwide outrage sparked by the murder of George Floyd, a Black man killed while in Minneapolis Police custody in 2020. (The decision was based in fear.)

Some Americans believe that no price is too great to pay to bring reform and equality to the Black community. Others recognize that eliminating evidence from the present doesn’t erase realities from the past.

And still others see product mascots like Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and Mrs. Butterworth (all of whom were based on actual people) not as racial stereotypes, but as icons. They see it as proof that Blacks have always played essential roles in the building of America.

Vera Harris, whose great-aunt, Lillian Richard, traveled the country portraying “Aunt Jemima” for some 20 years, echos the sentiment shared not just by members of the respective families whose ancestors portrayed the famous icon and appeared in print ads, but many other Blacks across the country:

“I understand the images that White America portrayed us years ago. They painted themselves Black and they portrayed that as us. I understand what Quaker Oats is doing because I’m Black and I don’t want a negative image promoted, however, I just don’t want [my great aunt’s] legacy lost, because if her legacy is swept under the rug and washed away, it’s as if she never was a person.

“In spite of our dark past, that past is our past. We can’t run from it, but we can be better in the future. When my grandson is grown and has children, I want them to know that they had a great-great-great aunt that made an honest living, made honest money . . . and was doing what she had to do to survive and make a living.”

Similarly, Larnell Evans Sr., the great-grandson of Anna Short Harrington, the woman who portrayed “Aunt Jemima” after being discovered serving pancakes at the New York State Fair in 1935, believes the re-branding is insulting and unnecessary:

“This comes as a slap in the face. [Anna] worked twenty-five years doing it. She improved their product . . . what they’re trying to do is ludicrous. Twenty-five years of this lady’s life is just going to go away! Why after all this time would they just want to give it up?”

Many feel that should the Aunt Jemima brand somehow survive, it is Nancy Green who should be remembered as the creator of the “Aunt Jemima” character.

References

nytimes.com., “Aunt Jemima Brand to Change Name and Image Over ‘Racial Stereotype’,” Quaker to Change Aunt Jemima Name and Image Over ‘Racial Stereotype’ – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

forbes.com., “Aunt Jemima Gets A New Name After Racism Backlash,” Aunt Jemima Gets A New Name After Racism Backlash (forbes.com)

musejhu.edu., “Aunt Jemima Explained: The Old South, the Absent Mistress, and the Slave in a Box,” (Excerpt), https://muse.jhu.edu/article/423704

syracuse.com., “Exploring Syracuse’s ties to the controversial ‘Aunt Jemima’ brand,” Exploring Syracuse’s ties to the controversial ‘Aunt Jemima’ brand – syracuse.com

nytimes.com., “Aunt Jemima Has a New Name After 131 Years: The Pearl Milling Company,” Aunt Jemima Has a New Name: The Pearl Milling Company – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

nbcnews.com., “Aunt Jemima brand to change name, remove image that Quaker says is ‘based on a racial stereotype’,” Aunt Jemima brand to change name, remove image that Quaker says is ‘based on a racial stereotype’ (nbcnews.com)

webarchive.org., “Book details history of Wallace’s own ‘Aunt Jemima’,” The Cheraw Chronicle – Book details history of Wallace s own Aunt Jemima (archive.org)

scholarworks.iu.edu., Consuming Mammy:A Review Essay on the Manifestations of Mammy . . ., https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2022/3585/5_Consuming+Mammy+V1.pdf?sequence=3