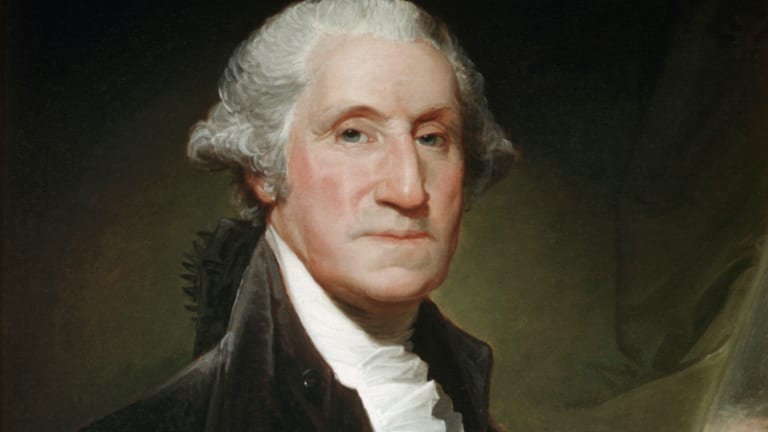

In modern parlance, the name Benedict Arnold is synonymous with treason and betrayal. He’s history’s most famous turncoat.

Though relatively few know the story surrounding Arnold’s condemnation, most are aware that he was accused of leading British forces against the American Continental Army. These were the very forces he’d once commanded.

But what would lead a man to make such a seemingly abrupt about-face?

Early Life

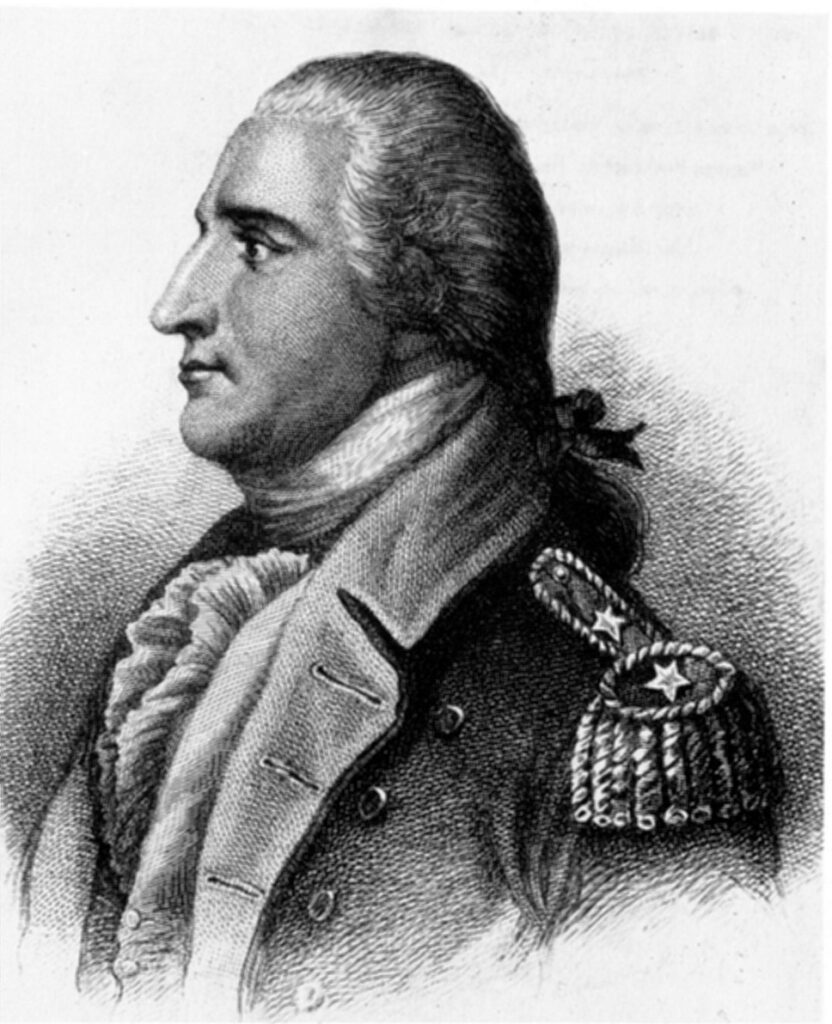

Benedict Arnold was born on January 14, 1741, in Norwich, Connecticut. He was the second of six children born to Benedict Arnold III and Hannah Waterman King. (Three of the six died from yellow fever.)

Like his father and grandfather, Arnold was named after his great-grandfather Benedict Arnold, who was an early governor of the Colony of Rhode Island.

At the time of Arnold’s birth, his father was a successful and wealthy merchant. His family were prominent members of Norwich, Connecticut upper-crust society. But by the time Arnold turned ten, the family fortune was all but gone. His father spent more time at the local tavern than restoring the family business.

His parents managed to send Arnold to private schools in nearby Montville and Canterbury. However, it was apparent that the family’s plans to send Arnold to Yale (where his mother’s family attended) would have to be abandoned.

It was at about this time that Arnold began displaying signs of aggressiveness, overconfidence, and what many termed “cruelty.”

Boyhood

By the time Arnold was 14, he had attended two private schools. Both of them expressed concern over his aggressiveness and lack of self-control. There was also no money for a university education. His father’s failing health prevented him from teaching Arnold the family mercantile business.

With no constraints or responsibilities, Arnold began roaming the Thames River waterfront. He became well-known to the seamen and wharf workers.

More of a means to show off than a genuine interest in seamanship, Arnold learned to rig a ship (said to be able to scale a masthead faster than anyone). He also learned to dive (deeper than anyone else dared), and sail his own single-mast “catboat.”

Though only 5′ 7” tall, he was broad-shouldered and powerfully built. He was quick to demonstrate a handspring, cartwheel, broad jump, or how adeptly he could scale a sail line hand-over-hand. What some characterized as “fiercely competitive,” most described as pure recklessness.

Adolescence

Arnold was constantly running afoul of the law. So his mother secured an apprenticeship for him with two of her cousins, the Lathrops. They were both Yale graduate apothecaries (pharmacists and medical advisors), who operated a successful drugstore and general mercantile in Norwich.

There was considerable hesitation about entrusting Arnold with such an important position. However, the Lathrops had just landed a contract with the Lake George Regional Army to furnish surgical equipment and they were in need of an apprentice.

But in 1758, after only three years as an apprentice, the 17-year-old Arnold slipped away in the middle of the night. He enlisted in the local army unit and joined Captain Reuben Lockwood’s company (on the Connecticut/New York border) to fight the French.

Private Benedict Arnold: Deserter

It is unknown whether Arnold actually participated in military maneuvers at this time. But documents suggest that his mother informed the authorities that her son was underage and did not have her approval to enlist. She later acquiesced.

On March 16, 1759, Arnold re-enlisted (with his mother’s approval), this time in the militia company of Captain James Holmes. According to his military record, the attention-seeking Private Arnold “performed well as the company show-boat.”

He was always trying to impress fellow soldiers with his wrestling or shooting skills, or demonstrating how agilely he could jump over ammunition wagons. But he proved “far less adept at drilling, marching, clearing roads, and following orders.”

After just two months of military life, Private Arnold sneaked out of camp. He made his way home by catching rides with farmers and peddlers. He explained his leaving his unit with tales of a dying mother back home; which was partially true. His mother’s health was deteriorating.

On May 21, 1759, a notice was posted in the New York Gazette. It offered a reward of 40 shillings for the capture and arrest of the deserter, Private Benedict Arnold. Upon reaching home, his mother hid him out for the remainder of the summer.

Arnold’s mother died later that year.

“Dr. Arnold” and the International Trade Game

In the spring of 1760, Arnold signed on as a “supercargo” (an officer in charge of cargo and business dealings) on a ship bound for the West Indies.

Upon returning to Norwich, he quickly became a fixture of the trading establishments of New Haven. He made his way to London, England a short time later–trading in drugs, books, and other merchandise.

On his return trip, Arnold discovered that his father had died. But not before disgracing the family by being arrested multiple times for public drunkenness.

Arnold decided that he’d make his fortune in New Haven. He established business ties with his uncle Oliver Arnold and set up shop as “Dr. Arnold,” He marketed himself as a purveyor of drugs and various merchandise from England.

In 1764, business was prospering. Arnold purchased a number of ships and began to engage in trade with Canada and the West Indies.

He was maintaining his shop, but devoting most of his energies to international trade. But it wasn’t long until he encountered the dark underbelly of commerce: smuggling and pirating.

Like most successful merchants of the time, Arnold, invariably found it far more lucrative to deal in illegal goods, visit illegal ports-of-call, and mingle with smugglers and pirates. Most merchants who dealt in smuggled goods kept their activities under the radar.

But Arnold (who considered smuggling “patriotic”), became increasingly more vocal as to his beliefs and activities. He soon gained a reputation as a leader of the radicals who opposed restrictions imposed by the British.

When local authorities became aware of Arnold’s illegal activities, they threatened arrest if he persisted. Now under scrutiny, few local merchants would do business with him.

Like-Minded Compatriots

Many residents of New Haven, Connecticut found Arnold much too outspoken and reckless. But in certain circles, his rebel/patriot persona was seen as a commendable reaction to British control.

New Haven was becoming more and more polarized regarding Britain’s control over America’s economy. So Arnold’s resistant attitude was something many aspired to support.

Among those was the Free Mason Society. This was a group that boasted of many prominent political figures and statesmen among their ranks. In April of 1765, Arnold was initiated into the New Haven Free Mason Lodge.

Brought into the Fold

Late in 1766, Arnold was introduced to Margaret Mansfield. She was the daughter of New Haven Mason and County High Sheriff, Samuel Mansfield.

The Mansfields were one of New Haven’s most affluent families. They viewed Arnold as a man possessing a fair education, a business certain to expand (once the pesky British issues were resolved), and ambitious and not easily deterred.

Three years his junior (and infinitely more genteel) Margaret (“Peggy”) became Arnold’s first serious relationship. The couple married on February 22, 1767. (She would actually be the first of two Margarets “Peggys” Arnold would wed.)

Though physically frail, Margaret bore Arnold three sons: Benedict (1768), Richard (1769), and Henry (1772). All three sons grew up to become officers in the British Army.

Ever anxious to increase his fortune, Arnold spent little time at home. Instead, he spent weeks at sea, sailing to Canada, the West Indies, New England, and New York.

This is where he developed a reputation for driving hard bargains, ruthlessness on the open sea, and frequently ignoring local social norms. He reportedly shot or killed several men in sword duels for questioning his integrity.

In 1774 (fifteen years after deserting from the Army), Arnold was elected captain of New Haven’s militia. By 1775, at the age of 34, Arnold had amassed a vast fortune. He owned a spacious home, several warehouses, a small fleet of ships, and ran the most profitable apothecary for 50 miles.

That year, Arnold’s first wife, “Peggy” died.

The American Revolutionary War: Siege of Fort Ticonderoga

When the American Revolutionary War (1774 to 1781) began, the Thirteen Colonies had no professional army or navy. Each colony was responsible for forming its own volunteer militia.

In late 1774, news of hostilities at Lexington, Virginia reached New Haven. Newly-elected “Captain” Arnold marched his militia to Cambridge, Massachusetts.

He intended to capture the British-restored Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York. He planned to seize its artillery and then head east to defend other American strongholds.

But when Arnold and his men reached the fort, they discovered that Ethan Allen (noted Connecticut businessman, speculator, and founder of the well-known “Green Mountain Boys” militia) had already been authorized by the State of Connecticut to undertake the very same mission. When Arnold attempted to assert his authority, Allen drew his pistol and stripped Arnold of command at gunpoint.

Humiliated, Arnold took his men and set off to prove he was as great a leader as Allen.

Proving His Worth

Arnold viewed Allen as his biggest obstacle to greatness. He decided to lead his men on a series of military campaigns, with the same reckless abandon he lived his personal life.

He proceeded to seize a flotilla (he christened Liberty). Arnold rigged it with weaponry, men, and provisions. He then ran it to Lake Champlain (bordering Vermont and New York), and seized an important British outpost at St. Jean (at the northern tip of the lake at Quebec).

He then led a charge against the outpost that so “overwhelmed” the British that they ran to their barracks to abandon their weapons. Arnold and his men rushed in, waving sabers. For his resourcefulness and valor, Arnold was promoted to the rank of colonel.

Upon returning to Cambridge, Massachusetts, General George Washington assigned him command of an expedition to the British stronghold Quebec. This route would go via the Maine wilderness.

It required his men to traverse the heavily-wooded, desolate landscape with winter fast approaching. But upon reaching the city, Arnold discovered that it was too well-fortified to wage a successful siege. Even with the aid of General Richard Montgomery’s forces from Montreal.

Though he failed in his mission, Colonel Arnold was promoted to brigadier general (largely because he’d been severely wounded in the attack).

Subsequent Battles

From 1776 to 1781, Arnold fought in battle after battle, both on land and on the water:

- Battle of Valcour Island – He sacrificed 200 men and 11 ships (the battle ended in a draw)

- Battle of Danbury – He led a combined force of 5000 men against 1500 British (for which he was promoted to major-general)

- Siege of Fort Stanwix – (where he defeated British and Native American forces)

- Two Battles of Saratoga – despite being ordered off the battlefield for recklessly endangering his men, he took command of troops on the battlefield and managed to force British troops to retreat; where he was again seriously wounded).

By the end of these campaigns, Arnold had been charged with numerous war crimes. He was relieved and reinstated to duty, and threatened with court-martial. Though his leadership was seen as responsible for deterring British advancement, his actions on and off the battlefield were unbecoming of a military officer.

Even so, in May of 1778, General George Washington placed Major General Arnold in command of Philadelphia.

Court Martial

Once in command of Philadelphia, Arnold began to flaunt his considerable authority. He revealed the first signs of his hidden agenda.

Arnold was fostering Loyalist (American colonists loyal to Great Britain) associations. He conducted business dealings in direct violation of both state and military regulations. These dealings came to the attention of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council.

With no choice but to hold him accountable, the Council referred him to Congress for a court-martial and thorough investigation of his actions. Arnold was charged with 13 counts of misbehavior. These charges included misusing government wagons and illegally buying and selling goods (profiteering).

In December of 1779, Major General Benedict Arnold was found guilty of two lesser charges. He was sentenced to reprimand by General George Washington himself. Believing himself worthy of glory rather than reprimand, in April of 1780, Arnold resigned his command of Philadelphia.

His anger mounting, Arnold began corresponding with British spies about the possibility of changing sides.

Treachery and Treason

Many historians contend that it was Arnold’s belief that he’d been mistreated by the country he’d defended. But documents show that as early as May of 1779, Arnold had already begun making secret visits to British headquarters in New York.

Money was apparently a significant factor in his motivation. When asked to remain in the Continental Army and spy for the British government, Arnold is said to have demanded £10,000–plus the rank of major general in the Royal British Army.

He forwarded intelligence from time to time, but British authorities balked at his demands. Therefore, in October of 1779, Arnold broke off communication. When officially reprimanded by George Washington in December of that year, Arnold resumed correspondence with British officials.

It seems apparent that Arnold intended to betray American interests whether or not the British met his demands.

The previous April, Major General Arnold had been approached by American General Philip Schuyler. This was to discuss the prospect of giving Arnold command of the American fortifications at West Point, New York.

In May, Arnold sent a secret message to British agents informing them of Schuyler’s proposal. He asked for £20,000 to surrender the fort.

On April 8, 1779, the 38-year-old Arnold married 19-year-old Margaret “Peggy” Shippen. She was the daughter of a British Loyalist.

On June 16, 1979, Arnold inspected West Point. He immediately sent a highly detailed report to British General Sir Henry Clinton, explaining the fortress’ weaknesses. Expecting the British to meet his demands, Arnold quietly arranged to sell his home and transfer his assets to London through intermediaries in New York.

On August 3, 1780, Arnold was finally given command of West Point. Almost immediately, he set out to systematically weaken its defenses to make a British siege more likely to succeed.

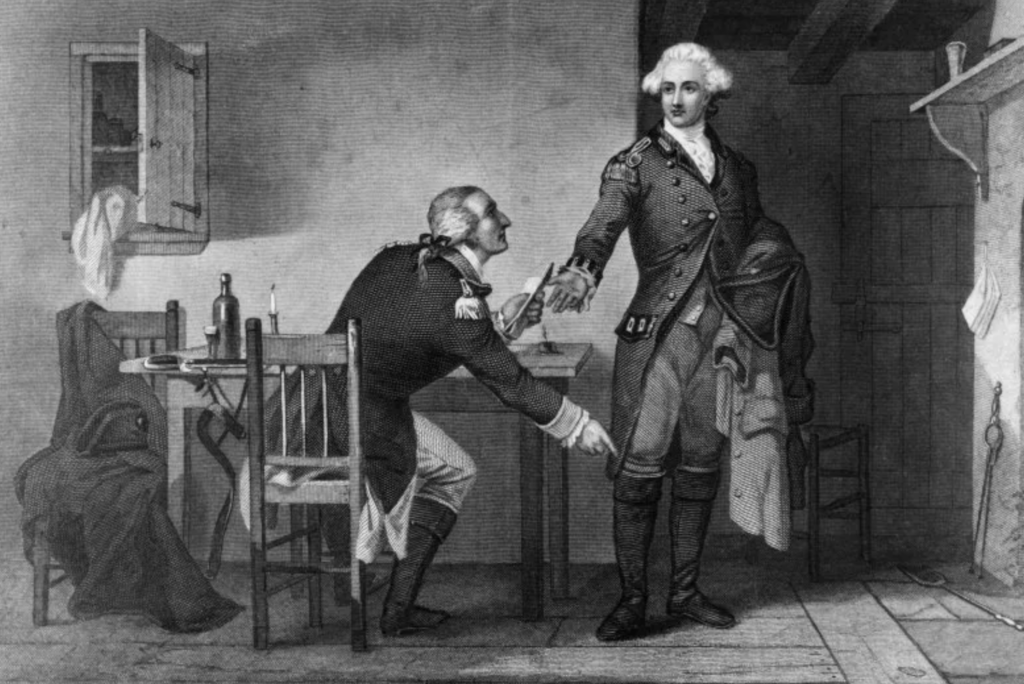

On August 25, Arnold received confirmation of the deal: The British would pay £20,000 if Arnold surrendered West Point. He was to meet with British Intelligence Office Major John André on September 21, 1780, to seal the deal.

The Plot Exposed

Arnold and André met at the home of a British sympathizer named Joshua Smith, on the bank of the Hudson River. The plan was that after the deal was struck, André would escape on his British sloop-of-war the Vulture after nightfall.

But when American forces began firing on the Vulture, André decided to escape over land. Instead, he ran directly into an American militia unit. When they searched him they found six documents detailing how to lay siege to West Point. Five were in Arnold’s own handwriting.

Disgraced: A Man Without a Country

Arnold fled to the safety of British headquarters in New York. He expected to be greeted with the respect and honor the US government had robbed him of. Instead, he found that they didn’t trust him any more than the Americans now did.

When word reached Norwich of Arnold’s treachery, a mob of local citizens stormed Norwich cemetery. They destroyed the gravestones of Benedict senior—and any other marker bearing the same treacherous name—except that of Arnold’s mother.

After the Revolutionary War ended, Arnold escaped to New Brunswick, Canada. There, he reestablished himself as a merchant-shipper.

Normally, brigadier generals in the British Royal Army are entitled to an annual commission of several hundred pounds. But since he had failed to deliver as promised, he was ultimately granted £6,315 for the loss of his property and an annual pension of just £360.

In his final years, Arnold made several trips back to England. He died there on June 14, 1801 at the age of 60; miserable and broken.

References

Flexner, James Thomas. The Traitor and the Spy: Benedict Arnold and John Andre. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1953.

britannica.com., “Benedict Arnold,” Benedict Arnold | Biography, Wife, Meaning, Betrayal, & Facts | Britannica

history.com., “Benedict Arnold is court-martialed,” https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/benedict-arnold-is-court-martialed

Wright, Mike. What They Didn’t Teach You About the American Revolution. Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1999.

gutenberg.org., “Colonel John Brown, of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, the Brave Accuser of Benedict Arnold,” https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/24581

army.upress., “Benedict Arnold, Heroic Traitor,” https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/nco-journal/docs/Heroic-Traitor.pdf