The Carbon County Museum, in Rawlins, Wyoming may never be as famous as the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC, or the Houston Museum of Natural Science in Houston, TX.

But it does have one thing those other museums do not: An “Outlaws” exhibit featuring a pair of shoes made from the skin of the infamous outlaw, “Big Nose” George Parrott.

According to Old West legend, “Big Nose” George (as he was commonly called) was executed on March 22, 1881. This was following a shamefully botched lynching attempt.

Rawlins physician John Osborne had shoes made from the notorious outlaw’s inner thigh skin. He then proceeded to wear the following year to his 1892 inauguration as Wyoming’s governor.

If that isn’t disturbing enough, from 1913 to 1915, when Osborne served as a director for the Rawlins National Bank, he displayed the now-infamous shoes in a glass case in the front lobby as his prized possessions.

But what exactly did “Big Nose” George do to warrant this kind of irreverence?

Who Was “Big Nose” George Parrott?

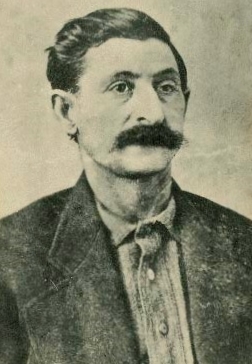

George Parrott, whose true name is believed to have been George Manuse, was an outlaw, highwayman, cattle and horse rustler. He was of some renown and his most striking physical feature was, apparently, a prominent nose.

While few details about his life prior to turning to a life of crime are known, he is believed to have been born on March 20, 1834, in Montbéliard, France. He likely remained a citizen of that country while living in the US.

Apparently, long before drawing attention to himself as an outlaw, “Big Nose” George was busy making a name for himself among a number of small-time highwaymen. They were known for robbing freight wagons and stagecoaches in Dakota Territory, Wyoming, and Montana.

But it wasn’t until the mid-1870s that “Big Nose,” along with one of his more hardened associates, Charlie “Dutch Charley” Burris, decided to make themselves famous.

The Big Train Robbery

In mid-1878, “Big Nose” George, “Dutch Charley,” and four other members of their gang, decided to rob the Union Pacific Continental train. It was passing through Como Bluff, near Medicine Bow, Wyoming. (Legend has it that the train was transporting money for either a bank or the Federal Government.)

Thinking themselves clever, they chose a lonely stretch of railroad track. They undertook to pull out several of the rail spikes and disconnect the iron fish plates (connecting the rails).

They then attached a long telephone wire to the rail. They intended to keep out of sight and pull it away just as the train came along, forcing it off the tracks.

What they hadn’t planned on, however, was the appearance of a “section foreman” named Brown. Brown was walking the tracks making a routine inspection, as was his job. He immediately noticed the missing spikes and dismantled fish plates.

Rather than stop and investigate, he just walked on as if nothing was out of the ordinary. A mile or so down the tracks, Brown turned around and returned to the station. He immediately notified his superiors, thus foiling the accident and robbery.

Now that authorities were aware of a plan to rob the train, they set out to find out who was behind it.

Not knowing how much of the scheme railroad officials had surmised, “Big Nose” George and his gang went on the lam. They rode hard to get away from the scene.

They went through Sand Creek, Four Mile Springs, Seven Mile Springs, and Bloody Lake (on the north side of Fort Alexander, Montana). Then through Rattlesnake Pass, finally choosing Rattlesnake Canyon (near Elk Mountain) as the place they’d hide out.

They were unaware that authorities were hot on their trail and closing in.

The Botched Train Robbery Leads to Murder

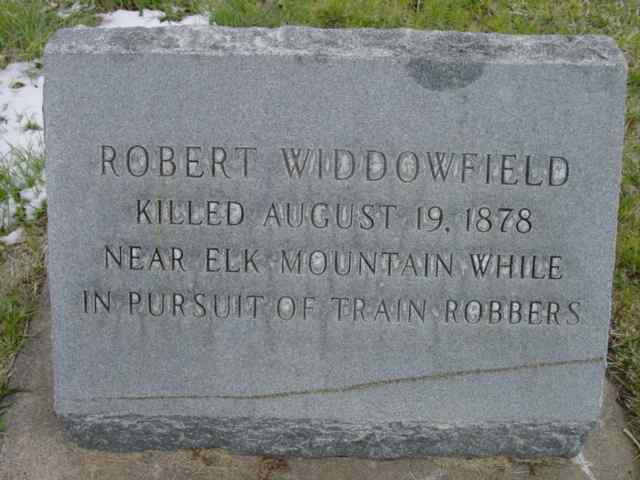

On August 19, 1878, Wyoming deputy sheriff Robert Widdowfield and Union Pacific detective Tip Vincent were commissioned to form a posse. Their goal was to track down “Big Nose” George Parrott’s gang.

A short time later, Widdowfield and Vincent tracked the gang to Rattlesnake Canyon. Unbeknownst to them, a lookout for the gang had spotted them coming. Dousing their campfire, the gang took cover and waited.

When Widdowfield and Vincent arrived at the campsite, Widdowfield realized that the ashes were still hot. But before the posse could react, Parrott’s gang opened fire—shooting Widdowfield in the face.

Vincent tried to make a getaway with the posse but was shot before he made it out of the canyon. The gang took both men’s firearms and one of their horses before hiding the bodies and fleeing the area.

Once the murder of the two lawmen was reported, a $10,000 reward was offered for the “apprehension of their murderers.” (The railroad later doubled the reward to $20,000.)

A Daring Daylight Robbery

In February of 1879, “Big Nose” George, “Dutch Charley” and their gang were in Milestown (now Miles City, Montana) planning the boldest robbery of their careers.

Milestown was a booming and prosperous town. It had become known that a local merchant named Morris Cahn would be taking money back east to restock his business.

To assure his safety, Cahn was traveling with a military paymaster’s wagon train. It consisted of 15 armed soldiers, two Army officers, a covered wagon, and a special “ambulance” transporting Army payroll from Fort Keogh, Montana, to Bismark, Dakota Territory.

At a steep-sided drainage area known locally as a “coulee,” about 10 miles beyond the Powder River Crossing (near present-day Terry, Montana), members of the convoy were forced to take the steep descent at their own pace.

This resulted in the column losing cohesion. The soldiers and wagons became “strung out.” Relying on this eventuality, “Big Nose” George, “Dutch Charley” and the others positioned themselves at the bottom of the coulee, at a turn in the trail where they weren’t visible.

Donning masks, the gang took the convoy by surprise. They easily captured the lead complement of soldiers, as well as the wagon carrying Cahn and the officers.

They then waited for the rear complement of soldiers guarding the money ambulance to catch up. They handily subdued them and robbed them of somewhere between $3,600 and $14,000 (depending on who’s telling the story).

Now “Big Nose” George Parrott was the most wanted outlaw in the territory.

Capture and Sentencing

Flush with cash, “Big Nose” George and “Dutch Charley” split up. They agreed to meet in Miles City to celebrate. Once there, however, the two got drunk and started bragging to a couple of prostitutes about the two Wyoming lawmen they killed.

When word spread that the two “Wanted” outlaws were in their midst, two local deputies, Lem Wilson and Fred Schmalsle, decided to make a name for themselves by apprehending them.

Captured alive, “Big Nose” George was returned to Rawlins, Wyoming to face murder and robbery charges. (Accounts of “Dutch Charley’s” fate vary: one reports that he was lynched before he ever got back to Wyoming.)

On Sept. 13, 1880, “Big Nose” George was arraigned in Rawlins. At this time he informed his lawyer that his real name was George Francis Warden, and that he was born in Dayton, Ohio in April of 1843. (There is no record of his birth in this city.)

Throughout the trial, “Big Nose” changed his plea from guilty to not guilty to guilty again—presumably to confuse jurors. (Which, apparently, didn’t work.)

On April 2, 1881, the jury found “Big Nose” George Parrott guilty of murder and sentenced him to death. (At this time, Wyoming was a “hanging state.”)

Attempted Escape

While waiting to be executed, “Big Nose” George Parrott managed to file the rivets off of his leg irons using a pocket knife and a piece of sandstone. On March 22, 1882, after having successfully removed his shackles, he hid in the washroom until jailer James Rankin entered.

Using the shackles as a bludgeoning weapon, “Big Nose” George struck Rankin on the head, fracturing his skull. While attempting to fight back, Rankin called out to his wife, Rosa, for help. She grabbed a pistol and managed to persuade “Big Nose” to return to his cell under threat of being shot.

When news of the escape attempt spread through Rawlins, a lynch mob of more than 200 citizens surrounded the jail. Donning masks and brandishing pistols, men burst into the jail and held Rankin at gunpoint.

They dragged “Big Nose” George from his cell. Outside, the men surrendered the outlaw to the mob intent on “stringing him up.”

They replaced the shackles on his ankles to make it harder for him to resist.

A Lynching Gone Wrong

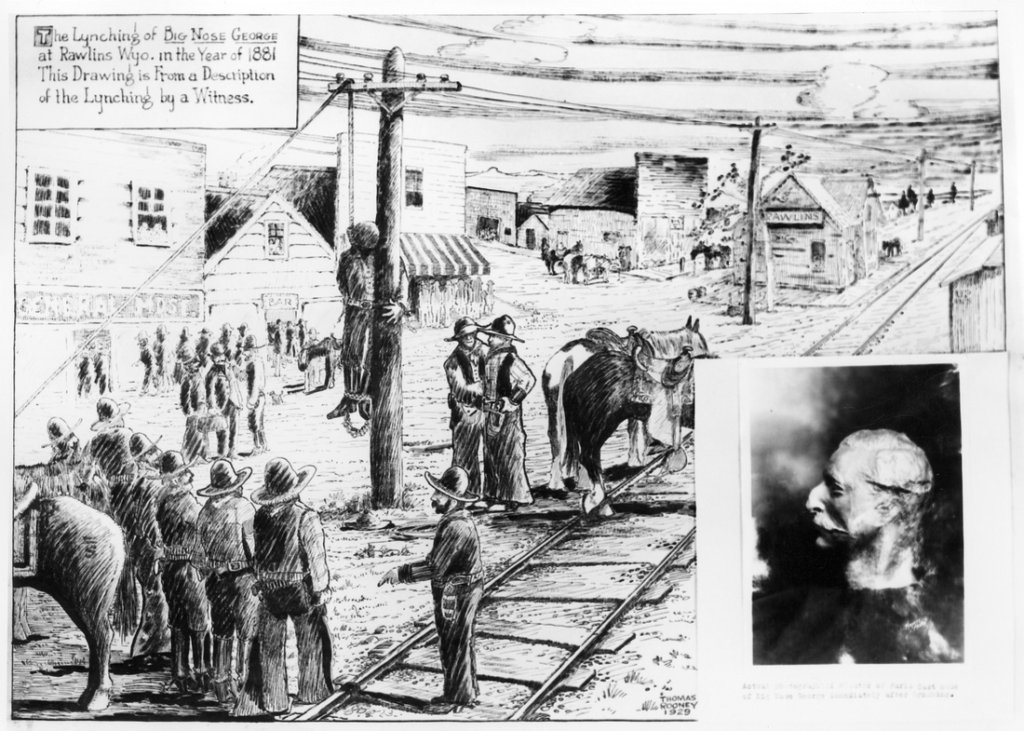

Tying “Big Nose” George’s hands behind his back, the lynchers slipped a noose around his neck. They forced him to stand on an empty kerosene barrel, then tossed the rope over the crossbar of a telegraph pole. Once in position, he was prodded to jump—but the rope broke.

Now becoming a formal hanging, the mob replaced the noose. But this time, they made him climb a 12-foot ladder leaned against the telegraph pole.

When the ladder was pulled away, “Big Nose” managed to free his hands and cling to the pole. He started begging for someone to take mercy and shoot him but no one would.

When he could no longer hold on, “Big Nose ” George Parrott let go. He was strangled to death by the rope before the crowd of 200 gathered to bear witness to his demise.

Among the witnesses was Rawlins physician John Osborne, who’d been asked to attend the hanging to certify that the notorious outlaw was dead.

Undignified Aftermath

With no kin to claim the body, Dr. Osborne decided that “Big Nose” George Parrott’s body would best serve medical study purposes. (By some accounts, Union Pacific Railroad surgeon Dr. Thomas Maghee, as well as his medical protégé, Lillian Heath, were also present for the decision.)

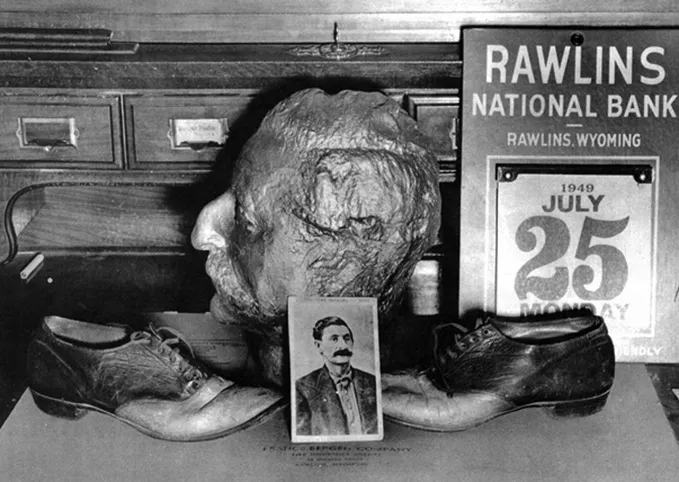

The first thing Osborne did was make a death mask of the notorious outlaw. This was thought to be the only such mask ever created for an Old West outlaw. (The mask is currently on display in the Carbon County Museum, in Rawlins, Wyoming.)

Osborne then skinned the body. He was intent on sending the thigh flesh to a tannery in Denver, Colorado with instructions to make him a pair of two-tone shoes and a medicine bag. (Which he apparently did.)

Next, Osborne (perhaps assisted by Maghee and Heath) sawed “Big Nose” George’s skull into two halves. They wanted to see if his brain was visibly different from a normal brain. (Apparently, it wasn’t.)

By some means, the top half of the skull came into the possession of Dr. Maghee, which he reportedly gave to Lillian Heath (who later became Wyoming’s first female physician).

Lastly, when the body could provide no further insight nor entertainment, the lower half of “Big Nose” George’s skull was placed in a whiskey barrel filled with saline. The rest of the outlaw’s bones were subsequently buried several years later. They remained untouched for more than half a century.

End of the Old West Saga

The story of “Big Nose” George Parrott had all but faded from memory until May 11, 1950. It was then that construction workers unearthed a whiskey barrel filled with bones while working on the Rawlins National Bank on Cedar Street, in Rawlins, Wyoming.

Inside the barrel was the bottom half of a skull, a bottle of vegetable compound, and the shoes said to have been made from the flesh of “Big Nose” George’s thighs.

Dr. Lillian Heath (Dr. Thomas Maghee’s former protégé), now in her 80s, was contacted. She graciously agreed to provide the skull cap for comparison. It proved to be a perfect match.

DNA testing later confirmed that the remains were indeed those of “Big Nose” George Parrott.

For History Buffs

Today, the two-tone shoes made from the skin of “Big Nose” George Parrott are on permanent display. They are at the Carbon County Museum in Rawlins, Montana, along with Parrott’s death mask and the bottom half of the outlaw’s skull.

The shackles used to re-secure the outlaw during the botched lynching/hanging, as well as the top of the skull, are said to be on display at the Union Pacific Museum in Council Bluffs, Iowa.

The famous medical bag made from “Big Nose” George’s skin has never been found and is suspected to be in a private collection somewhere.

References:

web.archive.org., “The Hanging of Dutch Charley and Big Nose George, the Election of John E. Osborne,” https://web.archive.org/web/20090405032307/http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/rawlinsa.html

wyohistory.org., “John Osborne,” https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/john-osborne

allthatsinteresting.com., “Meet Big Nose George, The Wild West Outlaw Who Was Killed And Turned Into Shoes,” Meet Big Nose George, The Wild West Outlaw Who Was Killed And Turned Into Shoes (allthatsinteresting.com)

findagrave.com., “Charlie ‘Dutch Charley’ Burris,” https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/113556618/charlie-burris

truewestmagazine.com., “Big Nose George Parrott,” https://truewestmagazine.com/article/big-nose-george-parrot/

carboncountymuseum.org., “CURRENT EXHIBITS,” Carbon County Museum Current Exhibits

legendsofamerica.com., “Big Nose George Becomes a Pair of Shoes,” Big Nose George Becomes a Pair of Shoes – Legends of America