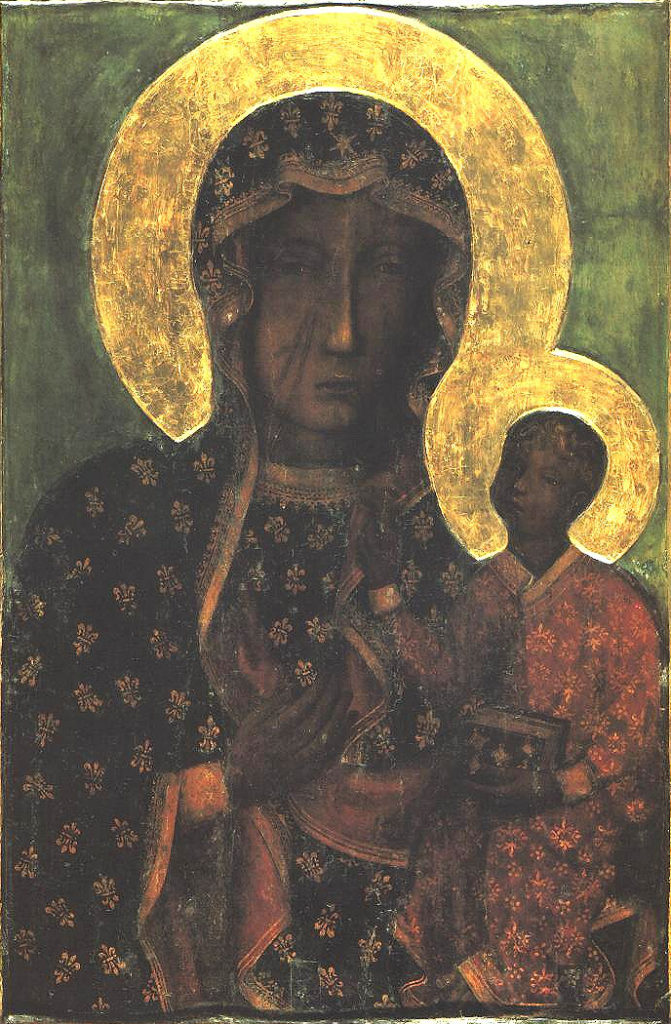

At the monastery of Jasna Gora in Częstochowa in Poland today, there is a revered icon of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It has been housed there for some time, but its history is shrouded in legend.

The image is of Mary holding Jesus. It is believed, at least in Christian lore, to have been originally painted by St Luke the Evangelist, producer of one of the four canonical gospels of the life of Jesus.

The icon is said to have been housed in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, throughout most of the medieval period, before being brought to Poland in the fourteenth century for safe keeping as the Ottoman Empire threatened Constantinople.

It was soon deposited at the monastery near Częstochowa. It was believed to have been responsible for many miracles, not least the holding off of an army of 4,000 Swedes by just a few hundred Polish defenders when the monastery was attacked in 1655 during the Second Northern War.

As a result, in 1717, Pope Clement XI issued a canonical coronation on the icon, effectively recognizing it as a saintly relic. So today, Our Lady of Częstochowa has been issued three different golden roses by three different Popes, symbols of the reverence with which the Papacy holds an object.

But what is extremely unusual about this is that Our Lady of Częstochowa is a Black Madonna, in which Mary and Jesus are also depicted as black.

The Prevalence of Black Madonnas

Perhaps we shouldn’t be so surprised that Our Lady of Częstochowa is a Black Madonna. After all, there are surprisingly more examples of these today than one would think for a religion that has typically depicted Jesus, Mary, and every other Biblical character as being decidedly white.

For instance, there are over 500 examples of Black Madonnas in Europe today. Over 150 of these are located in churches, monasteries, galleries, and other locations in southern France alone. And these are not modern depictions of Mary, which seek to be more inclusive.

Instead, the Black Madonnas generally date to the medieval period between 500 and 1500. In the cathedral at Chartres, south of Paris, there are two Black Madonnas alone, one dating to 1508 and the other admittedly being a replica of an original which was destroyed at the time of the French Revolution.

Another famed example is to be found at the monastery of Montserrat near Barcelona in Spain. This again depicts Mary and Jesus as being black, but it is in the shape of a statue rather than a painting.

This Black Madonna is believed to have originated in the Holy Land during the Crusades and to have been brought to Catalonia in the thirteenth century.

The Controversy Surrounding Black Madonnas

Inevitably these Black Madonnas have created a large amount of controversy and debate. Many have wondered why so many images of Mary and Jesus appear this way in a religion that has not been accommodating towards non-white people for much of its existence.

On several occasions during the late medieval and early modern periods, Popes were at best lukewarm about whether or not black people even had souls that could be saved.

In addition, the Papacy divided the world into respective Spanish and Portuguese jurisdictions with the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. Catholic Portugal received Brazil as a result and, over the next three centuries, transported over six million black Africans here as slaves, over fifteen times the amount which was taken to North America by the British.

Thus, there are clear reasons why people find the proliferation of Black Madonnas during the medieval and early modern periods downright confusing and controversial.

Explanations for the Black Madonnas

Numerous theories have been put forward to explain why so many Black Madonnas were produced and are extant today. Firstly, scholars note that many of these were produced in regions outside of the jurisdictions of the Roman Catholic Church, where Christianity has always had a tradition of being less white, so to speak.

For instance, the Greek Orthodox Church had its roots in the early Christian church of the Eastern Mediterranean, where people were darker-skinned in the days of Jesus.

Similarly, the Coptic Church, which developed in Egypt in late antiquity extended into Ethiopia and survived there, even beyond the Arab conquest of Egypt in the seventh century.

Many Black Madonnas, including Our Lady of Częstochowa in Poland, come from this tradition of non-white iconography in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Horn of Africa.

It is also inevitably the case that some of the Black Madonnas have changed color over time, whether on account of the material used changing tone or candle smoke affecting the image.

For instance, lead-based pigments used in paintings can change color significantly over the decades and centuries. Similarly, statues of the Madonna are often placed right next to where votive candles are lit, so hundreds of years of having lit candles and smoke next to them could theoretically have changed the color of these statues.

Another major theory holds that the Black Madonnas are explained by the residual influence of Pagan belief in the earth goddess in medieval Europe.

Such earth goddesses, such as Isis in Egypt, Artemis in Greece, or Ceres in the Roman belief system, were often depicted as being dark-skinned, in the case of Isis because of her origins in North Africa and in the case of others because black, volcanic soil is so fertile.

The worship of Mary, the apostles, and the cult of saints effectively replaced the wider polytheistic pantheon of the Pagan religions during the early medieval period, so the idea here is that the Virgin Mary was perceived to be synonymous with the earth goddess.

One gave birth to Jesus, while the other gave birth to life from the soil. All of these explanations have some things to support them, but other aspects seem more difficult to explain away. What is for sure is that the controversy of the Black Madonnas will no doubt be further explored in years to come.