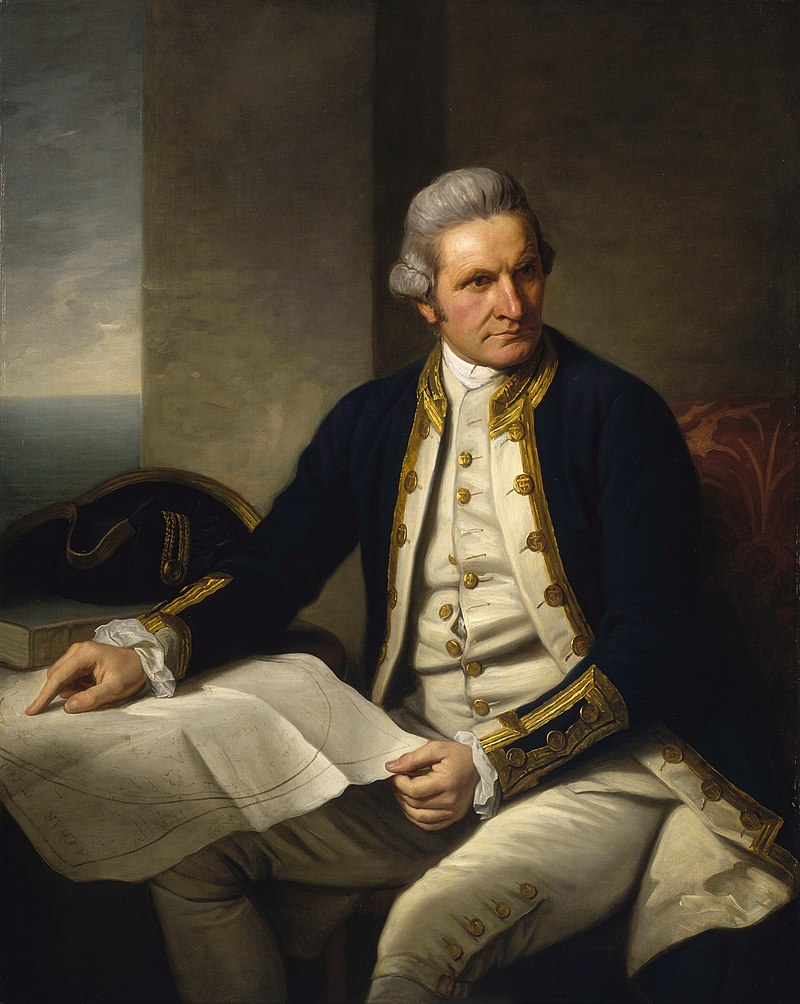

James Cook (1728 – 1779) was a British naval officer, navigator, explorer, and cartographer. He is mainly known for his expeditions between 1768 and 1779 to the Pacific Ocean, New Zealand, and Australia. Though he was a well-decorated member of the British armed forces, his professional life was far from perfect, and very little is known of his personal life.

A much-debated character in history, his life is as topsy-turvy as they come. There is much to admire and loathe, just like the many historical figures we study today. Let’s look at his life—the good, the bad, and everything in between.

Cook’s Early Life

James Cook was born in Yorkshire to a farmhand migrant from Scotland. He had seven siblings. Five of them died early, leaving behind two sisters, Christiana and Margaret. From an early age, Cook showed great potential, prompting his father’s employer to pay for Cook’s education. Cook spent most of his teenage years working on the farm and was later employed at a general store in Whitby. The store’s coastal location introduced him to ships and the sea.

By the time he was 18, Cook was an apprentice to a well-known Quaker shipowner. At 21, he was rated an able seaman. During the off-season, Cook lived ashore and studied mathematics. In 1752, he was promoted to mate. Cook then volunteered as an able seaman in the Royal Navy as he thought it would be an interesting and rewarding career.

His striking features and ability to handle challenges made him rise in the ranks almost instantly, advancing to master’s mate and boatswain. He was also given command of a captured French ship during the Seven Years’ War. In addition, he is credited for charting the St. Lawrence River.

His Voyages

In 1768, the first scientific expedition to the Pacific was organized and Cook was appointed commander. He was to convey members of the Royal Society to Tahiti so they could observe Venus travel across the Sun. The following year, he ventured further south in search of Terra Australis (now Australia).

Sailing from Tahiti, Cook found and chartered New Zealand for six months. He navigated around Cape Horn, eventually landing on the southeast coast of Australia where he surveyed the coast and navigated Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef. It was a challenging feat considering the ship and the available equipment on deck.

Cook also carried out secret orders where he was asked to seek out the “Great Southern Continent.” Naturally, he followed orders and sailed south but found no evidence of the fabled continent. However, during this journey, he proved that New Zealand was a pair of islands instead of one large landmass.

Upon his return to England, Cook was promoted to commander. Not long after, he organized another voyage. Inspired by Joseph Banks, he took two ships to circumnavigate and venture into the Antarctic. By 1775, Cook was still unsuccessful in finding Terra Australis though he had navigated the Antarctic, Tonga, and Easter Island.

He proved that “Terra Australis” was a landmass of Australia and New Zealand. After he got back, he was promoted to captain. He was also awarded the gold Copley Medal, one of the highest honors, for his research paper on scurvy.

In 1776, Cook embarked on an adventure that led to his discovery of the Pacific’s well-kept secret: a northwest passage around Canada and Alaska or a northeast one around Siberia. Although he was unsuccessful and the trip marked the beginning of the end, he changed the world map, bringing it significantly closer to how it is today.

Scurvy Onboard

Scurvy, a dietary disease caused by the lack of vitamin C, was quite prevalent among seafaring folks in the 18th century. Storing and procuring fresh fruits and vegetables was challenging onboard, forcing crews to predominantly rely on processed meats and grains.

Cook first encountered scurvy in 1756 when he rejoined H.M.S. Eagle at Plymouth. During this voyage, approximately 130 men became extremely ill and were hospitalized while 22 died. Over the years, he learned more about the condition.

During his voyages, Cook was a notorious advocate for cleanliness. He insisted on proper ventilation in the crew’s quarters and a diet rich in vitamin C through foods like cress, and sauerkraut. He also encouraged sailors to consume fresh fruits whenever they were on land to prevent scurvy. On some voyages, there were no fatalities from the illness because of his efforts.

Cook was also promoted to captain for his bravery. The Royal Society awarded him a gold Copley Medal for his efforts in preventing scurvy and his paper detailing his observations and the disease’s preventive measures.

His Personal Life

By 1762, Cook was 33 years old. He returned to London where he married Elizabeth Batts, a young woman of his acquaintance. Since he was always at sea, his personal life was rather nonexistent.

Cook and Batts had six children. Unfortunately, three died in infancy while the other three had died by 1794. Like their father, 2 of his three sons joined the navy before their deaths.

Batt and Cook often exchanged letters. However, not much can be gathered from their personal conversations. All of Cook’s entries read like ledger entries, crisp and to the point. In one of his entries, he wrote, “Most part of these 24 hours Cloudy, with frequent Showers of Rainone.”

As for Elizabeth, she died at the age of 92, surviving her partner by 56 years. At the time of Batt’s demise, she left money to nearly 50 people, including Cook’s nephews, nieces, and their families. A great deal of her funds were donated to various charities, including the Minister and Churchwardens of St Andrew’s Church in Cambridge, the Widows of Clapham, the Royal Maternity Charity, and the School for the Indigent Blind.

For some reason, she burned all her correspondence between her and her husband, leaving historians with little to no information.

The End of the Beginning

In 1776, Cook left for this third and last sea voyage. He was on a mission to find the North-West Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Britain and Cook believed that this passage would open new trade routes while allowing them to avoid the passage through the capes.

On his final expedition, Captain Cook took two ships: the Resolution and Discovery. In 1778, his crew spotted an island along the Northwest Coast of America, which would later become Oahu and Kauai in Hawaii. They anchored their ships at the coast of Kauai, marking the beginning of the end for Captain Cook.

Upon their arrival, the people addressed Cook as “Orono” or “Lono,” a prestigious title akin to a god. Locals greeted the explorers with elaborate gestures. Cook and his crew played along and explored the island, learning about the indigenous people’s religion, crops, and more. After their warm reception, Cook eventually went on his way to discover the Northwest Passage.

In 1779, nearly a year later, Cook went back to the islands. Once more, the islanders treated Cook and his crew with hospitality, plying them with food and gifts. However, this arrangement, which greatly favored the Englishmen, didn’t last. After some time, the crew overstayed their welcome and their needs surpassed the island’s resources, causing a rift between them and the islanders. This eventually forced Cook and his crew to leave.

As they tried to sail away, rough seas damaged Cook’s ships, forcing them to return to the island. Unlike their previous visits, the locals did not welcome them. They even stole items from the ships, including a longboat and iron pieces. After experiencing similar hostility in Tahiti, Cook thought it best to take matters into his own hands.

The crew kidnapped one of their most powerful chiefs, Kalaniopu’u, and held him hostage in exchange for the stolen items. Together with his crew, Cook also burned down villages in an attempt to get back what was theirs, adding to the villagers’ sense of loss and hostility. During one altercation, the inhabitants, who felt threatened and alarmed, stabbed Cook and killed a few of his crew. Cook was killed on February 14, 1779, in Hawaii, leaving behind his wife.

Despite the nature of his death, many believe that the locals applied salt on his body to preserve it, dismembered his corpse, burned it, and cleaned up his bones. This was a ritual reserved for kings.

After his death, Captain Clerke led the ships back home. However, he died on the voyage, leaving Lieutenant Gore to command the ships home. Upon reaching England, they delivered the news of Captain James Cook’s demise.

Cook’s Ruthlessness

There’s no denying that Captain Cook played a vital part in Britain’s history and the world’s maps as we know it. While he was a well-decorated British naval officer, his darker side is often overlooked.

It is well known that he mistreated the indigenous people of Hawaii by exploiting their resources, wreaking havoc on their villages, and abducting their leader to assert dominance. However, this was not the only time when Cook displayed his ruthlessness.

Britain’s compulsion to colonize every country it explored is enough to explain why Cook invaded other countries when “exploring new routes.” Some say that despite orders to win over “the consent of the natives,” Cook did no such thing. In fact, it was noted that he instantly killed the first groups of indigenous people he laid eyes on. Their warnings not to come ashore were often ignored. Cook even held on to the spears thrown at him and they are still displayed in the British Museum today.

Cook also repeatedly ignored commands from his superiors because he wanted to explore and map out the areas he explored. He conquered and invaded them, helping the British Empire grow its long list of colonies.

Historian John Maynard documented Cook’s prowess in invading new territories. Maynard described him by writing, “he represents white Australia in all of its guises including invasion, occupation, dispossession and the conducting of a symphony of violence.”

Nicholas Thomas, an academic who wrote Cook’s biography, explained, “Tongans were subjected to two, three and even six dozen lashes… the ears of some thieves were cut off, and one man’s arms were cut with crosses through to the bone, to mark him out permanently, and to horrify and deter others.”

In addition to these accounts, Cook also documented some of the atrocities he doled out to his own crew in his journal entries. One of them reads, “Punished Richard Hutchins, seaman, with 12 lashes for disobeying commands.”

Captain Cook: A Man Who Dedicated His Life to Exploration

Cook’s explorations and findings as a naval officer, cartographer, and explorer remain important in the discovery of the masses of land as we know it. His abilities, determination, and sensibilities in leading successful voyages were unmatched. However, they also came at a steep price that was often marked by violence. Despite his honorable achievements, he was a character with serious flaws that are hard to dismiss.

Although his personal life was not as glorious, he was a leader on deck, having saved the lives of several crew members. He spent most of his married life away at sea to navigate unknown waters, explore various lands, and understand foreign cultures. He also closely studied scurvy and prevented it from spreading by implementing strict hygiene standards onboard and encouraging the consumption of vitamin C among his crew.

Captain Cook was a man of discipline and ambition, going above and beyond with every assignment. Although his treatment of indigenous people and his crew is highly debated, he remains one of Britain’s most beloved historical figures.

Despite the atrocities he brought onto the Hawaiians and his brutal death, his corpse was ritualistically prepared as if he were a king. Locals supposedly used sea salt to preserve his hands before roasting the rest of his corpse in a pit and cleaning his bones. He was no king but he was bestowed a royal send-off by the islanders even after conflict erupted. Though he had many negative qualities, his strength, rigor, and bravery remain unquestioned.