Last updated on March 1st, 2023 at 05:00 pm

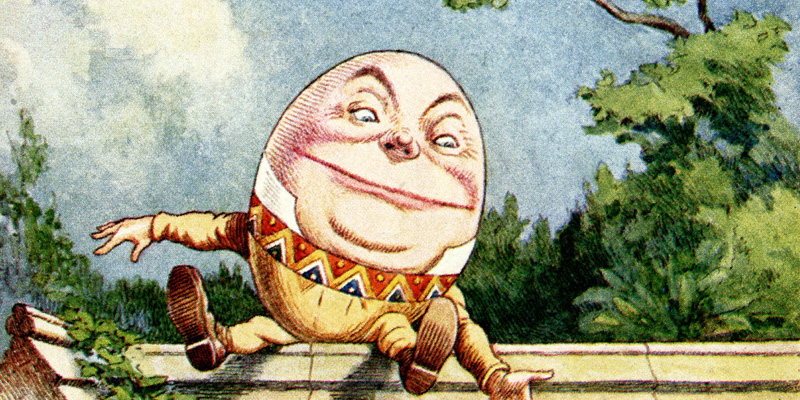

Writing in 1843 in his collection of eighteen essays compiled and entitled as Celebrated Crimes, the great French novelist, Alexandre Dumas, made a startling claim about modern depictions of Jesus Christ.

Dumas claimed that all modern depictions made of the great Jewish prophet and the Christian son of god stemmed from pictures of one individual.

That person, the author of such masterpieces as The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo stated, was one Cesare Borgia, a fifteenth-century Italian cardinal and the son of Pope Alexander VI.

There is indeed a striking similarity between Borgia, as he appears in several portraits that have survived him, and the modern image of Jesus. But is this just pure coincidence, or was there some merit to Dumas’s claim? Here we examine the Frenchman’s hypothesis.

Who Was Cesare Borgia?

Everyone knows who Jesus Christ was, but who exactly was Cesare Borgia? Though little known to most modern people, Borgia was one of the most infamous political figures of Renaissance Italy.

He was born on the 13th of September 1475 at Subiaco near Rome and was the son of Cardinal Roderic Borgia and his Italian mistress Vannozza dei Cattanei, and brother to the black widow of Rome, Lucretia Borgia.

In 1492 the notoriously corrupt Cardinal Roderic Borgia was elevated to the Papal tiara and became Pope Alexander III, a position he would hold until his death in 1503.

As the head of the Papal States in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, Alexander ruled over a temporal state, one which controlled most of central Italy, including the province of Lazio south towards Naples.

Italy was heavily divided at the time between competing city-states such as Florence, Milan, Urbino, Genoa and Venice.

Moreover, this was a time of war as right around the time of Alexander’s accession Spain and France had become involved here to try to establish their dominance over the peninsula. The Italian Wars, which were driven by the two powers, would last for sixty years.

Cesare was soon involved in these machinations. On his elevation to the Papal office in 1492, his father made him a cardinal, despite only being a teenager, but in the years that followed, Cesare fashioned himself into a military commander.

He successfully expanded the Papal States during his father’s papacy and carved out his own principality in central Italy in the Emilia Romagna area north of Rome towards Bologna.

Additionally, as part of an alliance with the French, he was involved in the occupation of Milan and Naples, bringing the Papal States’ temporal power in Italy to its highest point. He was rightfully acclaimed for his shrewd diplomacy and military abilities.

Indeed, so infamous was Cesare in these respects that he heavily influenced Nicoló Machiavelli when the great Florentine political theorist came to writing his satirical guidebook for a ruthless ruler, The Prince, in the early 1510s.

However, his career was to prove short-lived. Borgia’s power was greatly reduced following his father’s death in 1503, and having relocated to Spain, he was killed in an ambush in 1507 in the north of the country at just thirty-one years of age.

Was the modern Jesus based on Cesare Borgia?

So, it is clear that Cesare Borgia was a key figure in the political machinations of Italy during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century. Is there any truth to Dumas’s contention that the portraiture of Jesus Christ changed during the sixteenth century to reflect portraits of Borgia?

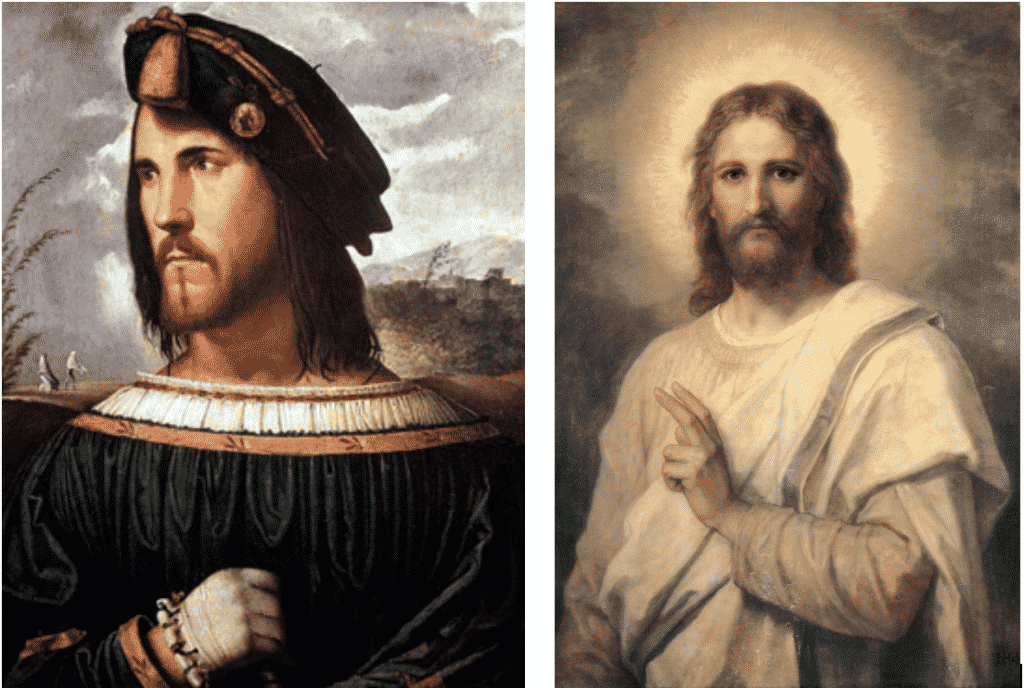

Suppose one places copies of the stereotypical Jesus next to a portrait of Borgia, such as that produced by the northern Italian painter Altobello Melone. In that case, one will indeed see a striking similarity between the pair.

Both are generally of a healthy weight, without excessive facial fat. Both have medium-length beards and mustaches and similar skin tones.

Both are also possessed of intelligent and paradoxically (in Borgia’s case) somewhat sympathetic gazes. One can see why Dumas might have made the assertion that he did.

Yet, there is no truth to his claim. For Dumas’s statement to be accurate, we would need more than a similarity between how Borgia was painted and how Jesus Christ was depicted since the early sixteenth century.

We would need to see a discernible shift in how Jesus was being depicted around the time that Borgia was alive or shortly after that.

For instance, if Jesus was depicted as the darker-skinned, smaller individual that he almost certainly would have been in real life, prior to Borgia’s portraits entering the frame, then there would be a link.

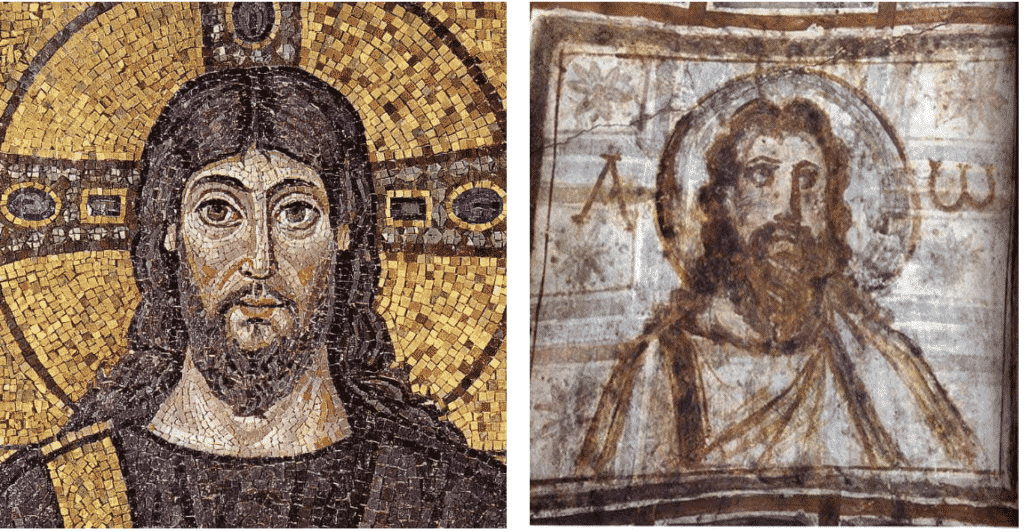

Yet this is not the case. There is clear and completely unequivocal evidence that Jesus Christ was already being depicted in this way for centuries prior to Borgia’s life and the appearance of portraits of the Italian politician.

Such images of the bearded, modern-day Jesus can be found from all over Europe, but we will take just two early examples here to illustrate the point. The first comes from the Catacomb of Commodilla on the Via Ostiensis in Rome.

Here there is a mural containing an image of a bearded Jesus, which is believed to be one of the earliest examples of the modern-day stereotypical image of the prophet. It dates to sometime in the fourth century and so pre-dates Borgia’s life by about 1100 years.

The second example dates from the early sixth century. At the time, the emperor of the Eastern European Empire or Byzantine Empire, Justinian I, succeeded in reconquering some of the Western Roman Empire, mainly in Italy and North Africa.

A building program followed, and this included the Basilica of San Vitale in the town of Ravenna in northern Italy.

This is a UNESCO World Heritage site today and contains a famous series of mosaics depicting biblical scenes, early Christian figures, and contemporary political figures, including the emperor Justinian and his wife, Theodora.

One of these panels very clear shows Jesus Christ. Here he is yet again depicted in the typical manner in which he is portrayed in modern times. The Ravenna Mosaics pre-date Cesare Borgia’s life by nearly a thousand years.

Dozens of other examples from throughout the Middle Ages could be cited to demonstrate that Jesus was depicted in this way for hundreds of years before any portraits of Cesare Borgia in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century.

As such, while Dumas presented an interesting story, one which had a particular point of interest in the contrast of the saintly Jesus and the ruthless, Machiavellian Borgia, it was nothing more than a story, and there is no truth to his claim that portraits of Borgia impacted on how western society depicted Jesus Christ from the sixteenth century onwards.

Sources

Michael Ross, Alexandre Dumas (London, 1981).

For earlier studies of Borgia in English, see William Harrison Woodward, Cesare Borgia: A Biography (New York, 1913); Carlo Beuf, Cesare Borgia: The Machiavellian Prince (London, 1942); Sarah Bradford, Cesare Borgia: His Life and Times (New York, 1976).

John Scott and Vickie B. Sullivan, ‘Patricide and the plot of The Prince: Cesare Borgia and Machiavelli’s Italy’, in The American Political Science Review, Vol. 88, No. 4 (December, 1994), pp. 887–900.

James Stevenson, The Catacombs: Rediscovered Monuments of Early Christianity (London, 1978). Jerome Kiely, ‘The Ravenna Mosaics’, in The Furrow, Vol. 5, No. 6 (June, 1954), pp. 373-376; Stuart Cristo, ‘The Art of Ravenna in Late Antiquity’, in The Classical Journal, Vol. 70, No. 3 (February – March, 1975), pp. 17–29; Sarah E. Bassett, ‘Style and Meaning in the Imperial Panels at San Vitale’, in Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 29, No. 57 (2008), pp. 49–57.