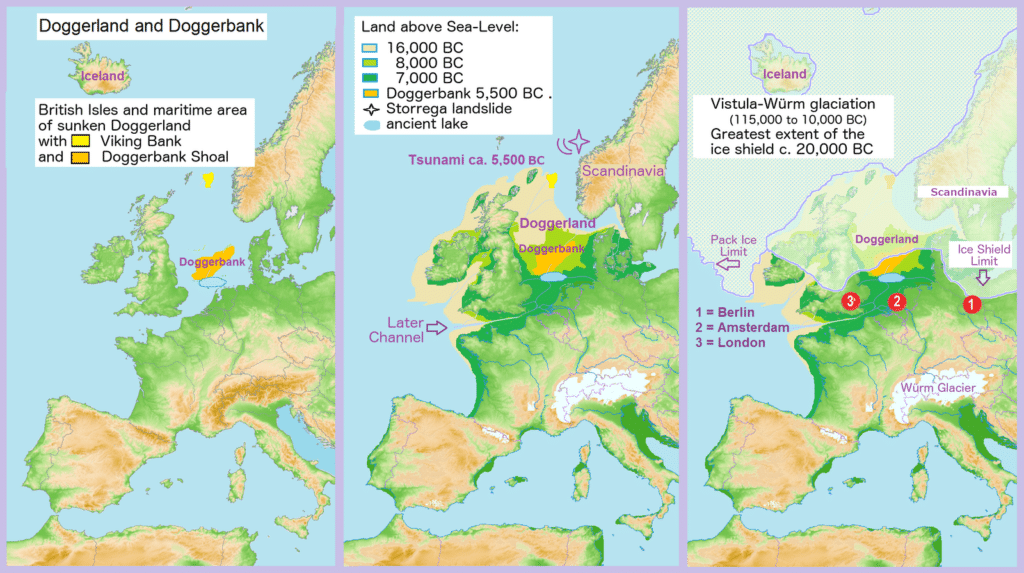

Nine thousand years ago, the British Isles were connected to each other and to the mainland by vast stretches of low-lying lands. These lands were collectively referred to as Doggerland.

At its height, this vast area made up a quarter of European land. It provided rich hunting grounds for countless generations of hominids, including prehistoric humans.

The area was permanently flooded over eight thousand years ago, and that once-dry land that now lies beneath the water is called the Dogger Littoral.

How Doggerland Got Its Name

The name comes from Dogger Bank, a shallow area in the North Sea that once made up the northernmost hills of Doggerland.

Its Dutch name, Doggerbank, is essentially the same. The area was rich in cod, which was commonly called dogge in Dutch at the time.

Doggers were a type of fishing boat common in the North Sea starting in the fourteenth century. They remained in use for centuries, evolving from a single-masted form to a double-masted version. The fishermen aboard caught cod with rods and fishing lines.

These days, the area is being converted to a wind farm. Dogger Bank Wind Farm began producing electricity in October of 2023, and additional units are still under construction. When complete, the wind farm has the potential to provide electricity for six million homes.

Doggerland in the Ice Age

During the Last Glacial Maximum, the North Sea and much of Northern Europe were covered in sheets of ice. It covered most of the British Isles and also the northernmost hills of Doggerland.

The world began to warm up around fourteen thousand years ago. The ice receded, leaving a huge lake behind in the central part of Doggerland. A wide, slow-moving river ran down the English Channel.

Doggerland became a low-lying tundra populated by mammoths and a few intrepid humans.

Mesolithic Doggerland

By 10,000 BC Doggerland was covered by rich ecosystems that included salt marshes, lagoons, mudflats, streams, rivers, lakes, and freshwater marshes. These places provided hunter-gatherers with all of the game and materials that they would have needed.

Doggerland made up about one-fourth of the land in Europe. Vast grasslands and forests stretched from France to Scandinavia.

Studying Doggerland

Archeologists have been studying Doggerland since the late 19th century. By the early 20th century, they had found animal remains and flint tools.

In 1931, a barbed antler point crafted to catch fish was discovered in a hunk of peat brought up by a trawler. It was somewhere between six and twelve thousand years old. The barbed point is over eight inches long and was probably used as a harpoon or eel spear.

When a group of Cambridge academics studied the peat in which the harpoon had been discovered, they realized that the harpoon had been used in a freshwater environment. They realized that this indicated the existence of a great plain stretching across what was now the North Sea.

Prehistoric archeologist Bryony Coles dubbed the area Doggerland in the 1990s. She produced some of the first maps showing what the area might have looked like all those thousands of years ago.

Modern archeologists and geologists have used data gathered by oil and gas companies to map out the ancient hills, valleys, riverbeds, and coastlines of Doggerland.

In May of 2019, an archeological survey found solid evidence of civilization in Doggerland. The RV Belgica, a joint Belgian-British vessel, found a stone-age hand tool on the seabed of the North Sea. That same year, another team of scientists found a hammerstone flint.

Other ancient artifacts have been found in sand dredged from the bottom of the North Sea and deposited along beaches in the Netherlands as a coastal protection measure.

Marine geoarchaeologists use sediment core samples taken from the ocean floor to learn more about Doggerland. A one-meter sample can provide them with between five and ten thousand years worth of information.

In some samples, tree bark gives way to shells, painting a picture of a gradually rising sea.

Ancient History

Long before homo sapiens arrived in Europe, other hominids traversed Doggerland.

The oldest footprints ever found were discovered in Norfolk in 2013. They came from five people, both adults and children, who lived over 800,000 years ago. They may have been homo antecessors, who were closely related to both modern humans and Neanderthals.

Hominids came to Doggerland again and again during warmer periods. They would have hunted the wooly rhinos and mammoths that flourished there in addition to feasting on eggs, birds, and marine life.

Rich flint deposits provided them with material for weapons, and marshland reeds were probably used to make baskets and shelters.

Early Hominids in Doggerland

Homo sapiens arrived in Europe approximately 45,000 years ago. They coexisted with Neanderthals for thousands of years before the latter finally disappeared.

As water levels rose, Doggerland slowly disappeared. Or sometimes not so slowly – the rate was one to two meters per century, but that gradual inundation could sometimes progress in leaps and bounds. The people who had lived there for countless generations were slowly forced to find higher ground.

A large tidal bay formed in the region around 9000 BC. By about 6500 BC, the British Isles were cut off from the mainland.

More coastlands were wiped out by the Storegga Slide, a submarine landslide off the coast of Norway that caused a tsunami around 6150 BC. The tsunami swept up to twenty-five miles inland in places and probably wiped out twenty percent of the population of the British Isles.

Dogger Bank, what had once been an area of highland hills, remained an island until about 5000 BC. The islands that were the last bits of Doggerland to disappear may have been culturally significant. This enabled groups of people, and possibly even early farmers, to travel across the sea.

By the time Doggerland was swallowed by the sea some eight thousand years ago, agriculture had begun to spread through Europe. In addition to the artifacts hidden beneath the North Sea, there may be buildings to be found down there as well.