Unless you’re an American history buff or student of American Presidential history, you may never have heard the name Edith Bolling Galt Wilson. But for all intents and purposes, she served as the first de facto female President of the United States, from October 1919 to March 1921.

She was the second wife of President Woodrow Wilson who was in office from 1913-1921. Edith Wilson married the widower Wilson in December of 1915, during his first term as president.

But following a severe stroke President Wilson suffered in October of 1919, First Lady Wilson essentially spoke and acted on the president’s behalf. She managed the Office of the President.

This was a role that she later described as a “stewardship.” But most historians now recognize it as having influenced both Domestic and International Policy.

For nearly three years, First Lady Wilson determined which communications and matters of State were important enough to bring to the attention of the bedridden president. And which one were to be delegated to members of his cabinet.

All while keeping Vice President Thomas Riley Marshall unaware of President Wilson’s incapacitation.

Most significantly, perhaps, Edith Wilson worked behind the scenes during the ratification process of the Treaty of Versailles. This was the peace treaty signed on June 28, 1919, that ended hostilities between Germany and most of the Allied Powers.

It was never ratified by the US. Yet, it was crucial to help craft a separate peace treaty with Germany.

Early Life

Edith Bolling (Galt Wilson) was born on October 15, 1872, in Wytheville, Virginia, to circuit-court judge William Holcombe Bolling and Sarah “Sallie” Spears (née White).

Bolling was the seventh of eleven children. She was a direct descendant of the first settlers to arrive at Virginia Colony in the early 17th Century.

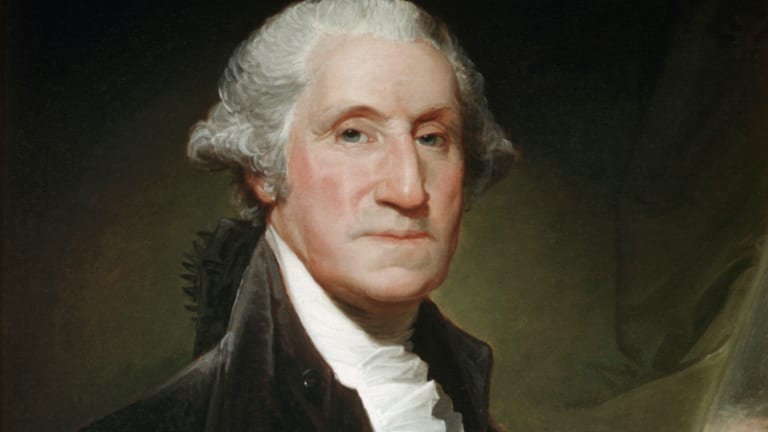

Through her father, she was also a descendant of Mataoka, better known as Pocahontas. She was also related either by blood or through marriage to Thomas Jefferson, Martha Washington, Letitia Tyler (wife of President John Tyler), and the (President Benjamin) Harrison family.

The Bollings were among the oldest members of Virginia’s slave-owning “planter elite” prior to the American Civil War.

Like many of the “planter elite,” the Bollings justified slave ownership by insisting that their slaves were content with their lives as “chattel” and had little desire for freedom. Edith Bolling grew up with these ideas ingrained in her head

After the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished, Edith’s father turned to the practice of law to support his family. Ultimately unable to continue to pay the high taxes on his extensive plantations, William Bolling moved his family to Wytheville, where most of his children were born.

In addition to eight surviving siblings, Edith Bolling’s grandmothers, aunts, and cousins also lived in the Bolling home. This made for constant activity.

Many of the Bolling women had lost husbands in the Civil War. They, as a family, were staunch supporters of the Confederacy.

Education

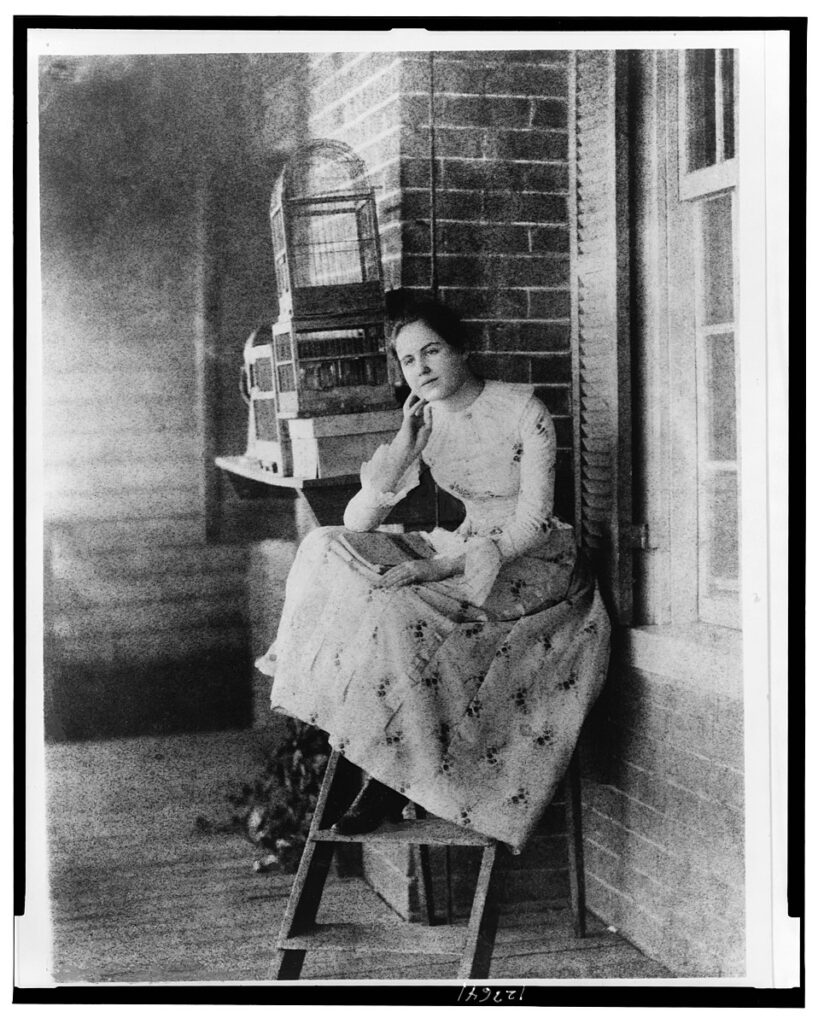

Edith Bolling had little formal education. Her sisters attended various local schools. But Edith was taught at home by her paternal grandmother, Anne Wiggington Bolling, despite being bedridden by a spinal cord injury.

In exchange for learning how to read, write, basic math skills, make dresses, and speak a hybrid version of French and English, Bolling washed her grandmother’s clothes. She also put her to bed each night, and cared for her 26 canaries.

It was her grandmother who instilled a tendency to make quick judgments and hold strong opinions. These were personality traits Edith Bolling Galt Wilson would exhibit her entire life.

When Bolling was 15 years of age, her father enrolled her at Martha Washington College. This merged with the Emory and Henry College in 1918. It was a private finishing school for girls in Abingdon, Virginia; specifically chosen for its excellent music program.

Bolling, however, proved to be an undisciplined, ill-prepared student who constantly complained. She thought that the food was poorly prepared, the rooms were too cold, and the daily curriculum was much too rigorous. It came as no surprise to her family when Bolling asked to come home after just one semester.

Two years later, Bolling’s father enrolled her in Powell’s School for Girls in Richmond, Virginia. This was an environment she apparently liked infinitely better than her former finishing school.

In later years she would write that her time at Powell’s was the happiest time of her life. Unfortunately, the school closed at the end of that year after the headmaster suffered an accident in which he lost his leg.

Concerned about the cost of Edith’s education, William Bolling turned his attention to educating his three sons.

Edith Bolling’s First Marriage

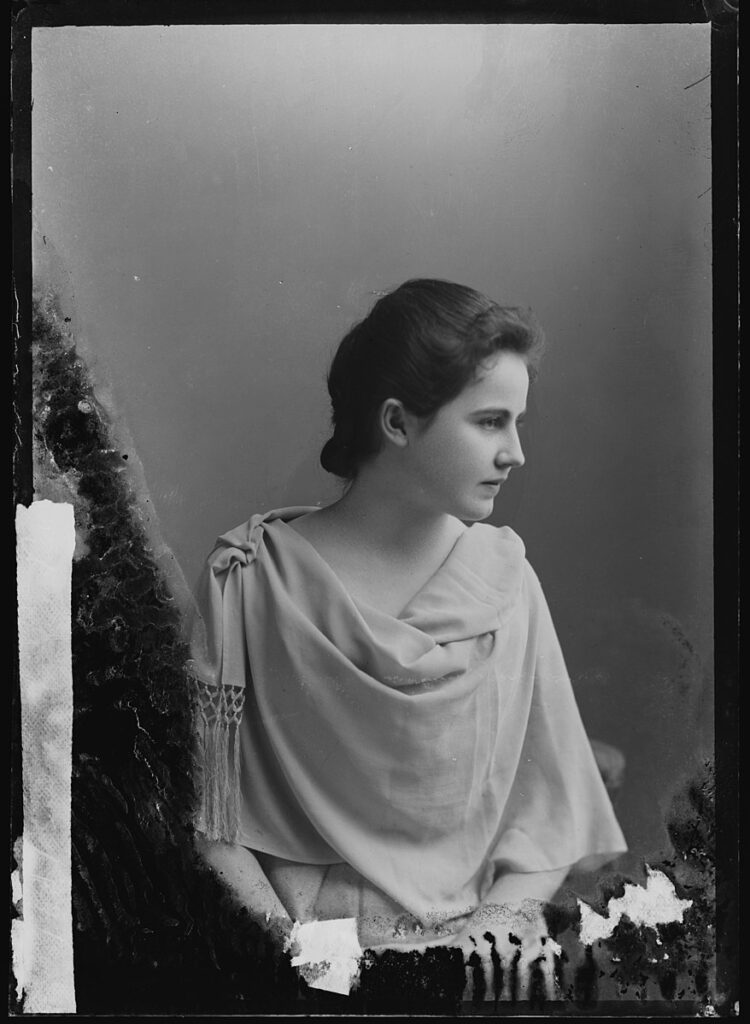

In 1895 while visiting her married sister in Washington, D.C., Edith Bolling met Norman Galt. He was a prominent jeweler associated with Galt & Brothers. The couple married on April 30, 1896, and resided in Washington for the next 12 years.

In 1903, Edith Bolling Galt bore a son to Norman Galt–who lived but a few days. A difficult birth left Edith unable to bear more children.

In January of 1908, Norman Galt died unexpectedly at the age of 43.

Inheriting her husband’s highly lucrative business, Edith Bolling Galt found herself widowed–but quite wealthy.

She hired a financial manager to oversee his business and paid off all his debts. With the money remaining, she began making trips to Europe. There she developed a taste for fine food and haute couture fashion.

But despite her wealth (and what one described as “kittenish” good looks), the widow Bolling Galt was barred from the upper echelons of D.C. high society because her wealth wasn’t old money. It derived from retail rather than shipping, banking, or other more respectable forms of high finance.

(Gaut & Bros. [or just Galt]) exists to this day and is one of the most respected jewelers in the Country.)

Edith Bolling Galt’s Marriage to Woodrow Wilson

In March of 1915, Edith Bolling Galt was introduced to the recently widowed US President Woodrow Wilson at the White House. She was introduced by the president’s first cousin Helen Woodrow Bones.

Bones served as the official White House hostess after the death of Wilson’s wife, Ellen Axson Wilson. (Traditionally, one of the responsibilities of a First Lady was hosting formal affairs at the White House.)

Instantly attracted to Bolling Galt, Wilson proposed soon after their first meeting. However, rumors spread that Wilson had cheated on his wife with Bolling Galt (and had, in fact, plotted the former First Lady’s death with Bolling Galt). This threatened their pursuit of a relationship.

Wilson was concerned about the effect such wild speculation could have on the presidency (and his personal reputation). He advised Bolling Galt to back out of their engagement that they might both save face.

As a compromise, Bolling Galt insisted that they simply keep a low profile and observe the traditional one-year period of mourning.

With no further hindrances, Woodrow Wilson and Edith Bolling Galt married on December 18, 1915, at her home in Washington, D.C. There were 40 guests in attendance.

The ceremony was jointly performed by the groom’s pastor, Reverend Dr. James H. Taylor of Central Presbyterian Church, and the bride’s, Reverend Dr. Herbert Scott Smith of St. Margaret’s Episcopal Church.

Life as the First Lady

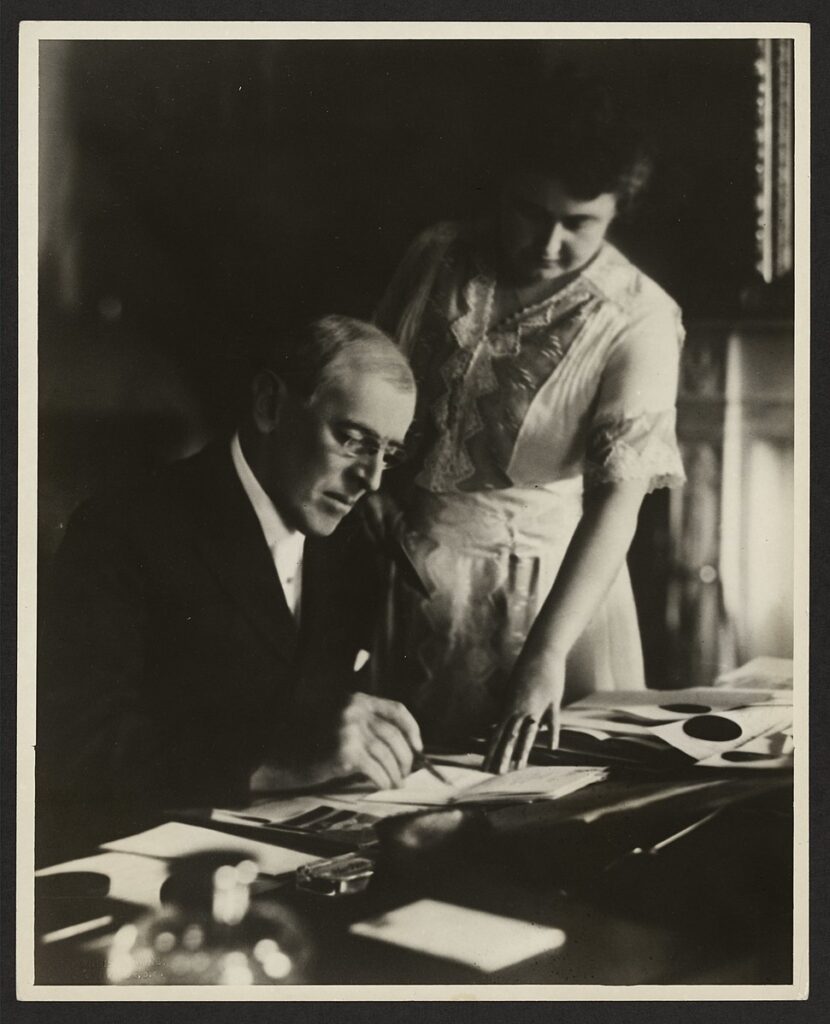

Due to the intense attraction between Woodrow and Edith, the two were seldom apart. Wilson invited her to sit with him when he reviewed important documents.

Some of them were highly secret and related to the war. He even allowed her to be present during critical discussions with his advisers.

But aside from the presidency, Edith’s primary concern was her husband’s health and comfort. She showed little interest in politics except as it related to him.

As First Lady during WWI, Edith Bolling Galt Wilson herself observed all the restrictions imposed on the American people to conserve natural resources during wartime: “gasless Sundays,” “meatless Mondays,” and “wheatless Wednesdays”–in an effort to set an example.

In keeping with these federal policies, she arranged for sheep to graze on the White House lawn rather than use manpower to mow it. She even had their wool auctioned off to benefit the American Red Cross.

Additionally, Edith Wilson became the first First Lady to travel to Europe during her time at the White House. She was qualified for the role of official White House hostess.

However, the social aspect of Wilson’s administration was overshadowed by the war in Europe. She abandoned it completely after the US formally entered the conflict in 1917.

Edith Wilson merged her own life with that of her husband’s, trying to keep him healthy under tremendously stressful conditions. She accompanied him to Europe when the Allies met to discuss terms for peace.

On two occasions, in 1918 and 1919, the First Lady accompanied her husband to Europe to address the troops, and to sign the Treaty of Versailles. Her presence among female royalty of Europe helped secure America’s status as a world power and elevate the status of First Lady in international politics.

She was charming, well-spoken, and highly respected.

Tragedy in the White House

Following his attendance at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 (the international meeting to establish the post-war peace terms), President Woodrow Wilson returned to the US. He was intending to campaign for Senate approval of the proposed treaty.

But quite unexpectedly, the president suffered a massive stroke. It left him bedridden and partially paralyzed. (To this day, his limitations are only speculative.)

It was decided by the president’s inner circle (including his physician and close advisors) that the true extent of the president’s disability be withheld from the American public. Even the vice president. (They wanted no shift in power.)

From October of 1919 to the end of Wilson’s term on March 4, 1921, First Lady Wilson decided which communications and matters of State were important enough to bring to her husband’s attention.

She appointed herself the sole communication link between the president and his staff. She insisted that all memos, correspondence, questions, requests, and pressing matters be directed to her only.

In her biography, My Memoir: Edith Bolling Wilson, Edith Wilson later wrote:

“I studied every paper sent from the different Secretaries or Senators and tried to digest and present in tabloid form the things that, despite my vigilance, had to go to the President. I, myself, never made a single decision regarding the disposition of public affairs. The only decision that was mine was what was important and what was not, and the very important decision of when to present matters to my husband.”

My Memoir: Edith Bolling Wilson

(Historians doubt that this explanation is anything more than her attempt to preserve President Wilson’s legacy.)

After the White House

Upon leaving the White House in March of 1921, Edith and Woodrow Wilson moved into a home on S. Street NW in Washington, D.C. There, she continued to care for the former president until his death on February 3, 1924.

In subsequent years, Edith Bolling Galt Wilson headed the Woman’s National Democratic Club’s board of governors when the club formally started in 1924. She subsequently published her memoir in 1939.

A permanent fixture in American politics, Edith Wilson was present during President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s address to Congress on December 8, 1941. This was the day after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor.

This speech was when he asked Congress to declare war. This intentionally drew a link to President Wilson’s April 1917 Declaration of War against Germany.

Four years later, on April 14, 1945, the former First Lady Wilson attended Roosevelt‘s funeral at the White House. She was also present on January 20, 1961, for the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy.

On December 28, 1961, at the age of 89, Edith Bolling Galt Wilson died of congestive heart failure just days before what would have been her husband’s 105th birthday.

She is buried next to her husband at the Washington National Cathedral.

Ongoing Controversy

Until her final days, former First Lady Edith Bolling Galt Wilson insisted that she never exercised the full power of the presidency. At best, she used some of its prerogatives on behalf of her husband.

But in more recent years, scholars have become increasingly more critical of Edith Wilson’s tenure as First Lady. They are now able to consider the long-term effects of her term as De Facto President.

Historian Phyllis Lee Levin has stated that the effectiveness of Woodrow Wilson’s policies was unnecessarily hampered by his wife. She called her “a woman of narrow views and formidable determination.”

Other critics have declared that Edith Bolling Galt Wilson naively underestimated her own role in her husband’s presidency. While she may not have made “critical” decisions, she influenced domestic and international policy.

She played a part in deciding which matters to bring to her husband’s attention. She prioritized these matters according to her own values and understanding of politics.

Similarly, medical historian Dr. Howard Markel has taken issue with First Lady Wilson’s claim of a “benign stewardship” in his article called, “When a Secret President Ran the Country.” He stated emphatically that Edith Wilson “was, essentially, the nation’s chief executive until her husband’s second term concluded in March of 1921.”

Even a century later, historians hesitate to underestimate Edith Bolling Galt Wilson’s true political legacy—or that of her husband.

References

britannica.com., “Edith Wilson,” Edith Wilson | American First Lady, WWI Activist & Widow of Woodrow Wilson | Britannica

pbs.org., “When a secret president ran the country,” When a secret president ran the country | PBS NewsHour

biography.com., “Edith Wilson: The First Lady Who Became an Acting President — Without Being Elected,” Edith Wilson: The First Lady Who Became an Acting President — Without Being Elected (biography.com)

npr.org., “A new biography of first lady Edith Wilson examines her political influence,” https://www.npr.org/2023/03/15/1163669149/a-new-biography-of-first-lady-edith-wilson-examines-her-political-influence

firstladies.c-span.org., “Edith Wilson,” https://firstladies.c-span.org/FirstLady/30/Edith-Wilson.aspx

archive.org., My Memoir, https://archive.org/details/mymemoir0000wils_d6c9/page/n3/mode/2up

historynewsnetwork.org., Phyllis Lee Levin’s Edith and Woodrow, https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/519