Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, has long been heralded as the cradle of civilization. Around 6000 BC, once-nomadic peoples began settling down, farming, and domesticating animals, giving rise to settlements that eventually grew into towns, cities, and even empires.

Many great civilizations would call this region home and leave behind enormous legacies – southern Mesopotamia was inhabited by the Sumerians, the central region was home to the Akkadians and Babylonians, and the Assyrians arose in the north.

However, arguably the most significant legacy of Mesopotamia was no single empire – but instead, its profound impact on the development of education, learning, and scholarship, helping to shape human history as we know it today.

The invention of Writing and Need for Scribes

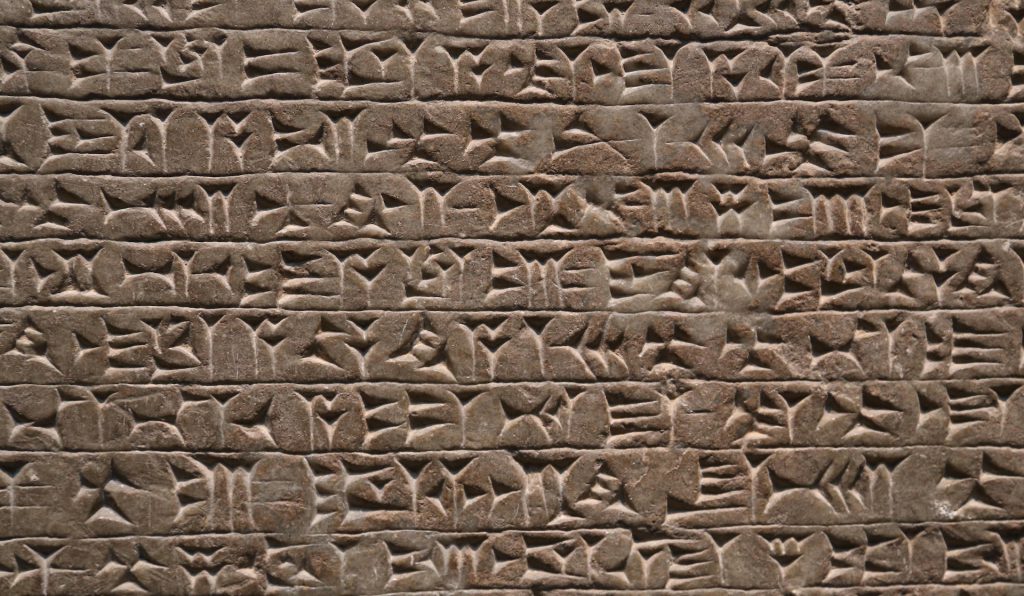

As far as we know, the earliest invention of written language occurred here in Mesopotamia, specifically in Sumer, around 3400 BC. While the writing began as simple pictographs on clay tablets, it quickly evolved into the language we today refer to as cuneiform.

Although these scratches and wedge-shaped marks must have begun as little more than accounting tools, they developed to enable the writing down and recording of all things imaginable.

With the invention of the cuneiform writing system, the Sumerians – and subsequent Mesopotamian civilizations – began to record everything they could, from business records, inventories, and palace orders, to religious hymns, poems, and stories.

Kings and priests realized the value and necessity of educating scribes – literate individuals who could read and write, who ranged from copyists to librarians to teachers.

As a consequence, Mesopotamia developed a formal education system. Notable for both its diversity and rigor, it was largely practical training and aimed to mold scribes and priests, but altogether, it represented something much larger.

Little did they know then that it would symbolize the burgeoning of a cornerstone of intellectual pursuit and education for the world.

Mesopotamian Schools and their Exclusivity

Throughout Mesopotamia, temples established formal schools to educate young boys as scribes and priests. Initially, these scribal schools were solely linked to temples, but gradually, as the institution expanded and grew its foothold across society, secular schools took over.

Established scribes started their own schools to teach writing and reading, charging high fees for tuition. But, unfortunately, this simply created a situation where only families who were affluent, rich, and powerful could afford to enroll their children in these schools.

In this arrangement, young boys would usually start around seven or eight years old and would join government officials, priests, and wealthy merchants in attending school just about every day.

Education, for the vast majority, was available to only boys throughout ancient Mesopotamia, a shameful facet of society that has only been widely challenged in recent history.

Sometimes, albeit very uncommon, girls would learn to read and write and attend school, although only if they were king’s daughters or training as priestesses.

The teachers were strict disciplinarians, mostly former scribes or priests, who punished children for any misbehavior. Education was designed to be practical, aimed at training scribes and priests, and included basic reading, writing, and religion, but advanced to higher learning in law, medicine, and astrology.

The libraries in the temples were the centers of intellectual activity and training, supervised by influential priests. The priestly education was thorough and dominant across Mesopotamian culture and would grow to exert a strong influence on the ruling class and authorities of the time.

Formal Education Methods and Topics

Ancient Mesopotamian education was largely focused on literacy – the ability to read and write – with cuneiform writing a particularly challenging skill for students to master.

Scribes were often trained for around 12 years. However, few Sumerians were literate due to the complexity of cuneiform; literacy across Mesopotamia would remain low for millennia, not just in ancient Sumer.

As noted previously, teachers could be harsh disciplinarians in their instruction. Instead, they punished mistakes and disobedience with whippings, leading to an expectation of obedience and hard work from their students.

Students learned many subjects besides reading and writing, like math, history, and many others. These included geography, zoology, botany, astronomy, engineering, medicine, and architecture.

While schooling was only available to the elite and wealthy, students still had to work quite hard to learn the skills of a scribe. Constant practice, oral repetition, reading various texts, and copying models were the main teaching and learning methods.

The exact copying of scripts was the most strenuous and served as the test of excellence in learning. Altogether, the Mesopotamian education period was a long and rigorous journey for students, and discipline was often harsh.

Ultimately, graduates could become priests with more training or work as scribes for the military, palace, temple, or businesses.

Graduating the Education System

After receiving an education in ancient Mesopotamia, students could expect to pursue various professions and roles crucial to the functioning of society.

One obvious but prominent career path was that of a scribe, like many of their teachers. This involved recording and managing written records for businesses, temples, and the government.

Scribes were crucial for all needs related to the workings of government and the economy. Keeping accurate records of transactions and laws was essential for maintaining economic and political stability.

Many students also continued on in their studies to join the priesthood. Throughout ancient Mesopotamian history, the priestly class dominated and, almost essentially, ruled over the society.

Next to kings in the power structure of Mesopotamia, priests oversaw just about every facet of societal life – construction, worship, economic matters, and even conflict or war.

Graduating from scribal school to join the priesthood meant a life of great power and wealth for many.

Other common professions in Mesopotamia, such as bureaucrats, also owed their positions to their education, as many were required to be literate to a degree.

Women also had opportunities in Mesopotamian society after their education. For those lucky enough to gain an education, many became priestesses.

The Legacy of Mesopotamian Education

These professions and roles played a key role in the development of Mesopotamian society. As a result, education and professional training were highly valued in Mesopotamia, and those who were educated and skilled in various professions held significant positions of influence and respect.

Their work and contributions – made possible by the education system – helped shape the development of Mesopotamian civilization, and their roles were essential for its growth and success.

Sources

“Bringing Education in Ancient Mesopotamia to Life.” CORDIS, European Commission, 3 June 2022, https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/436441-bringing-education-in-ancient-mesopotamia-to-life.

“Education in the Earliest Civilizations.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/education/Education-in-the-earliest-civilizations.

Mark, Joshua J. “Mesopotamia.” World History Encyclopedia, 14 Mar. 2018, https://www.worldhistory.org/Mesopotamia/.

“Visit Resource: Mesopotamia.” The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/learn/schools/ages-7-11/middle-east-and-asia/visit-resource-mesopotamia.