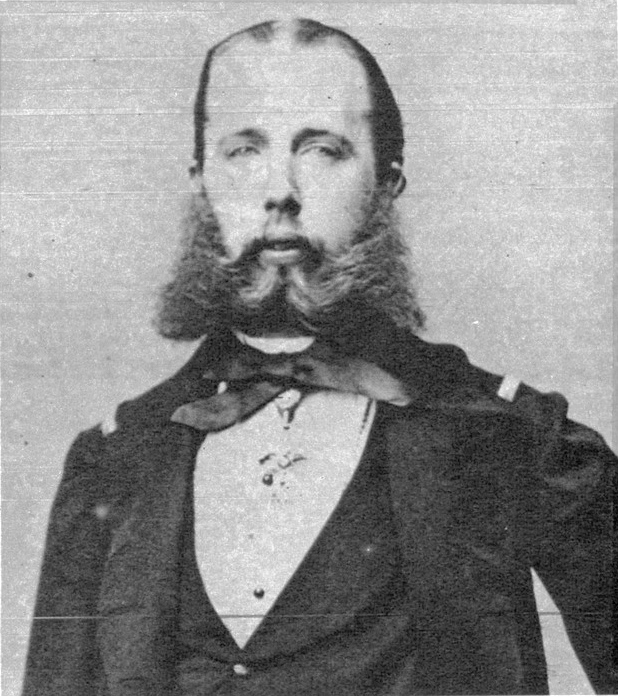

In 1863, the young archduke Maximilian was approached with an intriguing offer from Emperor Napoleon III of France. He wanted to know if Maximilian had any interest in becoming the emperor of Mexico, a country that he had never set foot in.

At this time, Maximilian was 30 years old. He had been a naval leader and the governor-general of a portion of the Austrian Empire, which his older brother ruled. But Maximilian wasn’t sure if he wanted more power.

Ever since war had broken out between Austria and Italy in 1859, Maximilian had retired to his castle in Trieste. There, he dedicated himself to two of his passions – art and literature.

The offer to rule a distant and politically unstable country did not at first pique his interest. But after subsequent talks with Napoleon, his brother Franz Josef of Austria, and King Leopold of Belgium, Maximilian finally agreed.

In 1864, he sailed into the port of Veracruz and accepted the Mexican crown. Little did he know, his imperial project would end just three years later and he would face the harsh reality of a Mexican firing squad. This is the strange story of Emperor Maximilian, the second and last emperor of Mexico.

Prelude to Invasion

In the years before Maximilian landed in Mexico, the country was caught in a political tussle between conservatives and liberals. The conservatives were proponents of a strong Catholic Church and maintaining the kind of society that was in place under the Spanish.

The liberals wanted to reduce the power of the church, allow freedom of religion, and expand suffrage for male citizens. They wanted to achieve Jeffersonian’s ideal democracy, a democracy composed of a large class of small landowners.

These two competing groups alternated in power, each trying to impose their vision of Mexico on the country. When the liberals were in power, they took away the clergy’s special privileges and sold off a large percentage of church lands.

The conservatives were extremely wary of these perceived attacks on their political agenda. When the conservatives returned to power in 1857, they rolled back many of the earlier changes made by the liberals.

Between these two polarized groups, the liberal party itself was split into the moderates (moderados). They shared some conservative values. And the purists (puros) who sought more radical changes. Such as a more equal distribution of land and political power.

The end result of these opposing political projects was a clash that led to civil war. The two leaders to emerge at the head of these two groups were Benito Juarez for the liberals and General Félix Zuloaga for the conservatives. The civil war, known as the War of Reform, lasted from 1857 to 1860 when the liberals finally reoccupied Mexico City on December 25, 1860.

The Conspiracy to Conquer Mexico

Once the liberals returned to power, they held elections for a new president. But that didn’t end the hostilities. There continued to be violence in the countryside, with peasant uprisings periodically destabilizing the country.

In this climate of violence and political instability, Mexico decided it could no longer pay its public debt. You see, Mexico’s previous governments had been borrowing heavily from Spain, France, and England to pay for its infrastructure and armies.

Once Mexico reneged on those debts, the three European powers that had been funneling money into the country came together to decide what to do about Mexico’s refusal to pay.

Their solution? To send warships to Mexico to seize the customs houses but not take any further action that would impede Mexico’s sovereignty.

The customs houses were important because that was where a country collected duties on imported goods. By seizing control of Mexico’s customs houses, the European creditors would be in control of a large part of Mexico’s income. They could therefore ensure that all of their debts were paid back.

For Spain and England, this was enough. But France had other plans.

Maximilian Becomes Emperor

What became known as the Tripartite Powers – England, France, and Spain – reached Mexico’s eastern coast in the spring of 1862. Benito Juarez and his government promptly promised the three powers that they would repay all of their debts as soon as they possessed sufficient funds.

Spain and England were satisfied with the promise, but not France. After the Spanish and English ships sailed away, the French made their way to Mexico City.

This first French attempt at invasion was stopped in its tracks on May 5, 1862, by a combined army of indigenous and mestizo defenders. This date is now celebrated all over the world as Cinco de Mayo.

The Mexican victory on May 5th was important because it meant that the French were forced to wait a year before they could try again with reinforcements. But once reinforcements arrived in January 1863, the French quickly captured Mexico City and installed Archduke Maximilian as emperor of Mexico.

This was the beginning of the short-lived “Second Empire of Mexico.” Maximilian had no idea what he was getting himself into.

He did his best to promote European liberalism but ended up alienating both the conservatives and the liberals. He decided not to return church lands that had been sold off and he allowed freedom of worship. Both of which made him an enemy of many conservatives.

He also abolished corporal punishment, reduced the maximum number of work hours, and even implemented a minimum wage for farm workers.

Despite Maximilian’s best efforts, he was still seen as the enemy by both the liberals and the conservatives. Benito Juarez fled Mexico City before the French arrived and waged a three-year guerrilla war against him.

At first, the former Mexican president lacked men and supplies. By 1865, Maximilian’s troops pushed him to the southern border of the United States. But thanks to that northern neighbor, Benito Juarez would see his fortunes change.

The Role of the U.S. Civil War

Decades before the French invasion of Mexico, the United States had laid out a policy of European non-intervention in the Western hemisphere.

In 1823, President Monroe made it clear in what became known as the Monroe Doctrine that the United States would not tolerate any interference by European powers in the politics of sovereign Latin American countries.

The French invasion, then, was a clear violation of the Monroe Doctrine.

But in the early 1860s, the United States was caught up in a civil war. President Lincoln lacked resources. He worried that if he confronted the French about their meddling in Latin America, they might end up coming to the aid of the Confederates.

Thus, during the three years that the French were pushing Benito Juarez farther and farther north, the United States could do nothing more than simply sit by and watch as France extended its control over Mexico. Neither the United States nor any of the Latin American countries save for Brazil, had recognized France’s Mexican empire.

But in 1865 the Civil War ended with a Union victory. Maximilian tried to secure a diplomatic relationship with incoming President Andrew Johnson, but those diplomatic missions failed.

Not long after, the United States started sending weapons, money, and even troops to aid Benito Jaurez’s cause. With the power of the United States at his disposal, Benito Juarez finally stood a real chance.

Maximilian’s Downfall

Even with the support of the United States, Benito Juarez was still in trouble. General Auguste Henri Brincourt led a French force of 2,500 northward and captured Benito Juarez’s makeshift capital at Chihuahua City.

That forced Benito Juarez to flee to what is now Ciudad Juarez, across the Rio Grande from El Paso, Texas. Meanwhile, Brincourt declared victory and even called his action, “the last military act” of the invasion.

He would soon eat those words.

You see, the French invasion of Mexico was highly unpopular back in France. It was expensive too, and Napoleon needed to ensure he had enough strength to address the rising threat of Prussia to his east.

Thus, in 1866, Napoleon decided to withdraw French troops from Mexico. Maximilian’s wife, Carlota, who had pushed him into taking the throne in the first place, sailed to Europe and tried to convince Napoleon to provide support for Maximilian’s empire.

Her efforts failed, however, and she ended up having a nervous breakdown. She never returned to Mexico.

Without the support of the French army, Maximilian’s control over the north of Mexico quickly withered away. He had never really had the support of the countryside, anyway.

Lacking an army to enforce his will, the forces of Benito Juarez began pushing southward, finally reaching the last holdout at Querétaro. Maximilian personally led the 9,000-man defense of the city but after a months-long siege, the city finally fell and Maximilian was captured.

Unfortunately for Maximilian, he had signed an order near the end of the conflict that gave his forces the authority to execute any rebel found to have bore arms against the empire. Known as the “black flag” decree, it essentially sealed Maximilian’s fate.

Although Benito Juarez faced strong international pressure to pardon the one-time emperor, he tried him as a rebel, and, found guilty, sentenced him to be shot by firing squad.

On June 19, 1867, Maximilian was lined up with two of his top generals. Before being fired upon, Maximilian shouted in Spanish, “I forgive everybody, I pray that everyone may also forgive me, and I wish that my blood, which is now to be shed, may be for the good of the country. Long live Mexico, long live independence.” Then the soldiers fired and Mexico’s emperor crumpled to the ground.

A Series of Lies and Mistakes in Hindsight

At first glance, France’s attempt at setting up an empire in the Western hemisphere seems ludicrous. To plant a man who had never set foot on Mexican soil before taking over as ruler and expecting him to succeed is nothing short of foolish.

But when you delve into the history of how events unfolded, there was a period in which it wasn’t so unthinkable to imagine Maximilian’s Second Mexican Empire from taking shape. After all, Maximilian had both a strong French army at his disposal and a large portion of Mexican conservatives on his side.

Unfortunately, for the young archduke, his adventure in Mexico quickly got away from him. He alienated both the liberals and the conservatives with his well-intentioned, yet politically tone-deaf policies.

He never managed to build any kind of real base of support. He was ultimately forced to rely on his French troops to maintain order. For a while, that was enough.

He fought Benito Juarez and his supporters as far north as the US-Mexico border and nearly dealt Juarez a final blow. But things changed when the United States freed itself from its own civil war and cast its eye southward.

Once United States military aid started pouring in, Benito Juarez’s ragged army became reinvigorated. As it took on renewed strength, it pushed Meximilien’s forces back toward the capital.

Then Napoleon withdrew his troops. As the last of the French soldiers sailed out of Mexico, one can only imagine the sinking feeling that Maximilian must have experienced. He held out for as long as he could but finally fell into rebel hands. When he was executed by firing squad on June 19th, 1867, he was only 34 years old.

While it may be difficult to sympathize with an aristocratic outsider with imperial ambitions, the role of Maximilian in this strange episode of Mexican history does have a tragic element to it. As foolish as his undertaking may have been, he was in some ways a pawn of the conservative elite and Napoleon himself.

When Maximilian agreed to become emperor of Mexico, he did so under two conditions – that it would be the will of the Mexican people that he be their emperor and that he would have protection from the French army.

Napoleon provided him with troops but ultimately withdrew them when Maximilian needed them most. And while he was told that the Mexican people had voted in favor of his arrival, that turned out to be a lie fabricated by Mexican conservatives.

However you choose to look at Maximilian, he seems to have done everything he could for the Mexican nation. In the end, that wasn’t enough to change the disastrous outcome.