It all started with shoes.

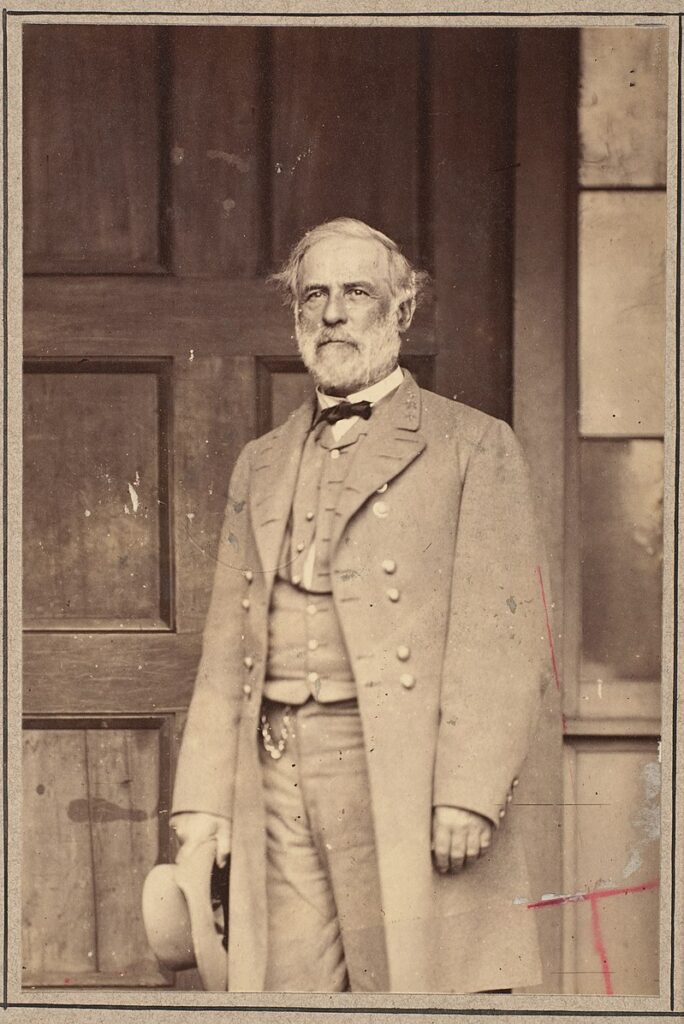

The reason Robert E. Lee sent General Harry Heth to Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, was to forage for footwear, which was rumored to be there. This search was emblematic of the South’s predicament in the US Civil War.

It could not hope to win militarily in an attritional war against the much more industrialized Union. The North had significantly more resources in population and industry to draw upon. The South had to forage for shoes.

Its only hope was not to lose and for the North to give up the fight. This was what Lee set out to do in the campaign that led him to Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863.

Lee’s String of Casualties

Earlier, Lee was losing, even though he won at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May.

He won a battle but lost the critical lieutenant that planned it for him. Without Chancellorsville, there wouldn’t have been any invasion of the North. Losing General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson likely meant there would be no victory in the subsequent campaign.

Lee’s army, executing Jackson’s plan, outflanked, and defeated northern General Joseph Hooker decisively at Chancellorsville. This victory opened the door to the northern campaign.

A northern campaign was essential if the South had any chance of winning. The Confederacy could not win an attritional war fighting on its territory. Foreshadowing the future the South faced, Lee was advancing into Maryland and Pennsylvania, and the Mississippi campaign of General U.S. Grant was threatening to cut the Confederacy in two.

The Siege of Vicksburg would end the day Lee withdrew from Gettysburg. Grant’s victory there cut the Confederacy in half.

The Confederacy’s only hope was to get the North to sue for peace. A series of victories in the Union heartland might convince European powers such as France and Britain, both dependent on Southern cotton, to pressure the Union to come to terms or face military intervention from outside.

However, the biggest hope was to get northern citizens to reject the continuance of the ongoing bloodshed. There was some reason to hope this might happen. A week after the Union victory at Gettysburg, draft riots broke out in New York City.

Defensive Strategies Leading Up to the Battle

Military technology at this point was already favoring defensive stances. Direct attacks on defended positions required the application of overwhelming force.

By July 1863 Grant was already besieging Vicksburg, the last Confederate fortress on the Mississippi for months by this time. In all the clashes so far, the side that attacked suffered the worst casualties.

The range of Civil War weaponry coupled with even rudimentary field fortifications would overwhelm even the most resolute attackers, or at least cause massive casualties. (Hagerman)

General Jackson, an astute student of military history, recognized this. His strategies involved misdirection and getting the enemy to attack prepared positions whenever a battle was unavoidable.

In the valley campaign of 1862, Jackson tied up forces in the Shenandoah Valley with a force that was a third of the size of the Union forces arrayed against him. He did this through feints and misdirection before forcing the Union generals to attack his positions.

His actions kept these forces from reinforcing General McClellan’s attacking army at the gates of the Southern capital, Richmond.

Jackson was also the mastermind of the victory at Chancellorsville. Instead of attacking the main Union force, he discovered a way around the flanks. This indirect attack allowed Lee’s Army to defeat a much larger army under Hooker.

However, Chancellorsville was to be Jackson’s last battle. As he led a party surveying the army’s positions, one of his own pickets shot him. He lay dying even as the Confederates celebrated his brilliant victory.

That soldier’s shot probably cost the Confederacy the war. Lee was a masterful, defensive tactician.

However, when felt he had to attack, he all too often mimicked his northern colleagues and engaged in battles of assault rather than maneuver.

Lee, however, conducted the initial phases of the Gettysburg campaign in a manner that Jackson would have approved of.

The Armies Start Establishing Their Positions

Lee’s army avoided the concentrations of Union forces around Washington, DC, and instead pivoted toward the Pennsylvanian capital, Harrisburg. His forces met little opposition and induced panic on the Union side.

From his position in southern Pennsylvania, Lee could strike out against either Baltimore, the largest city in the slave state of Maryland, and a crucial port and rail link only 30 miles from the capitol in Washington, DC.

Or, even more spectacularly, he could have marched on to Philadelphia and severed the main rail artery that connected the Union as well as symbolically capture the first American capital.

General Meade, who replaced Hooker after the disaster at Chancellorsville, recognized the peril that the Union faced. He had to pick one route Lee might take and leave the other one undefended.

Meade, ever cautious, positioned his army along the routes to Washington, DC, and Baltimore, leaving the road to Philadelphia wide open.

Lee thus struck into virtually undefended space. Now well north of the Union army, he could move in any direction while his Federal opponent, newly appointed (June 28) Army of the Potomac commander George G. Meade, could do little more than react to Lee’s initiatives.

(Alexander, p. 111)

Lee’s Critical Misjudgment

At this critical juncture, Lee lost his strategic awareness.

General Jeb Stuart’s cavalry engaged in a wide-ranging raid/reconnaissance to the north and west and lost contact with the main army. The Confederate commander did not know whether significant Union forces blocked the road to Baltimore or the one to Philadelphia.

This uncertainty should not have forced Lee’s hand into attacking Gettysburg. While it was an important road junction, it was not strategically essential to him.

Instead, he could have fortified one of the many strong defensive positions in the area and waited for the Union army to dislodge him. This would have turned the tables on the subsequent battle.

Meade had to move because he was trying to defend multiple fronts and was caught on the back foot by the defeat of Chancellorsville. If Lee was in Pennsylvania, the Union cause was in danger. Meade could not sit idle and wait to see what he would do.

Once he was deep into Union territory, however, Lee was not faced with the same imperative. Jackson would have recognized this. Lee did not.

Instead, the great Southern general allowed a meeting engagement between General Heth’s division and Union cavalry to escalate into the decisive battle of the Civil War.

Instead of Lee adopting the defensive position, and forcing Meade to attack him, he insisted on attacking an increasingly well-prepared and growing Union force over the next two days.

While there were opportunities throughout the battle to save it for the Confederacy, the decision to attack in the first place probably doomed the Southern chances of ending the war in their favor in the summer of 1863.

July 1: The First Day of Battle

The morning of July 1st involved a meeting engagement between Confederate General Heth’s division and the Union cavalry under General John Buford.

Thinking that the Union troops in town were nothing more than local militia, and seeking the supplies supposedly stored there, General Heth ordered two of his brigades to push into the town. What they didn’t realize was that Buford’s cavalry was the vanguard of the Union Army of the Potomac, moving up from the south.

The first units to reinforce Buford were elements of General John F. Reynolds I Corps. They stiffened the Union resistance just north of town, although General Reynolds died in the action.

In the early afternoon, the XI Corps, under General Oliver Howard, arrived to establish a crescent-shaped salient north of Gettysburg. However, Confederate General Richard Ewell’s corps arrived from the northeast, collapsing the position and forcing the Union soldiers to retreat through the town.

To the south, Union troops also seized Seminary Ridge, which ran parallel to Cemetery Ridge to the west. The main body of Lee’s Army, however, attacked those positions late in the day, seizing the high ground about a mile across a valley.

The forces retreating from Gettysburg took up positions along the crest of Cemetery Ridge. This ran in a southerly direction starting just south of the settlement and about a mile to the east of the Confederate positions on Seminary Ridge.

General Ewell did not press his attack as these troops established their position that evening. Overnight, troops from both sides reinforced their positions.

SOURCE: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gettysburg_Battle_Map_Day1.png

July 2: The Second Day of Battle

General Meade wanted to establish a line straight down Cemetery Ridge.

General George Sickles, commanding the III Corps of the Union Army of the Potomac, determined that his position on the ridge was vulnerable because he did not also control a rise to the front of it.

He, therefore, pushed his corps forward of where Meade intended it to be and occupied two positions that would become infamous in the coming battle: The Peach Orchard and Devil’s Den. Both features occupied the southern flank of the Union line but jutted out into the valley between Cemetery and Seminary Ridges.

Unbeknownst to Sickles (or Meade), this area was where Lee elected to attack on July 2 as he attempted to turn the southern flank of the Union position.

The Peach Orchard, a stand of trees roughly midway between the opposing ridges, and the Devil’s Den, a boulder-strewn area at the foot of the hill known as Little Round Top, became scenes of fierce fighting that drew in forces and destroyed them.

View of Devil’s Den from Little Round Top

(photo by Tom Haymes)

SOURCE: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gettysburg_Battle_Map_Day2.png

General James Longstreet, Lee’s second and commander of the Confederate First Corps, oversaw this part of the attack.

He aimed to take the two hills that overlooked the Union position from the south so that he could emplace artillery and enfilade Meade’s forces.

Over the course of the day, he continuously fed forces, first through the meat grinder of Sickles’s exposed position, and then up the hill, where his troops met the famous 20th Maine under Colonel Joshua Chamberlain.

View of Big Round Top from Col. Chamberlain’s position on Little Round Top

(photo by Tom Haymes)

SOURCE: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gettysburg_Battle_Map_Day2.png

Sickles’s Corps was decimated over the course of the day.

Chamberlain’s 700 troops held off repeated assaults up the hill as Confederate units filtered around the southern flank and charged the hill. Out of ammunition, Chamberlain ordered his troops to fix bayonets and charge, breaking up the last Confederate charge of the day.

Inexplicably, the Confederates never attempted to put artillery onto Big Round Top, which would have dominated both Chamberlain’s position and the southern end of the battlefield.

On the northern flank, Ewell’s Corps repeatedly assaulted Culp’s Hill to break into the Union rear from there. This feature was critical because it dominated the Baltimore Pike and Union supply areas.

Ewell’s attack did not get underway until late in the afternoon, giving General Hancock time to rush reinforcements to the sparsely defended position.

While the Confederates achieved partial success and seized some of the Union lines, they did so at a severe cost in terms of casualties. Counterattacks drove them out of even those limited gains early the next morning.

July 3: The Final Day of the Battle

On the final day of the battle, Lee, having failed to flank Meade to either the north or the south of his line, decided that he must be weak in the middle.

Lee had three divisions that had either just arrived or were still fresh. He concentrated these forces along the center of the line, along with most of his artillery.

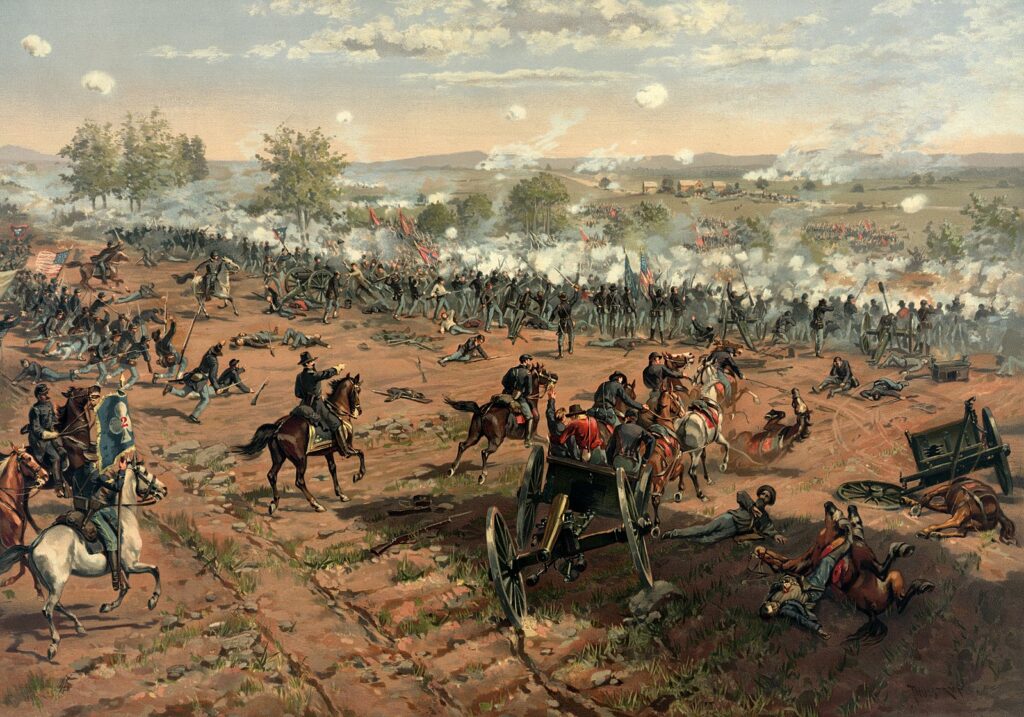

Pickett’s Charge on July 3. The Confederates advanced from right to left in this photo.

(Photo by Tom Haymes)

SOURCE: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pickett%27s-Charge.png

Opening with a blistering artillery barrage, 12,000 Confederate soldiers from 3 divisions (only one of which was commanded by General George Pickett) advanced across open terrain toward General Hancock’s II. Corps at the center of Meade’s line.

Meade, however, had expected this move and placed most of his artillery along this stretch of the line. After engaging in counter-battery fire with the Confederate cannon, these guns reloaded with grapeshot and tore enormous holes in the advancing infantry.

The Union soldiers opened up a disciplined series of volleys. One last lunge from the Confederates breached the line, but then the survivors broke and fled in the face of the withering fire.

The three Confederate divisions taking part in “Pickett’s Charge” suffered over 50% casualties in their suicidal charge. This dwarfed that of the ill-fated British Light Brigade less than a decade before.

Pickett’s Charge was Lee’s last gamble of the battle. It failed. The Union line held.

Other than some cavalry skirmishes (Jeb Stuart had finally turned up) along the fringes of the battle area, the Battle of Gettysburg was over. Lee had his force dig in for a day, hoping Meade would attack his prepared position, but then, on July 5th, he ordered a withdrawal back to Virginia.

Meade, his forces exhausted, failed to trap Lee along the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia escaped into the Shenandoah Valley.

The Aftermath

The Battle of Gettysburg remains the bloodiest battle ever fought on American soil.

Over the course of 3 days, 50,000 of the 150,000 troops on both sides became casualties. Lee lost 30% of his army and, unlike Meade, who lost 25%, those were men the underpopulated South could not replace.

Gettysburg would be the last time the South would threaten the North with an invasion.

Instead, General Grant, brought back from the West by President Lincoln, would grind down Lee over the next 21 months in attritional battles whose outcome was inevitable.

In April 1865, Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox Courthouse, near Lynchburg, Virginia.

References

Alexander, Bevin. Sun Tzu at Gettysburg: Ancient Military Wisdom in the Modern World. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2012) Kindle Edition.

Hagerman, Edward, The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1988).

Keegan, John, The American Civil War: A Military History (New York: Knopf, 2009)