It’s immediately clear from even a brief reading of history that humans have long had a knack for devising methods of torture and execution.

Imagine a world where the fate of criminals extended far beyond the gallows. Where the condemned found themselves trapped in a metal cage, hanging in chains for all to see. This grotesque spectacle, meant to deter and horrify, is known as gibbeting.

An ancient form of public execution and punishment, gibbeting is one such method that casts its own haunting shadow throughout history. And its history is a grim expedition into the world of crime, justice, and ultimate punishment.

Origins of Gibbeting and Early Practices

Gibbeting is derived from the French word “gibet,” which means “gallows.” It was a gruesome practice used as a deterrent back in ancient times and also in recent centuries.

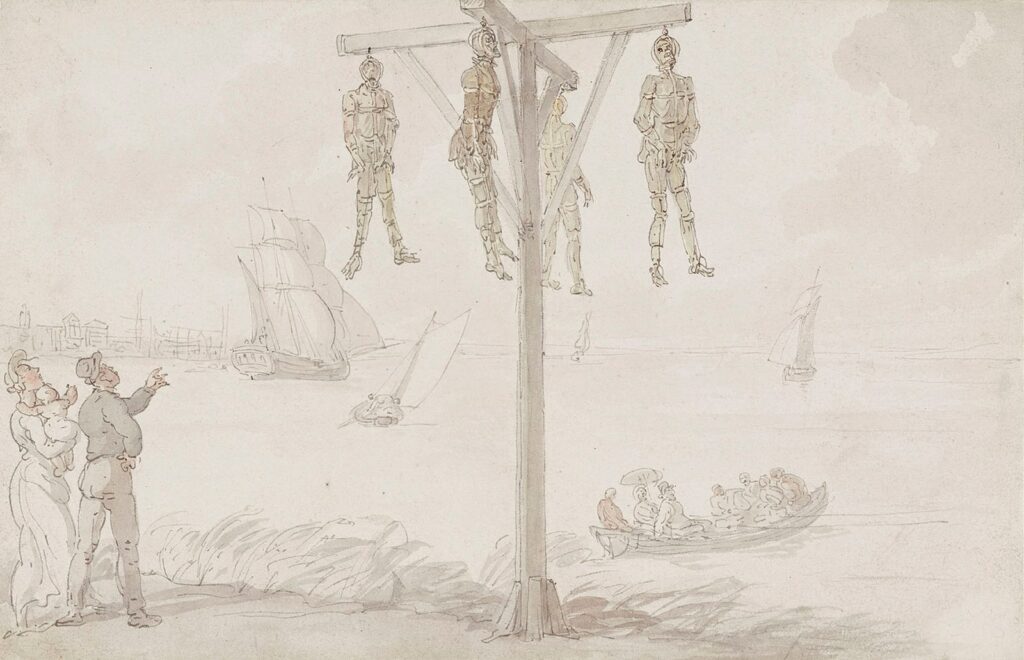

Although not an official part of the legal sentence, it involved hanging the dead bodies of executed criminals in chains known as gibbet cages as a visible warning to potential wrongdoers. These gibbets consisted of upright posts with projecting arms. They were a gallows-type structure and were strategically erected in prominent locations such as hilltops or busy roads to ensure widespread visibility.

The dead or dying bodies were coated with pitch or tallow to delay decomposition. They would then linger in chains, serving as a harrowing reminder of the consequences of criminal acts.

The origins of gibbeting trace back to antiquity, with instances of similar practices seen in the Old Testament and public crucifixions from historical accounts. Notably, in AD 60-61, Boudica’s army reportedly employed gibbeting during the massacre of Roman settlers in Camulodunum, Londinium, and Verulamium.

Over time, the term “to gibbet” came to signify any act of holding up someone to public infamy or contempt. Though abolished in modern times, the eerie legacy of gibbeting serves as a stark reminder of the brutality of past justice systems and the enduring human fascination with macabre displays of punishment.

Gibbeting in England: The Era of the Bloody Code

Nobody was more invested in the brutal practice than England, however. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, England, along with Wales and Ireland, witnessed a grim period known to modern historians as the “Bloody Code.”

This set of laws mandated the death penalty for an extensive range of offenses. This led to a staggering increase in capital punishment cases, even for what would be considered minor crimes by modern standards.

Within this era, gibbeting emerged as a common law punishment, often imposed alongside execution. The Murder Act of 1751, part of the “Bloody Code,” formalized this practice. It allowed judges to sentence convicted murderers to be gibbeted.

The structures had an ominous iron gibbet cage that was intended as a deterrent. They were a visible warning to potential wrongdoers. A gibbet erected close by, featuring particularly notorious criminals’ bodies in a human-sized bird cage of a structure, would make one think twice.

Although the intention behind gibbeting was deterrence, the public response was complex. Some individuals expressed disgust, and there were objections on religious grounds, arguing that prosecution should not extend beyond the criminal’s death.

The sight and smell of decaying corpses hanging in gibbets were also not only offensive but eventually considered a threat to public health. Furthermore, it was not uncommon for pirates to also be gibbeted. Executed near tidal sections of rivers or the sea, they would often be left hanging until submerged by the tide three times.

In London, Execution Dock became infamous for such displays, often transforming into a gruesome tourist attraction. This led to complaints that the gibbet iron displays offended foreign visitors.

The Spectacle of Gibbeting

Gibbeting was often a spectacle because of its horrifying and gruesome display. It still attracted large and jubilant crowds, sometimes numbering in the tens of thousands.

However, living near a gibbet was far from a cause for celebration. The decomposing bodies left in the gibbet cage emitted a putrid smell. This often caused locals to shut their windows when the wind carried the stench their way.

The iron cages hanging from the gibbet were designed for maximum horror, twisting, swaying, creaking, and clanking eerily in the wind. This created an unsettling atmosphere.

One harrowing example of gibbeting involved John Breads, who murdered Allen Grebell in March 1743 in Rye, East Sussex. After Breads was hanged, his dead body was left to rot for over two decades in an iron cage on Gibbet Marsh. His skull was clamped within the headframe.

Bibbets remained in place for decades. The bodies inside were gradually consumed by insects and birds, eventually transforming into skeletal remains.

The macabre nature meant that these sites became not only landmarks but also infamous features of the landscape. Gibbeted criminals lent their names to nearby roads and served as morbid boundary markers.

The eerie design of gibbets, particularly the body-shaped iron cages, contributed to their unsettling presence.

Despite the intent to instill fear and deter crime, the practice of gibbeting evoked complex emotions in the public. There was a mix of fear and disgust as well as entertainment. However, the odd obsession with gibbeting would eventually decline.

Decline and Abolition of Gibbeting

By the early 19th century, the practice of gibbeting had gradually fallen out of favor, and public interest waned. At the same time, the laws behind the “Bloody Code” were being relaxed. Capital punishment was becoming less frequent.

The last known case in Scotland was that of Alexander Gillan in 1810. And in 1832, the final instances of gibbeting occurred when two men, William Jobling and James Cook, were ordered to be gibbeted for separate crimes.

However, their gibbets were removed not long after their erection. In the case of William Jobling, friends took down the gibbet. In James Cook’s case, officials intervened when chaotic crowds overwhelmed the scene and blocked the roads.

These incidents reflected changing attitudes towards the practice. They marked the turning point for the ultimate abolition of gibbeting.

In 1834, just two years after the incidents involving Jobling and Cook, the practice was officially banned by statute. This marked the formal end of this grim and gruesome method of punishment in England.

With the final repeal, records, and memories serve as the only reminders of this dark chapter in history.

References

Cockburn, J. S. “Punishment and Brutalization in the English Enlightenment.” Law and History Review 12, no. 1 (1994): 155–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30042825.

“Gibbet.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed July 20, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/gibbet.

Wright, Andy. “The Incredibly Disturbing Historical Practice of Gibbeting.” Atlas Obscura, October 11, 2016. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-incredibly-disturbing-medieval-practice-of-gibbeting.