Gilles de Rais was a French nobleman who murdered over 100 children before being imprisoned and executed on October 26, 1440. His evil deeds made him the inspiration for the dark French fairytale Bluebeard, a story about a nobleman who uses his power and privilege to seduce and kill a series of wives.

In the fairytale, the villain’s seventh (and last) wife stumbles upon a room filled with the mutilated corpses of Bluebeard’s past victims. With the help of her brother, she manages to get away and even marries her “prince charming.”

Unfortunately, the historical inspiration for the tale is much darker. The real Gilles de Rais didn’t leave so much evidence in plain sight. Instead, he burned the bodies of the children that he killed and hid their ashes around his vast properties.

But how did this one-time companion of Joan of Arc and a hero of France become a child killer?

Perhaps more importantly – should we believe everything we hear about him?

Gilles De Rais Had a Troubling Childhood

It’s logical to start our exploration of the life of Gilles de Rais with his childhood because he was introduced to death and tragedy very early on.

At just ten years old, he witnessed his father die in a hunting accident where a wild boar gored him. Then, just a few months later, his mother died.

Suddenly an orphan, that meant that left Gilles de Rais with a vast estate, converting him into a powerful French noble.

The downside was that he was forced to live with his sadistic grandfather, Jean de Craon, who was well-known for his cruelty.

It’s impossible to say what kind of effect this turbulent childhood had on the young Gilles de Rais, but there are signs that already, as a child, he felt the stirrings of his later monstrous ways.

If his court testimony is to be believed, he spent much of his time alone as a child, leading to many opportunities in which he “pleased himself with every illicit act” and did “whatever evil he could.”

Aside from whatever emotional torment Gilles de Rais may have endured, there is no doubt that he was spoiled materially.

In just a few years, he turned into a vain and ruthless boy – a boy who also happened to be an armed knight. He quickly grew accustomed to combat, and by the age of fifteen, he had already made his first kill.

Gilles de Rais’ childhood did not last long. That phase of his life soon gave way to a new one when at the age of 17, he married Catherine de Thouars of Brittany.

Their marriage was problematic from the start. Gilles de Rais seems to have already been experiencing homosexual tendencies, and he and Catherine took seven years to produce a child.

Just as the baby was born, Gilles de Rais abandoned his wife and newborn child and never looked back.

Becoming a hero

Gilles de Rais may have been a terrible father, but if there was one thing he was good at, it was fighting and killing. Before he withdrew to his country estate and began his murderous spree, Gilles de Rais was best known for his heroism during the Hundred Years’ War.

Crucially, he was with Joan of Arc at the siege of Orleans, a turning point in that stage of the war.

It’s unclear what his relationship with Joan of Arc was really like or if they had any connection beyond being on the same battlefield. But his exploits in the battle (they broke a months-long English siege after just eight days) helped him to be appointed as marshall of France, the highest military honor that could be bestowed on a French noble.

Gilles de Rais and His Crimes

If there is a high water mark to Gilles de Rais’ career, it would be when he assisted Joan of Arc during the Hundred Years’ War. Conversely, her death marked the beginning of a downward descent that would end with his brutal killing spree and eventual hanging in 1440.

According to court documents, Gilles de Rais carried out the systematic abduction, rape, and murder of over one hundred children between 1432 (a year after Joan’s death) and 1440. But it was not until he assaulted a priest in September of that year that anyone came forward to denounce his crimes.

When the first witnesses came forward to accuse the French nobleman, they all had a similar story: their sons had disappeared in or around La Suze, one of Gilles de Rais’ properties.

All of these children had spent some time with de Rais; one even claimed that he had been forced to drink white wine during one of his visits.

We don’t know what happened to these boys, but based on the numerous testimonies that followed, we can create a pretty clear picture of de Rais’ methods.

First of all, he was not acting alone. He had at least two servants who helped him acquire and kill his victims.

According to their damning depositions, these servants would scour the countryside searching for young boys they could pry away from their parents.

They did so by promising that the boys would have a better life under the guidance of de Rais in his lavish castle. Some parents even volunteered to give up their sons, believing they would benefit from the tutelage of the wealthy nobleman.

Over time, the parents would have come to suspect the fates of their missing children. But it was not until the trial in 1440 that they realized the truly horrific end that befell their children.

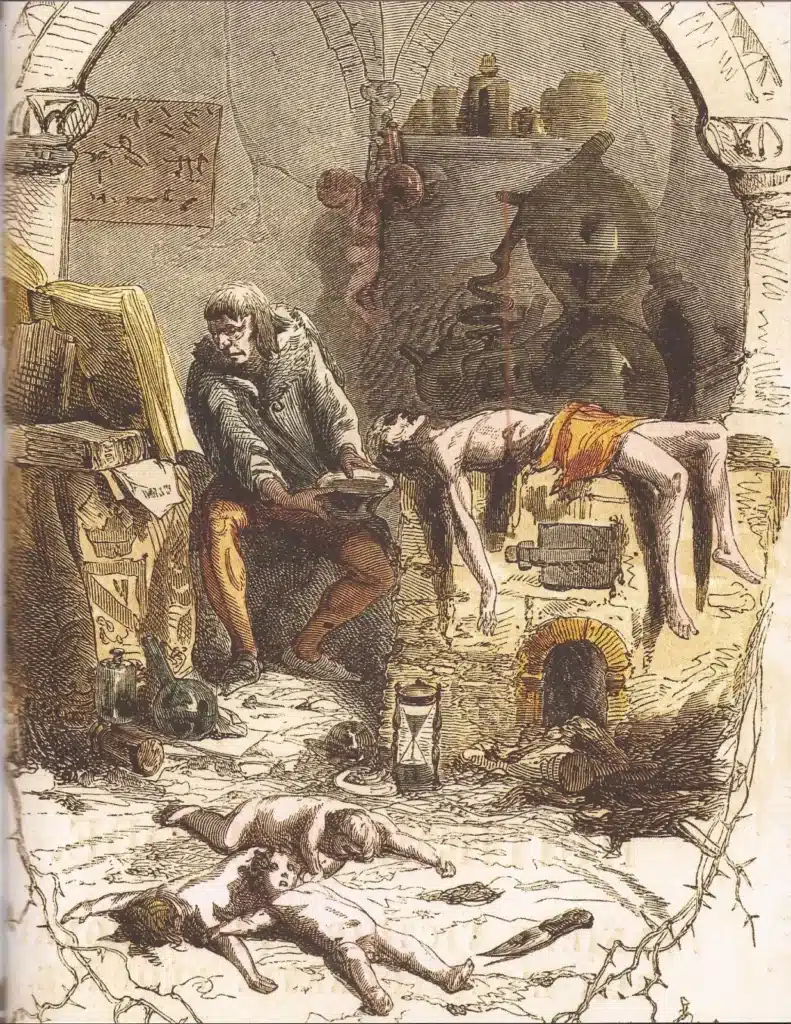

Gilles de Rais had one particularly sinister method that he repeatedly used in killing his victims. It was a method that he used to prevent them from making noise:

“To prevent their cries, and so that they would not be heard, the said Gilles de Rais sometimes hung them by his own hand, sometimes had others suspend them by the neck, with ropes or cords, on a peg or a small hook in his room; then he let them down or had them let down, cajoled them, assuring them that he did not want to hurt them or do them harm, that, on the contrary, it was to have fun with them, and to this end he prevented them from crying out.”

While their necks suspended them, he would then take out his penis and masturbate on their bellies. When finally done with them, he would take them down and finish them either by decapitating them, slitting their throats, or breaking their necks.

According to one of his servants, de Rais seemed to take special pleasure in the killings. He would sometimes sit on the boys’ bellies after slitting their throats to gaze at them as they died.

It’s not clear exactly how many children were killed in this way. One of his servants estimated that there were between 36 and 46 victims, but other estimates put the figure at well over 100, perhaps as many as 600.

By the time of the trial in 1440, Gilles de Rais’ heinous acts would have been going on for years.

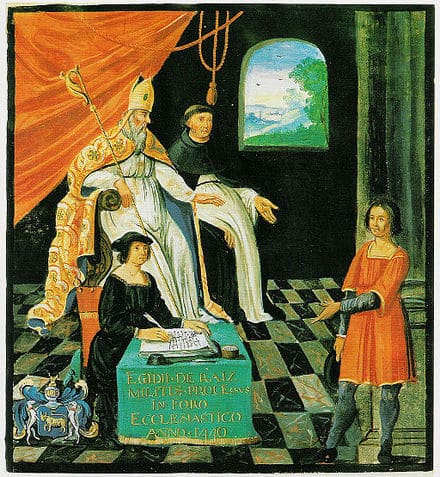

The Trial and Execution of Gilles de Rais

It may seem strange that Gilles de Rais was originally charged with assaulting a priest rather than for the cruel murders that so many peasants attributed to him.

But in the late medieval period, nobles enjoyed a level of privilege that largely protected them from the denunciations of peasants. If Gilles de Rais had never assaulted the noble priest, it’s tempting to imagine that his crimes may have gone unpunished.

But as things played out, de Rais’ death came relatively quickly. The overwhelming abundance of evidence against him gave him no way out. Nor did he try to deny the charges.

Instead, possessing a flair for the theatrical, he responded with dramatic passion to each of the judge’s questions.

When the judges pressed him about his motives for killing, Gilles de Rais at one point shouted, “Alas! Monsignor, you torment yourself and me along with you … Truly there was no other cause, no other end or intention … I’ve told you greater things than this and enough to kill ten thousand men!”

Finally, on October 26, 1440, Giles de Rais was hanged along with two servants who had personally helped in the killing of their master’s victims. After being executed, the bodies were burned and the ashes were disposed of. It seemed like justice had been done.

But was Giles de Rais truly guilty?

Gilles de Rais’s Contested History

From reading the trial transcripts on their own, it’s difficult to come away with any other conclusion than that Giles de Rais was a psychopathic serial killer. But some historians have questioned the validity of his trial.

For one thing, the Duke of Brittany, who had overseen the secular phase of the trial, acquired the legal titles to Gilles de Rais’ properties after his death.

At the very least, that shows a clear conflict of interest. Or it could show that the trial was a concerted effort to rob Gilles de Rais of his lands.

Other historians make a case for de Rais’ innocence based on the nature of medieval trials. Back then, a variety of grisly torture methods were used to get the accused to confess.

The threat of torture no doubt would have been on Gilles de Rais’ mind as he sat before the judges. He may have confessed just to avoid the arguably worse fate of being tortured or to prevent his excommunication.

This was the conclusion that a judge came to in 1992 when a French arbitration court of lawyers, historians, and politicians decided to conduct a rehabilitation trial to determine if the original trial had wrongfully convicted him of his crimes.

Among the reasons in his favor, no bodies of children were ever found in his castles, and his confession to the crimes came only after he was threatened with excommunication.

We may never know the true nature of Gilles de Rais and his supposed crimes. But that won’t stop historians from investigating this murky chapter of French medieval history.