Today’s architectural marvels are because of technology, equipment, and years of study in architecture and engineering.

But how do you explain the great architectural wonders of the past? They didn’t have the technology or the academic knowledge but they still made some awe-inspiring structures that have stood the test of time.

An excellent case in point is the Göbekli Tepe.

What Is Göbekli Tepe?

In Turkish, Göbekli Tepe means “belly hill” because it has a rounded top that reaches 50 feet, contrasting greatly with the nearby plateaus.

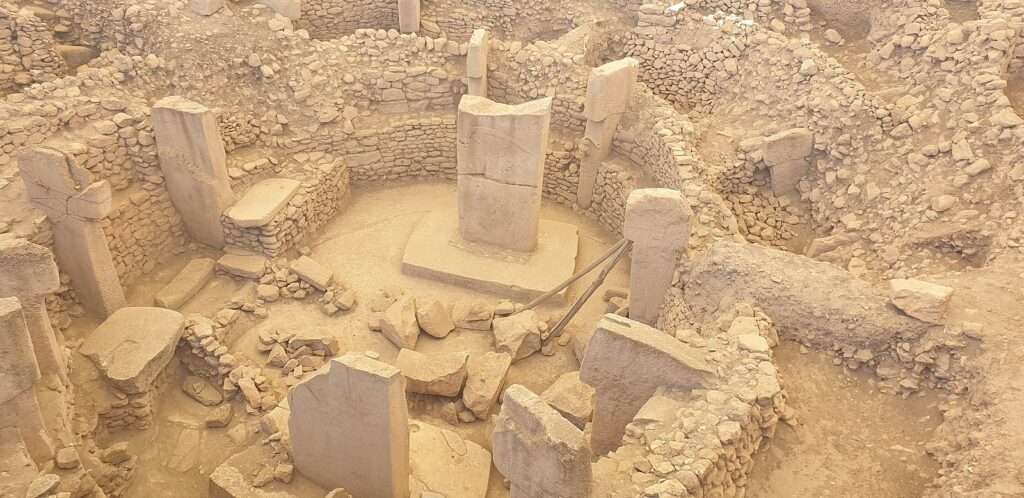

It is considered a Neolithic archeological site in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey. The large circular structure consists of several pillars that have interesting decorations and drawings. They depict the culture of the people who once lived in the area.

The stone pillars from the site are said to be the oldest megaliths or undressed stones used in monuments during the Neolithic (9000-3000 Before Common Era or BCE) and Bronze Age (3300-1200 BCE).

The structure spans about eight hectares with its highest peak reaching 15 meters. The space is densely populated with smaller structures that tell the story of ancient Turkish civilization.

Göbekli Tepe was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2018 for its cultural importance. Part of the declaration states, “Göbekli Tepe is one of the first manifestations of human-made monumental architecture. The site testifies to innovative building techniques, including the integration of frequently decorated T-shaped limestone pillars, which also fulfilled architectural functions.”

Discovery

German archeologist Klaus Schmidt led excavation teams at two sites in 1995:

- Gürcütepe – four shallow Neolithic tells in Urfa, Turkey. The team discovered that it was a rural settlement much younger than the Göbekli Tepe. It wasn’t significant enough to preserve and is no longer visible since it has been covered by modern buildings.

- Göbekli Tepe – the site stands on a limestone plateau in the foothills of the Taurus Mountains. It was significant because of the many smaller structures that supported the momentous transition when humans went from being hunters and gatherers to farmers.

The late Schmidt was convinced that the site was the world’s first temple. Work continues in the area even after Schmidt died in 2014.

As of 2022, there have been eight excavation works at the Göbekli Tepe which doesn’t even cover 10% of the whole area. In a 2008 interview, Schmidt said that even after 50 years of digging, we would still have barely scratched the surface of what’s buried at the Göbekli Tepe.

There was no proof that people lived in the area, which prompted him to conclude that it was a place of worship—a “cathedral on the hill” if you will.

Schmidt wasn’t the first to discover Göbekli Tepe but he was the first to see its potential. According to the Smithsonian Magazine, anthropologists from the University of Chicago and Istanbul University surveyed the area in the 1960s. They mostly assumed that the mound was a medieval cemetery because of the broken slabs of limestones in the vicinity.

However, archeologists have different sets of eyes. Schmidt did a similar sweep of the area in 1994 and immediately recognized something extraordinary. He read the University of Chicago report and decided he wanted to know more.

Noting the potbelly shape of the mount, Schmidt said: “Only man could have created something like this. It was clear right away this was a gigantic Stone Age site.”

Based on radiocarbon dating, the Göbekli Tepe’s earliest structures (at least those that were left exposed) were built between 9500 and 9000 BCE which is at the end of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A or PPNA (10000-8800 BCE).

It supported Schmidt’s theory of Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) because of the stone tools found during the excavation. Further, experts have said the site was expanded around 9000-8000 BCE.

What Göbekli Tepe Says About Ancient Civilization

Some of the tools found in the area were hammers and blades. Schmidt said the sloping rocky hills of the area were a stonecutter’s dream.

His theory was that the Neolithic people in the area used flint tools to chip away at the softer limestones to create pillars. These pillars were carried a few miles to the summit before they could be erected. The uncovered pillars formed circles. Around 200 pillars were found on the site.

Most of the pillars have beautiful and unique markings on them. Some depict animals like lions, boars, snakes, gazelles, vultures, and more. Some of the pillars also illustrated human activities that were presumed common in the PPN era. Since writing was invented around 3400 BCE, markings and drawings were the only way the ancient inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe could tell their stories.

Some of the pillars’ etchings showed figures with arm-like features. Meanwhile, the lower halves of the structures had drawings of loincloths. Interestingly, they were headless. Hypotheses of what these figures might be include respected ancestors, supernatural beings, and anthropomorphic objects.

The PPN is said to mark the beginning of village life as the Ice Age came to an end.

While some argued that the Göbekli Tepe could have been an ancient village, the absence of artifacts like cooking amenities, cooking hearths, and even remnants of houses made him believe otherwise. Nearby sites were littered with home artifacts and clay fertility figurines that were believed to be common during that time.

Neolithic Skull Cult

In 2017, the Göbekli Tepe diggings discovered more artifacts that told stories of ancient rituals. Researchers found bone fragments in the area and analyzed them.

The results, which were released in 2018, suggested that skulls may have been prominently displayed at the Göbekli Tepe. This provided a picture of how the community treated their dead.

Academics believe that the fossils are evidence that people during that time and in that area practiced an Early Neolithic skull cult which involved displaying decapitated heads. The heads may have belonged to venerated elders or enemies who were killed on the spot.

Some of the skulls in the area held evidence that they were defleshed while others were modified. Still, some had been painted on. These different treatments add to the complexity of understanding early PPN civilization.

Hunting and Farming

Remember how some pillars at the site have images of animals? There is evidence that the society mainly depended on animals for sustenance. The most hunted animal was the Persian gazelle which is native to Turkiye.

This belief is based on the cut marks and splintered edges on animal bone fragments found at the site. Archeozoologist Joris Peters from the Ludwig University in Munich studied about 100,000 bone fragments, 60% of which were gazelle bones.

Peters concluded that the main livelihood at that time was hunter-gatherers after he found thousands of animal bones that were presumed to be wild. This means that the community didn’t domesticate or farm animals.

In his published article, Peters also noted the other animals that became part of the diet of people who used to frequent the Göbekli Tepe area:

- Asiatic wild ass

- Deer

- Hare

- Fox

- Various bird species

- Wild boar

- Wild cattle

- Wild sheep

There is little evidence of farming, which doesn’t discount the idea that people were starting to plant crops at the time. No storage facilities for crops were found and there were no remains of edible plants.

However, wild einkorn, wheat/rye, and barley are common in the area. This means cereal production cannot be discounted as a farming activity which could have started the transition from hunting to farming.

Feasting

The ancient civilization seemingly loved to feast.

Peters and three others wrote in Göbekli Tepe: Agriculture and Domestication that hunter-gatherers from various parts of Anatolia and northern Syria would get together on the site to share their knowledge of hunting while gorging on freshly hunted meat.

The gathering would also touch on innovative techniques for monitoring wild ungulates, a certain type of hoofed mammals.

It may also be through these gatherings that a wider audience discussed the possibility of finding other ways to make food-gathering more sustainable since hunting posed risks of depleting the nearby supply of wild animals.

Archeologists found proof of a prehistoric village that corralled sheep, cattle, and pigs some 20 miles away from Göbekli Tepe. There is sufficient evidence that people started domesticating animals by then.

There were also some domesticated strains of wheat within the area. It could be evidence that people feasted with beer during that time.

The Göbekli Tepe seemed to have been abandoned by its inhabitants sometime in 8000 BCE. However, modern historians and academicians, aside from archeologists and anthropologists, continue to learn more about the ancient civilization in Turkiye.

Göbekli Tepe

Göbekli Tepe is Turkiye’s oldest archeological site. In 2021, around half a million people visited the site, enduring the long walk under the heat of the sun.

But many believe that the journey to see a structure that’s over 11,000 years old is worth it. It predates Stonehenge and the pyramids by thousands of years.

Digging started on the site as early as 1996 but less than 10% has been uncovered. There is more to learn about Göbekli Tepe and every dig opens up new discoveries about our past.

Perhaps when digging is past 50%, archeologists and anthropologists will learn more about our Turkiye ancestors.