Social scientists and philosophers have long argued that “god” is nothing more than a construct of the primitive human mind. A result of the fundamental need to explain the unexplainable.

But could it be that a specific area of the brain is responsible for triggering spiritual and religious thoughts? Could humankind’s relationship with “god” be part of an evolutionary, survival mechanism?

While science may not be able to definitively answer these questions at present, researchers have uncovered what they think is evidence that religiosity and a belief in god/gods are hard-wired into our brains. The question is: Why?

Defining God

“God,” in concept and existence, is perhaps the most debated, discussed, and philosophized topic in modern human history.

Philosophers, theologians, scientists, mathematicians, psychologists, historians—and members of a dozen of other academic disciplines—maintain a fascination with a phenomenon that in reality has no actual proof of existing. Yet, the fascination continues.

“God,” in concept, while virtually impossible to define in terms acceptable to the broad range of perspectives, is typically perceived as a superhuman or supernatural being that controls the world; everything and everyone in it.

But even this super-simplified, seemingly innocuous definition is contradicted when you consider that Roman Emperors, Egyptian Pharaohs, and British Kings have all been worshiped as “superhuman.”

The highly revered philosopher Baruch Spinoza equated God with Nature (thus completely “natural”). And famed Greek philosopher Epicurus denied that any god can influence the lives of men.

Thus, even in concept, “god” is difficult to identify.

As regards “god” in existence, the three primary monotheistic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), agree that four specific divine attributes are present.

- Omniscience

- Omnibenevolence

- Omnipotence

- Eternal/Everlasting

But here again, in that these traits are impossible to quantify and do require faith to accept as true, the existing god is no more definable than the conceptual.

Yet amazingly, whenever the reference “god” or “God” is used, virtually everyone understands the inference—even if their perspective differs. In essence, the concept of “god” or “God” appears to be universal.

This has led many scientists to believe that the notion of religion, spirituality, and “god” must be hardwired into our brains. Perhaps even embedded in our DNA.

The “Religious Experience”

The so-called “religious experience” is a term typically applied by the scientific community to individuals who have undergone a personal interaction with the supernatural (god, angel, celestial being). This involves elevating mere faith one step further: to what adherents believe is a private, even personalized encounter.

Some individuals experience visions. Others, reassuring voices. Almost all perceive “a presence” or sensation of “being one with the universe.”

These encounters typically bring about a catharsis, a sense of serenity, or even a euphoric state of mind to the individual. Many liken it to an epiphany; or a “close encounter” with god.

Still, others report a variety of other sensations including overwhelming emotions, a feeling of floating, and transformations of the physical body. And specifically religious, dreamlike hallucinations.

And while the accounts of these encounters can be quite compelling, they lack the elements of scientific credibility. Particularly, objective reproducibility.

The adherent may even acknowledge that his/her belief may not be scientifically justifiable, but that they nonetheless know it to be true due to the personal religious revelation they experienced.

Many are immovable in their conviction based on their belief that they were singled out for this special supernatural encounter.

On the Road to Damascus

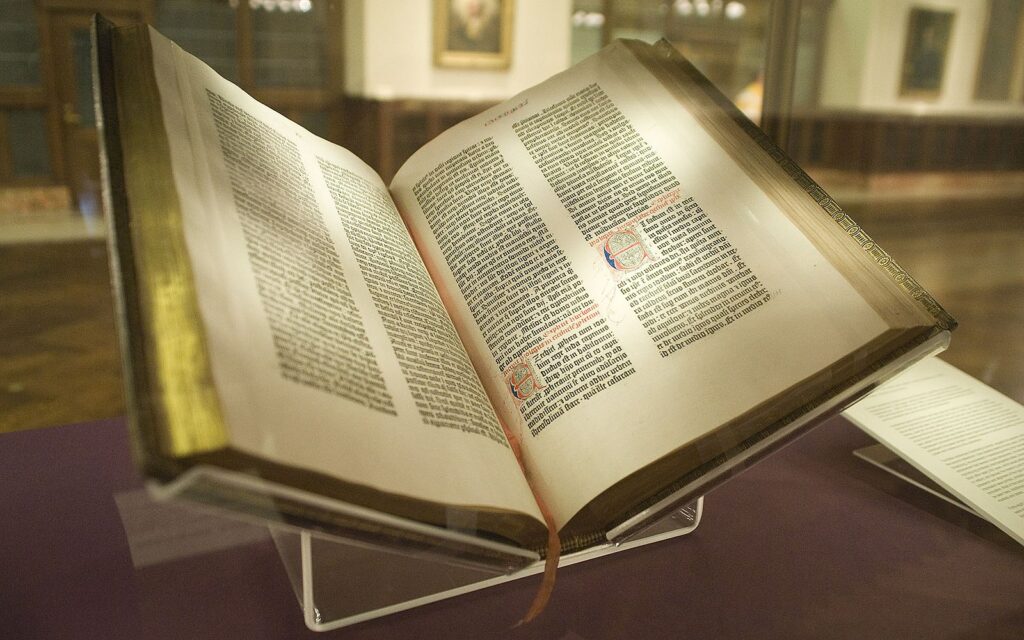

The most frequently cited example of the so-called “religious experience” can be found in Acts of the Apostles 9:1-9, in the New Testament of the Holy Bible. It recounts the dramatic conversion of Saul (Paul of Tarsus), the infamous Jewish persecutor of Christians, who encountered Jesus while traveling the road to Damascus:

“As he journeyed he came near Damascus, and suddenly a light shone around him from heaven. Then he fell to the ground, and heard a voice saying to him, ‘Saul, Saul, why are you persecuting Me?’

And he said, ‘Who are You, Lord?’

Then the Lord said, ‘I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting. It is hard for you to kick against the goads.’

So he, trembling and astonished, said, ‘Lord, what do You want me to do?’

Then the Lord said to him, ‘Arise and go into the city, and you will be told what you must do.’

And the men who journeyed with him stood speechless, hearing a voice but seeing no one. Then Saul arose from the ground, and when his eyes were opened he saw no one. But they led him by the hand and brought him into Damascus. And he was three days without sight, and neither ate nor drank.”

Assuming that something extraordinary did occur that day on the road to Damascus, (something not attributable to mental or physical illness), researchers in the fields of psychology and neuroscience have for decades searched for an explanation or rationale to explain what happened.

They now believe they’ve hit on the most logical answer.

The Epilepsy-Ecstasy Connection

In the mid-1990s, a group of neuroscientists were studying the brain waves of certain individuals with epilepsy.

This team of neuroscientists at the University of California at San Diego, led by neuropsychologist Dr. V. S. Ramachandran, stumbled upon a region of the human brain that appears to be linked to thoughts of spirituality and prayer.

In October of 1997, Ramachandran presented his team’s findings at the annual conference of the Society for Neuroscience in a presentation titled, “The Neural Basis of Religious Experience.” The press quickly dubbed the area of the brain in question, the “God Module.”

For over a century before these findings, psychologists had been documenting cases of epileptics. These people suffered from a specific kind of seizure associated with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). They became intensely religious, reporting spiritually-oriented visions and revelations.

This established a long-standing notion that epilepsy and religiosity must somehow be linked. But it wasn’t until recently that science had the technology to watch and measure the brain during such events.

By measuring the electrical activity in the brains of test subjects during such episodes, scientists have discovered that a specific neural center of the temporal lobe fires up when subjects’ thoughts turn to god; the same area that becomes overloaded with electrical discharges during TLE seizures.

Researchers won’t speculate as to the full range of functions attributable to this area of the brain. But they suspect it is some sort of physiological center of religious belief.

To further test the “God Module” theory, studies were conducted comparing epileptic subjects with random test groups of non-epileptics. They also included individuals who describe themselves as “extremely religious.”

Test subjects (both epileptic and non-epileptic “religious”) were shown a series of words while their brain activity was monitored. As presupposed, the “God Modules” of the epileptics, as well as the religious identifying group, exhibited comparable emotional arousal to words relating to god and faith.

Conversely, test groups shown a non-religious series of words (including sexual and violent), exhibited normal levels of electrical activity in this particular area of the brain.

What Might Be the Ultimate Function of the “God Module”?

Social scientists have long assumed that spirituality/religiosity developed as a self-regulating mechanism to encourage tribe loyalty and reinforce kinship ties. And the “God Module” presents the first evidence that religious instinct may be part of our physiological, survival makeup.

But considering that religion has for centuries been as divisive as unifying, has it exceeded its function? Or might there be another, greater purpose?

Theories regarding a greater purpose for the “God Module” focus primarily on the known functions of the temporal lobe itself. This area of the brain works in conjunction with the other regions of the brain.

But researchers think it is significant that the part of the brain known to play a key role in specific functions such as future planning (including self-management and decision-making), forming long-term memories, feeling empathy, regulating reward-seeking behavior and motivation via dopamine secretion, selective attention, and speech and language should also be the center of religious revelations.

Particularly in light of the fact that the temporal lobe essentially creates mini seizures in the brains of even healthy people to create so-called “religious experiences.”

Researchers speculate that any number of unapparent positive effects may result from temporal lobe-induced religious experiences.

For example, experiencing an interaction with “god(s)” or “supreme beings” is likely responsible for inspiring the human species to survive periods of famine, drought, pestilence, and a long list of other catastrophic events—natural and otherwise.

Also, when temporal lobe events occur, individuals who might normally sink into a schizophrenic stupor find focus. They continue to build, plan, and maintain hope—despite their mental illness.

Even in modern times, the probability of finding similarly-oriented religious adherents makes moving city to city, state to state, or country to country less daunting.

Are We All Predisposed to the Effects of the “God Module”?

Results thus far suggest that the level of development of the brain’s temporal lobe electrical circuitry may determine an individual’s tendency to follow a given religion or believe in “god” (or some “higher power”).

Those individuals who describe themselves as “non-religious” and never undergo a “religious experience,” could simply have a differently configured temporal lobe neural circuit.

Interestingly, there are many historic figures believed to have undergone spiritual transformation following an epileptic seizure. Examples include the Apostle Paul, the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel, Saint Bridget of Sweden, the Patron Saint of France Joan of Arc, and Saint Teresa of Ávila. They were all known to be religious-oriented before their “religious experience.”

References

ActforLibraries.org., “What is the God Module,” http://www.actforlibraries.org/what-is-the-god-module/

Spilka, B., et al., The Psychology of Religion, The Guilford Press, N.Y., 2003.

James, William, The Varieties of Religious Experience, Barnes & Nobel Books, 2004.

CenterforInquiry.org., “Searching for God in the Machine,” https://cdn.centerforinquiry.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/26/1998/07/22155908/p54.pdf

AnnualReviews.org., “Psychology of Religion,” https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.001221

Philosophyalevel.com., “Overview—the Concept of God,” https://philosophyalevel.com/aqa-philosophy-revision-notes/concept-of-god/

Encyclopedia.com., “God, Concepts Of,” https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/god-concepts

AltheistEmpire.com., “God and the Brain,” Atheist Empire: God and the Brain