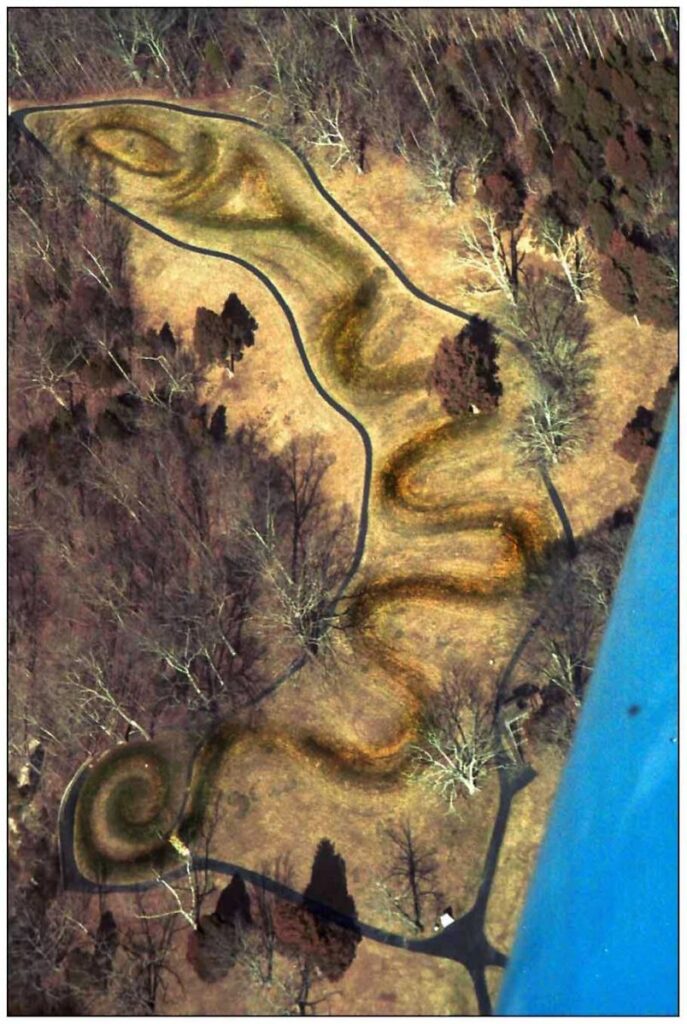

The Great Serpent Mound is an ancient earthworks site located in present-day Ohio. This effigy mound is over a quarter of a mile long, up to twenty-five feet wide, and five feet tall.

It’s the largest serpent effigy ever discovered.

Effigy mounds were common in the Mississippi Valley. Other surviving examples have been found in the shapes of wildcats, bears, deer, and birds. Some mounds were used as burial places, but nothing and no one has been found to have been interred in the clay used to construct the Great Serpent Mound.

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley

The Great Serpent Mound was first documented in Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley: Comprising the Results of Extensive Original Surveys and Explorations by Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis.

Davis was born in Ohio in 1811. He became increasingly interested in the earthworks and mounds that he encountered there throughout his youth. Squier was born in 1821 and became intensely interested in the mounds when he moved to Ohio in his twenties.

The book published in 1848 includes 48 maps and 207 sketches. The Great Serpent Mound is perhaps the most well-known of the sites that they studied. Other sites include Fort Ancient, Mound City, and Newark Earthworks.

The Great Serpent Mound was excavated by Frederic Ward Putnam a few decades later, but no artifacts were discovered within that that could connect it to a particular culture. Little is known of the people who constructed it.

Many ancient monuments in Ohio were being destroyed in the 1880s to make way for agricultural fields. In 1886, a group of wealthy women in Boston helped Putnam raise enough money to purchase the land upon which the Great Serpent Mound was located (along with three burial sites and the remains of an ancient village).

In 1900, ownership of the land was passed to the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society.

The Age and Origins of the Great Serpent Mound

Originally thought to have been constructed as many as three thousand years ago, more recent archaeological research suggests that it was built as recently as 1200 AD.

Radiocarbon dating in 1991 suggested that the mound was approximately 900 years old, but further research in 2014 suggested a link to the Adena culture that disappeared nearly two thousand years ago.

Archeologists are still unsure of when it was built. However, the popular consensus is that it was constructed approximately 2200 years ago by the Adena culture (800 BC to 1 AD).

It is speculated that it was later restored by the Fort Ancient culture (1000 to 1750 AD). This would explain the vast disparity in age suggested by different radiocarbon datings of the mound.

There are nearby burial mounds from both of these cultures.

The Adena Culture

This ancient culture was centered in Ohio but also included parts of Kentucky, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.

The Adena Culture was neither entirely hunter-gatherer nor fully agricultural, but somewhere in between. They were semi-itinerant, moving often to stay near herds of large animals, but also cultivated crops such as goosefoot, sunflower, maygrass, squash, knotweed, sumpweed, and tobacco.

They lived in dwellings constructed from timber and roofed with bark. They were possibly the first culture in the area to make and use clay pottery.

Adena peoples buried their dead in prominent mounds that were often over twenty-five feet tall and sometimes as many as three hundred feet tall. There were hundreds of these mounds at one point, but most of them were destroyed by farmers in the 1800s.

Sometime around 1 AD, the Adena culture gave way to the Hopewell culture. The Fort Ancient culture came later.

Fort Ancient Culture

This culture takes its name from the Fort Ancient archaeological site in Ohio (which was, somewhat ironically, originally built by Hopewell peoples). The Fort Ancient people lived there centuries later.

The earthworks at Fort Ancient were the work of many generations, built in at least three stages over the course of four centuries. Digging sticks were used to loosen the soil along with tools made from split elk antlers, clam shells, and the shoulder blades of deer.

Baskets with a capacity of up to forty pounds of earth were used for transport as these people moved over half a million cubic yards of soil.

These massive walls had 84 gateway openings and were probably not built for defensive purposes. In other words, Fort Ancient wasn’t actually a fort. Archaeologists believe that the walls’ purposes were social, economic, political, and ceremonial.

The Fort Ancient culture occupied this site and others in settlements of up to five hundred people. Their dietary staples were beans, maize, and squash. They also hunted black bears, turkeys, deer, and elk.

The Serpent in American Indian Traditions

While the purpose of the Great Serpent Mound has been lost to history, we can glean clues from the beliefs of other native peoples who inhabited the area later on, whose beliefs and traditions were influenced by those of earlier peoples.

In many belief systems, the Great Serpent was a powerful spirit who could heal the sick and grant good fortune to hunters. The Shawnee believed that Grandfather Serpent ruled the World Below. Some archaeologists believe that the peoples of the Mississippi Valley used snakes to represent the heavens.

At the front of the serpent’s undulating body is a gaping mouth poised to swallow a huge oval. Scholars cannot agree on what this oval represents, or even if we’re looking at a mouth swallowing an oval at all. Some have interpreted this oval as the eye of the snake.

Some scholars have argued that the oval represents the sun, and the snake swallowing the sun represents a solar eclipse. Others say that the undulating shape of the snake mimics a certain constellation. The oval may have been used as a ceremonial platform.

The true significance of the Great Serpent Mound may never be discovered, but it remains as an enduring piece of American history. The site is open to the public and has been submitted for consideration as a World Heritage Site.