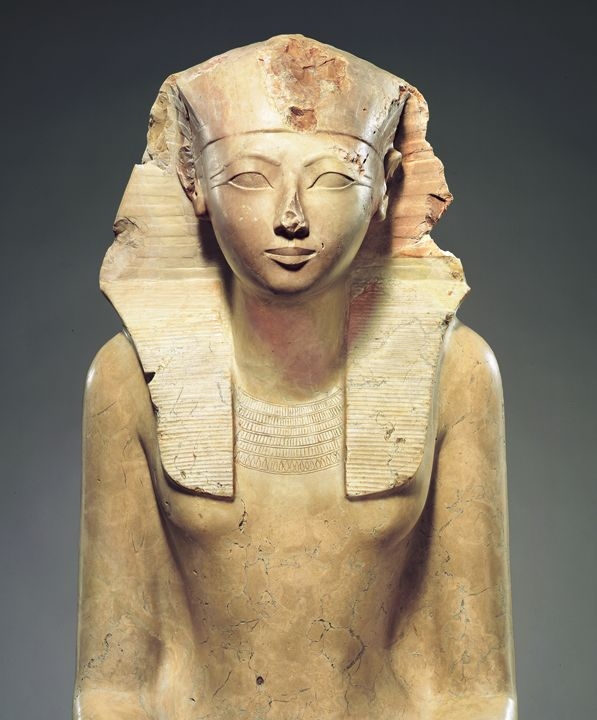

Hatshepsut ruled Egypt for thirty-five years in the fifteenth century BC. First, as the Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Thutmose II and then as Pharaoh in her own right.

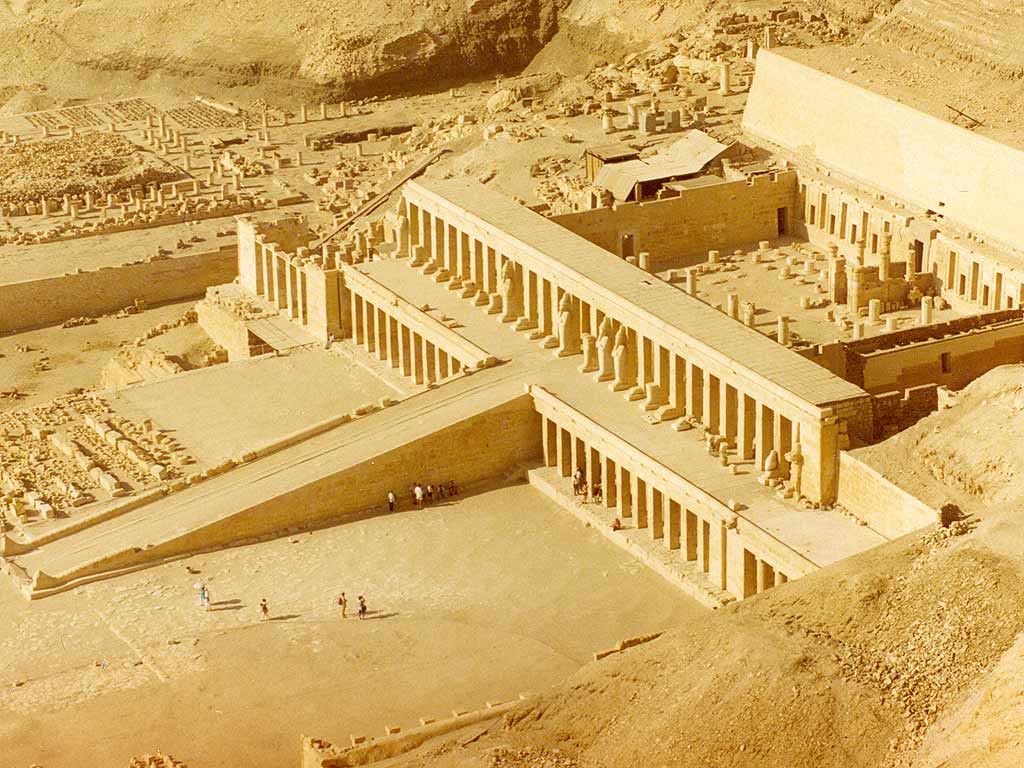

The Temple of Hatshepsut is a mortuary temple built during her reign.

Constructed roughly a millennium after the Great Pyramid of Giza and over four hundred miles upriver, this monument of upper Egypt represents an entirely different era.

Great Royal Wife

Hatshepsut was the daughter of the Pharaoh Thutmose I, who reigned for thirteen years. Her grandfather, Amenhotep I, reigned for twenty.

Amenhotep revolutionized the design of mortuary complexes by creating a tomb that was separate from his mortuary temple. This was a practice that Hatshepsut continued during her time as Pharaoh.

Thutmose II and Hatshepsut were the two surviving children of Thutmose I.

Hatshepsut was the daughter of his Great Royal Wife, Queen Ahmose. Ahmose was a member of the royal family in her own right, most likely the aunt or sister of her husband Thutmose I.

Thutmose II was the son of a minor wife named Mutnofret. While Egyptians were generally monogamous, the Pharaoh commonly had lesser wives and/or concubines.

To strengthen their claim to the throne, their father arranged for Thutmose II and Hatshepsut to marry in their mid-teens. Hatshepsut became the Great Royal Wife, an important and active role in Egyptian culture.

She also became God’s Wife of Amun. This meant that she was the highest-ranking priestess of the king of the gods.

Thutmose II died when he was thirty years old. His body was interred in the Deir el-Bahari Cache near the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut.

Pharaoh Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut was the first woman to take up the title of Pharaoh.

At the time of Thutmose II’s death, his heir Thutmose III was only two years old. Thutmose III was the son of a lesser wife or concubine. His aunt and stepmother Hatshepsut became regent. A few years later, Hatshepsut dropped the pretense and became a fully-fledged Pharoah.

She claimed that her father had intended for her to rule. An inscription carved into the walls of the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut reads:

Then his majesty said to them: “This daughter of mine, Khnumetamun Hatshepsut – may she live – I have appointed as my successor upon my throne… She shall direct the people in every sphere of the palace; it is she indeed who shall lead you. Obey her words, unite yourselves at her command.”

The royal nobles, the dignitaries, and the leaders of the people heard this proclamation of the promotion of his daughter, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkare—may she live eternally.

Hatshepsut’s Reign

She reigned as Pharaoh for over twenty years, up until her death around the age of fifty. She worked with Thutmose III during this time, and he served as a military commander once he came of age.

Hatshepsut had one child with Thutmose II, a daughter named Neferure. She was highly educated. Eventually, she was entrusted with important political and religious roles.

When Hatshepsut took on the traditionally masculine role of Pharaoh, her daughter assumed the responsibilities typically associated with the Great Royal Wife.

Neferure’s titles included Lady of Upper and Lower Egypt, Mistress of the Lands, and God’s Wife of Amun. Some scholars believe that she married her brother Thutmose III and bore his eldest son. Others think that she died towards the end of Hatshepsut’s reign.

During her reign, Hatshepsut oversaw an era of prosperity and growth. She established new trade routes and commissioned hundreds of construction projects. These projects included several new temples, monuments at the Temple of Karnak, and the restoration of a temple dedicated to an ancient goddess.

The greatest of all of her building projects was the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut.

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

This enormous temple is located near Luxor. Construction began in the seventh year of Hatshepsut’s reign and was completed near the end of her life, the plans having undergone several revisions over the years.

The temple was built primarily of limestone, augmented in places with red granite and violet sandstone. Massive ramps led from one terrace to another.

These areas were lined with statues and adorned with flowers in the early days, when the temple was in use. Over one hundred sphinxes lined the path to the temple.

The mortuary cult complex has two offering halls: one dedicated to Thutmose II, and one for Hatshepsut. Hers is the largest chamber in the whole temple.

The purpose of these chambers was to provide a place for people to make ritual sacrifices and other offerings to the deified Pharaohs after they died, thereby nurturing their souls in the next life.

Hatshepsut’s tomb was separate from the temple, but it was built into the same cliffs. It sat beneath a massive peak that acted as a sort of natural pyramid.

There were shrines dedicated to the goddess Hathor and the gods Anubis and Amun. Hatshepsut was depicted everywhere, feeding Hathor in some places and appearing as Hathor reborn in others.

In Amun’s temple, Hatshepsut named him as her father. Images depict her and her daughter making offerings to the god.

Priests at the mortuary temple conducted daily rituals to purify the temple with incense and prayer. They also made daily offerings to the gods. Once the gods had taken in the essence of the food, the earthly banquets were consumed by the priests.

Other rituals involved the singing of hymns and the destruction of clay or wax figures representing enemies of Egypt.

The Beautiful Festival of the Valley

Amun’s temple was the final destination of the Beautiful Festival of the Valley. This was an annual celebration and major holiday in Thebes (modern-day Luxor) that could go on for days.

It was held during harvest season during a new moon in the tenth month of their calendar year. The god Amun-Re was central to the celebration, which also included his consort Mut and their son Khonsu. Amun was the patron deity of Thebes.

The Beautiful Festival of the Valley was akin to the modern Mexican celebration of Dia de Muertos. It was a time to remember the dead and make offerings to them. Food, drink, and massive quantities of flowers were offered to the gods and to people who had passed on to the next world.

People brought food and drink to their deceased relatives, partied at their tombs, and then slept right there where their families were interred.

Each year, Hatshepsut led the procession from East to West – the land of the rising sun and life to the land of the dead. Along with her nephew Thutmose III, she led a flotilla of nobles and priests from the Eighth Pylon at Karnak across the Nile to various cemeteries.

Then on to the temple of Amun, where they would present the god with a great banquet.

Rewriting History

Long after Hatshepsut died – towards the end of her nephew’s reign and into the reign of his heir Amenhotep II – efforts were made to erase Hatshepsut from the historical record.

In the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, her statues were torn down. Many of her statues were smashed with sledgehammers before being thrown into a pit or nearby quarry.

Her name was chiseled off of the walls and replaced with the name of her brother or father. In other places, her name was plastered over.

The motivation for this vandalism is unclear. The Pharaohs who followed her may simply have been seeking to take credit for the great works of architecture built during her reign.

Like his father and grandfather, Amenhotep II was the son of a lesser wife. He may have been working to strengthen his claim to the throne by claiming these monuments as his own.

This trend of insecurity was not limited to Hatshepsut. Amenhotep II refused to memorialize the names of his wives or the high priestesses of his time.

While Hatshepsut’s name was replaced in many places and the feminine words scratched out, in other parts of the temple the usurpers didn’t bother to change words from the feminine forms to their masculine forms. This created a puzzle for historians that led to the discovery of Egypt’s earliest female Pharaoh.

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut was damaged further during the reign of Akhenaten. He ordered that images of Egyptian gods be destroyed as part of his campaign to impose a monotheistic religion upon the Egyptian people.

Much of this damage was repaired during the time of Tutankhamun and subsequent Pharaohs.

In the third century, during the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, the middle terrace held a stone chapel built in honor of the Greek god Asklepios. Another Ptolemy altered the temple of Amun and converted it into a shrine for an ancient architect and the goddess Hygieia.

The temple housed a monastery in the seventh century, and the original reliefs were painted over with images of Jesus Christ. It was excavated in the nineteenth century, restored in recent decades, and finally opened to the public in March 2023.