Last updated on September 14th, 2024 at 01:53 am

Born as a slave in the early 1800s, Henry “Box” Brown escaped from enslavement and became a well-known abolitionist and stage performer.

His escape is notable for both its creativity and gutsiness. He mailed himself to freedom in a crate, earning him his nickname. Today, he is an icon in African-Americans’ fight for freedom.

Early Years

Henry Brown might have been born in 1815 or 1816 at Hermitage, a plantation near Yanceyville in Virgina’s Louisa County. He spent his childhood with his parents, three brothers, and four sisters. They were all slaves of John Barret, Richmond’s former mayor.

After Barret’s passing on June 9, 1830, Brown had to leave his family and travel to Richmond. Upon reaching his destination, he worked for Barret’s son, William. The son owned a tobacco factory where Brown ended up working as a slave.

Meanwhile, Brown’s siblings were shipped to other plantations with the exception of his sister Martha whom William Barret kept as his mistress.

Family Life

By 1836, Brown met and wed another slave named Nancy, who was owned by another slaver. Together, they had three children.

His family became members of the First African Baptist Church’s congregation. Brown joined its choir.

Brown was a skillful worker at the tobacco factory. He often worked long hours to bring home enough income so that his family could live in a rented home.

In August of 1848, Nancy’s master sold her along with her children to a North Carolina slaver while she was pregnant.

Distressed at being physically separated from his wife and children, Brown mourned for several months. It was then that he decided to fight for his freedom. But the task demanded a creative and ingenious plan.

He approached James Caesar Anthony Smith, a fellow choir member, and a free man. James Caesar Anthony helped him get in touch with Samuel Alexander Smith, a white bootmaker and an occasional gambler who occasionally helped enslaved workers. Alexander Smith relented and agreed to help Brown flee in exchange for money.

Together, the trio brainstormed ways that would allow Brown to escape. Brown suggested that he would ship himself from Richmond to Philadelphia in a crate that would transport him by rail.

Settling on the plan, they managed to reach out to James Miller McKim. McKim was a leader of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia and was connected with the Underground Railroad.

During the 19th century when slavery was prevalent, the Underground Railroad was a network of safe houses and secret routes that people used to escape slavery. It was established by African American slaves in an effort to gain freedom.

Escape to Freedom

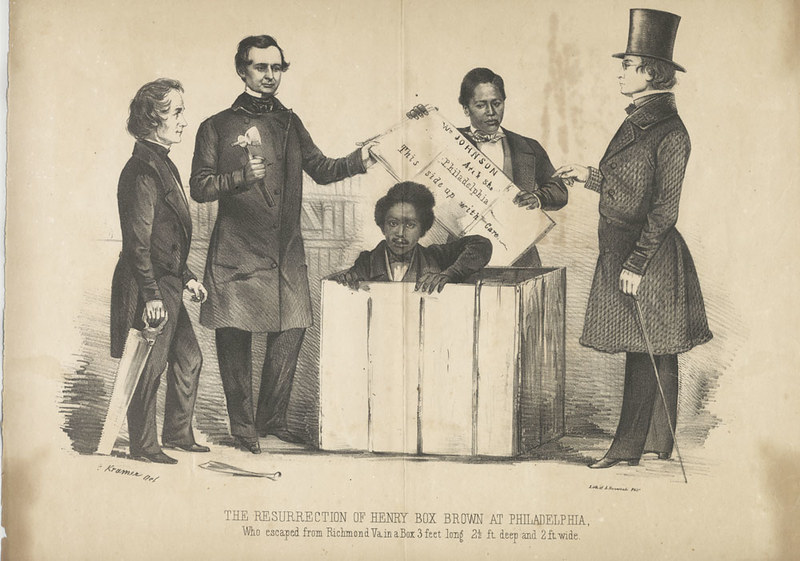

On the 23rd of March, 1849, Brown fitted himself inside a wooden crate. Since it was for shipping, it was small and cramped, measuring only three feet in length, 2 feet in width, and two-and-a-half feet deep. The two Smiths labeled the box “dry goods” and shipped it to Philadelphia.

When the crate was transferred to a steamboat, it was placed upside down for many hours. This proved almost fatal for Brown as his eyes swelled to a point that it felt as if they would pop out from his skull. Because of his awkward position, the veins in his temples also bulged as blood rushed to his head.

Fortunately, his agony finally ended when a man repositioned the box right side up and sat on it with a friend.

By the early morning of the next day, the package reached McKim at the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society office in Philadelphia. Upon opening the box, Brown emerged from his twenty-six-hour confinement and recited a psalm. It was then that he earned his name Henry “Box” Brown.

Life as an Abolitionist

Two months later, Brown attended the New England Anti-Slavery Convention in Boston. He sang the psalm he recited upon being released from the small box.

At the convention, people celebrated his escape. To raise attention to and reinforce the fight against slavery, Brown began regularly attending and reciting psalms at abolitionist meetings.

Impressed by his story, doctor and author Charles Stearns wrote and published a memoir of Brown’s daring escape. The pair traveled across New England to sell the volume entitled Narrative of Henry Box Brown and deliver anti-slavery lectures until November 1849.

Though Brown was lucky to have escaped bondage, this wasn’t the case for everyone.

On May 8, just a few months after Brown was shipped to Philadelphia, Samuel Alexander Smith attempted to free another group of slaves by shipping them. Unfortunately, his attempt was discovered and led to his apprehension. Later that same year, he was convicted and sentenced to six and a half years in prison.

The other Smith, James Caesar Anthony Smith, also helped Samuel Smith, but he managed to evade capture until September 25, 1849. The panel that decided his fate had divisive opinions and this enabled him to avoid being imprisoned.

Brown as an Artist

In late 1849, Brown hired artists like Josiah Wolcott to create a moving panorama about bondage. Entitled Henry Box Brown’s Mirror of Slavery, it was released in Boston on April 11, 1850. It was exhibited in New England all summer long.

Before long, the Fugitive Slave Bill threatened the freedom of African American slaves who had escaped. If it became legislation, it would allow governments to seize former slaves who had fled to freedom and return them to their owners.

Because of mounting tensions caused by the bill, Brown was assaulted in Providence, Rhode Island. Fearing that he might be enslaved once again, he traveled to England with James Caesar Anthony Smith in October 1850.

This allowed them to exhibit Brown’s panorama from November 1850 until the spring of 1851 in Liverpool, Manchester, Lancashire, and Yorkshire. In May 1851, Brown published his autobiography in Manchester. He simply called it The Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown.

Brown’s Life After James Smith

In that same year, Brown and Smith quarreled bitterly over money, leading to the end of their partnership. Smith also felt that Brown wasn’t trying hard enough to buy the freedom of Nancy and his children.

In retaliation, Smith wrote letters condemning Brown to well-known American and English activists. This prompted Brown to move away from activist groups and enter show business.

He continued developing his panorama and began performing as a hypnotist in 1857. He would entertain audiences by showing them how he could induce different people into doing strange things while being hypnotized. He also staged performances as an African Prince and would go inside the original box he was shipped in as part of his show.

At one point, he filed a libel case against a newspaper that printed racial slurs about his performances and he won.

Despite the many unique challenges he faced, Brown lived a full and remarkable life. In 1859, he remarried and had a daughter. He spent his last days with his family in Toronto before passing away on June 15, 1897.

Over 100 years later, Brown’s escape from slavery has inspired many artworks, plays, a short film, an opera, and a wax museum exhibit.