Last updated on July 22nd, 2022 at 07:25 pm

When a serial killer is caught, all their crimes come to light. The terror they committed in hiding is revealed, and the weight of their crimes is set against them. Some leave missing victims or resist their own convictions. Many, being cornered without escape, admit to the whole truth of their violence, even beyond what the police have come to learn was up to them. No serial killer is perfect. They all get caught eventually, usually because they end up killing too often.

But Henry Lee Lucas confessed to over 3,000 murders. Or so he claimed. His profile paints the picture of a man fully capable of violence of the highest, most grotesque order, but also of a pathetic man desperate for attention even at the cost of his own life.

“I hated all my life.”

Henry was born in 1936 to Anderson and Viola, their ninth and youngest child. Anderson was a laborer until a railroad accident took both his legs. From then on, Anderson became a moonshiner, making alcohol at the tail end of prohibition while turning to it to soothe his problems. Henry’s mother was no better. She was a prostitute and extremely abusive.

Henry was subjected to one of the worst childhoods one can imagine. He was beaten by both his parents interchangeably and his older brothers. He was hit so hard on the head that he passed out for three days and was given minimal medical care. His mother killed a mule given to him by an uncle and even hit him for bringing a teddy bear back from school he’d received as a gift.

She sexually abused him as well. As young as three, she dressed him as a girl and made him watch as she had sex with one of her lovers and clients. One of his half-brothers and uncles forced him into Beastiality. And during all of this time, he became a child alcoholic.

He gained his characteristic sunken left eye at the age of 11 when he got in a fight with his brother. The injury was left to fester until it was infected and could no longer be saved. He had a glass eye installed at just 11 years old. His bleak worldview was cut right in half.

In 1949, when Henry was just a teenager, his father died. That should have been the end of his torment, but the damage to his psyche was already done. At 14, he committed his first violent act. He abducted an unknown girl at a bus stop, beat her until she passed out, and strangled her to death. Or so he claimed.

The victim was named Laura Burnley, who disappeared around that time, but Henry’s words were never taken with credibility. Mostly because he changed them from time to time, his story lacked the consistency of a repentant or unrepentant murderer. If true, it was the start of a truly gruesome criminal history. If not true, and he merely imagined doing such a thing, or took credit for it just for the sake of feeling powerful, then it was the start of something possibly worse.

Legal Troubles

Henry first got into real trouble with the law in 1952, a year after Laura Burnley’s missing status was upsold to a murder, but he wasn’t in trouble for that. Instead, he was sent to a juvenile delinquent school after he and his brothers committed a burglary. However, prison seemed to suit him better.

The prison had running water. And electricity. Rare glimpses of civilization that Henry was refused for so many years. It was paradise by comparison. The one-room log cabin he grew up in was his real prison, a tight space where all the evil he was subjected to couldn’t pour out and miss him. Perhaps that was an impetus for his future actions. The promise of such order and privilege, and all he had to do was hurt others. Or, at least, claim to.

His next arrest was for a dozen counts of burglary. His life was low when he wasn’t stealing. His crime spree lasted until 1954 when he was sentenced to six years of incarceration but was released in 1959. After that, he tried to move on to new fields. Or new victims. That’s when his mother showed up.

Viola was still alive and ailing. She was old and sickly and wanted him to take care of her. A child of abuse, he couldn’t say no, and the abuse continued against him. It escalated to the point where they argued so bad he took a knife to her and stabbed her in the neck. She died of a heart attack as a result of the shock of her injuries. Henry pleaded self-defense but was convinced of second-degree murder and sentenced to 20-40 years in prison.

He was released in June 1970 due to overcrowding.

The One-Eyed Drifter

Henry only spent ten of his twenty-plus years in prison before being forced out. Not nearly enough time for any benefit. It was now the 1970s, a high time for serial killers across the nation, and Henry was determined to be one of them. He was sentenced to three and a half years almost immediately after being released for the attempted abduction of three girls.

After release, he moved to Pennsylvania and worked on a mushroom farm. He married a woman named Betty Crawford – formerly the wife of his cousin – in 1975, and things seemed to be evened out. If it left off here, it would have been the story of a man finding a middle road to a peaceful life.

Betty accused Henry of molesting her two daughters from her previous marriage. In time, these were crimes he owned up to, and he began to drift through the south. He did odd jobs and claimed to have a long string of unsolved murders, raping and killing women wherever he went. Then he met an accomplice: Ottis Toole, in Jacksonville, Florida. What could Henry bond over with another man?

Ottis Toole

It turned out Toole was also a self-acclaimed sexual deviant. Toole pulled Henry along with him to work at a roofing company and invited him to stay. During that time, Henry developed feelings for Frieda “Becky” Powell – Toole’s ten-year-old niece. Rumors abounded about Henry and Ottis that they were in a homosexual relationship, a taboo in the late 70s and early 80s.

They claimed together to enact over 100 murders in a short span of time. By Henry’s own account, Ottis was somehow the more depraved of them. He took orders through a Satanic cult, “The Hands of Death,” crucified his victims, then cooked and ate their flesh. While Toole confessed to murder, he never confessed to such a technique, and no evidence was ever found.

Henry didn’t like the choice of sauce, so he never partook.

The two murderers soon moved to Texas, along with Becky, who Ottis had more-or-less given to Henry as their relationship developed. However, Becky felt homesick, and on her wish, Henry simply left Ottis behind and ran away with his underaged bride. Ottis admitted to being so enraged that he spent a year stalking and killing nine people in six different states.

Meanwhile, Henry got a job in elderly care with Becky until they were found out to be fraudulently writing checks in their patients’ names. They fled to a communal home in a Pentecostal area where the head preacher gave them shelter in exchange for Henry’s skills in roofing. In August of 1982, Henry drove Becky to a field in Denton and killed her. He cut up her body and spread the pieces out across the field. Why?

So he could entice Kate Rich, the elderly woman the two of them took care of, to help look for Becky. When she agreed to go with him, he killed her in Ringgold, Texas, on a camping ground and stuffed her body in a drainage pipe.

Then he returned to the House of Prayer alone and free. Up to that point, he was never caught. When Kate Rich was reported missing, he retrieved her body and burned it in a stove at the commune. Being who he was and his connection to her, the police eventually called him in for a polygraph test – which he passed. What got him arrested and ended his freedom was illegal firearm possession charges. From there, the state charged him with the disappearance and death of Becky and Beth.

And so he told them all the rest, as he remembered it, which was slightly different from what they knew.

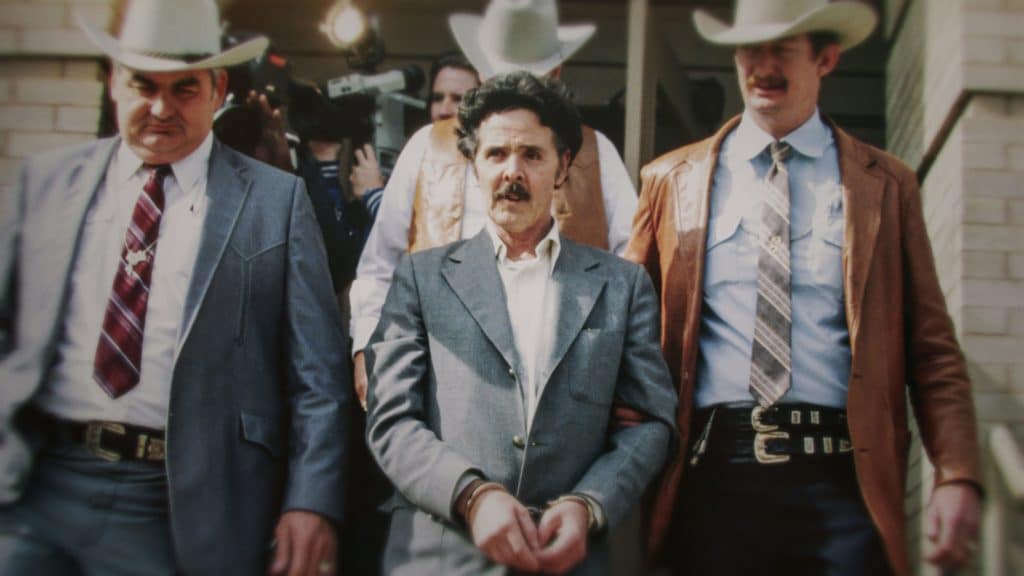

The Confession Killer

Henry’s confession came just four days after he was jailed. In his words, it was to “escape harsher treatment” by the Texas Rangers if he were to lie. And in court, he laid forth a further proclamation that these were just two of hundreds of murders he’d committed.

His confessions stemmed not just from his own murders, for which the police lacked solid evidence and proof beyond the production of human remains without identification. He confessed to every murder that he seemed to know about, combining them together with his own elaborate tales of how he did them. In a year, he confessed to hundreds of formerly unsolved murders, which required the formation of a “Lucas Task Force” to properly disseminate the confessions as real or not.

He confessed to a total of 213 murders by the time he was transferred to Williamson County, but he wasn’t done yet. He confessed to murders in Florida, Oklahoma, Georgia, Pennsylvania, Virginia – and every state department wanted to have a word with him on who he hurt and how he did it.

Henry was flown all over the country. Instead of going between jail cells, he was put up in motels. Instead of being starved, he was given steaks and milkshakes – whatever he wanted to keep his lips loose. He confessed to deaths that were already ruled on, such as Clemmie Curtis in West Virginia, which was ruled as a suicide. He was either the greatest killer mastermind in history or a farce.

A Dallas detective took a gamble and used his position with police to make up some crimes – total fabrications, with dates and discovery notes and autopsies, to see if Henry would slip up and confess to them as well.

Which he did.

A different detective did the same thing, and he claimed responsibility for those incidents as well. He insisted on the narrative of “The Hands of Death” cult working behind the scenes. He claimed to be the supplier who poisoned the Peoples Temple in Jonestown, and he committed murders in Japan and Spain. He even claimed to kill Jimmy Hoffa.

Eventually, there were more accusations for a year’s worth of murders than there were murders themselves. Finally, the media heard about it and started pulling the pieces together. Some of his confessions were physical impossibilities, requiring him to travel thousands of miles in a single day just to pull them off, and some when he was underaged. If he were telling the truth, he would have been stalking and killing almost daily from the time he was 13. He even confessed to the murder of someone who was still alive.

Portrait of a “Serial Killer”

Henry’s case became such a national sensation – first out of grotesque horror and then the sheer laudability of it – that it inspired the movie Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, which depicted himself and Toole as violent sociopaths, which wasn’t wrong. The most fictitious part of the film depicted him as the prolific killer he claimed to be.

The ruse was pretty much up at that point. It was obvious to law enforcement and everyone paying attention that he was just doing it for fame and freedom.

He was treated better as a confessed serial killer than he was as a wandering laborer. There was no way of telling just what he was honest about in his many deeds. Many cases were reopened or reclosed only to be invalidated by Henry’s impossible timeline.

The only thing to do was charge him, so the state of Texas was charged with nine murders, including ones from out of state that most closely matched his history of movements. Ultimately, he was sentenced to death for one crime, in particular, the “Orange Socks” murder, named after what the victim was wearing.

A murder he could not have committed yet admitted to regardless.

Henry eventually recanted many of his confessions, nearly all of them, in fact. However, he stood by three: his mother, Becky, and Kate. He insisted he was not a serial killer, as plainly and sensibly as he could. It was clear he was just in it for the attention. But in the end, his own lies broke him. Acting like a killer made him one.

His sentence was commuted to life in prison just six days before his execution, and he died in 2001 of a heart attack, leaving behind more than just death. He left behind a trail of upset graves of the deceased whose unsolved crimes were forced to stay buried. Though he was convicted of six additional murders, the methodology behind all of them differed too greatly to fit the profile of a “serial killer” as even he knew it.

Though he did admit to being a fairly poor one in the end.

His confirmed crimes were even more heinous, proving that his mind was not fully regular as he may have acted. He claimed to engage in necrophilia with Kate Rich’s body at least once while it was stuck in the pipe and did so with Becky’s body before dismembering it. He confessed that his modus operandi – the common method or trait that serial killers use for each of their victims – was any way except for poison, which itself contradicted his claim to have been the poisoner of the Jonestown cult.

The remainder of the victims in his list of convictions died in specific ways, nearly none of them similar in placement or delivery. Some were bound and shot. Others were simply shot, some stabbed many times or stabbed once and strangled, some sexually assaulted, some not – the inconsistency of it all led to a simple deduction.

Henry Lee Lucas wasn’t a serial killer. He was a disturbed man with a tortured childhood, which led him to a life of spreading abuse in a desperate search for comfort. He found comfort in punishment – in juvenile detention and prison – and sought it later in life, using his status as a “famous killer” to get special treatment for as long as he could.

But he was a killer, out of desperation or just sheer anger. In his own words, “I hated all my life. I hated everybody.” Yet, at least one person he killed, he claimed to have loved.