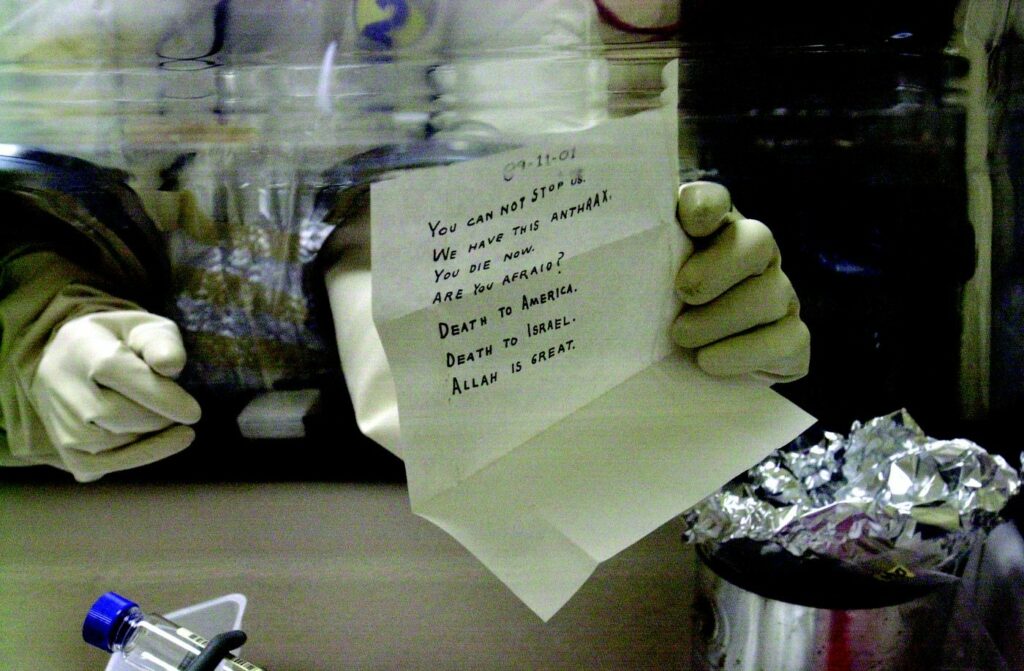

“You Can Not Stop Us.

We Have This Anthrax.

You Die Now.

Are You Afraid?

Death to America.

Death to Israel.

Allah is Great.”

These lines were written on the face of an envelope sent to Senator Patrick Leahy in the aftermath of 9/11.

Inside the envelope, the attackers stuffed a white powder that when inhaled causes symptoms ranging from coughing and fever to shock and death. It was one of four letters that caught the attention of the American public and stirred up fear and uncertainty in the weeks after the hijackings.

The identities of the perpetrators of these anthrax-laced letters remain unknown to this day, but the weapon they used is well known.

Having originated in Egypt and Mesopotamia, anthrax is found naturally all over the world. But beginning in the 20th century, with the help of scientific advancements, anthrax became a deadly biological weapon.

And as it turns out, the anthrax letters were just one shocking episode in the long and fascinating history of this deadly toxin.

Anthrax in Ancient Times

The history of anthrax goes back to the Bible. It’s mentioned as the fifth plague in the Book of Exodus.

This plague was described as a devastation to the Egyptians’ cattle and horse populations. It left its human victims with black spots on the skin – both symptoms that resemble what anthrax does to the body.

It’s also thought that anthrax was mentioned by Homer in The Iliad. He describes it as a “burning wind of plague” that afflicted the pack animals before moving on and affecting the soldiers that traveled with them.

The Roman poet Virgil similarly may have been talking about anthrax when he wrote about an epidemic that was so deadly it caused animals to rot in their stalls.

Anthrax may have been far more than a literary reference. It possibly shaped the fate of the Roman Empire.

In 165 AD under the reign of Marcus Aurelius, one of the good emperors, a plague swept through Rome and devastated the population. This deadly disease left its victims with fevers, cramps, and severe diarrhea. As the disease progressed, the afflicted person would develop black marks all over their body and some would even cough up scabs that formed inside of them.

This epidemic killed up to 10 percent of the 75 million Romans living in the empire. That massive death toll was not without its consequences. The severe die-off interrupted local government and led to a depopulated countryside. It even caused the military to cease many of its operations.

For years, scientists identified this horrifying plague as smallpox, brought back to Rome from Marcus Aurelius’ military campaigns against the Parthians. But based on the evidence, it’s possible that the real culprit was anthrax.

The history of anthrax pre-dates even these historical descriptions. It’s thought that anthrax originated 11,000 years ago when humans first started domesticating animals.

Since anthrax is primarily spread between animals, it makes sense that animal domestication would mark the beginning of human cases of anthrax. Since that time, cases of anthrax have been most frequent in places where animals and humans share an intimate relationship.

In the 1800s, Europe’s rapid industrialization meant that more and more animals started being clustered together to be processed in industrial operations. This left the people who worked with the animals at high risk of developing the disease.

Known then as “wool sorter’s disease” or “rag-pickers disease,” anthrax primarily affected shepherds, tanners, butchers, and wool workers.

Even in the 21st century, many countries with lax veterinarian services and a prominent animal husbandry sector see relatively high numbers of anthrax cases.

Fortunately, most countries today vaccinate their domesticated animals, which has dramatically reduced the global number of cases.

Developing the Anthrax Vaccine

The anthrax vaccine, like many other vaccines, is something that often goes unnoticed but protects us from what was once a very dangerous disease.

The road toward an anthrax vaccine began in Europe. Doctors like the parasitologist Casimir Joseph Davaine started noticing that animals who suffered from the so-called “wool sorter’s disease” showed rod-shaped organisms in their blood.

From that observation, Robert Koch was able to grow his own anthrax cultures and record their life cycle in the laboratory. Through his experiments, he was able to observe how anthrax developed and survived in different environments. This helped him perfect the culture techniques that Louis Pasteur previously developed.

While Robert Koch was identifying anthrax bacillus, Louis Pasteur was busy developing the world’s first vaccine. With the organism responsible for anthrax now identified, Pasteur decided to take things one step further in 1879. He started testing out an animal vaccination for anthrax.

He took 70 sheep and split them into two groups. He gave one group a low-strength culture of the disease, while he did nothing to the control group. Then he administered the anthrax bacillus to both groups.

As he had hoped, all of the vaccinated sheep survived while all of the sheep in the control group died.

Although a human vaccine for anthrax was not created until the 1950s, Koch’s experiments helped prove the efficacy of his vaccines and helped save the lives of countless animals.

Anthrax Becomes a Weapon

Unfortunately, the deadly nature of anthrax also means that in the wrong hands, it can be a potent biological weapon.

The anthrax scares in the years after 9/11 were a wake-up call to many people regarding the threat posed by biological warfare. But the truth is, anthrax has been used as a weapon as far back as World War I.

During World War I, Germans put anthrax into animal feed that was destined to be shipped to the Allies. At one point Norwegian police intercepted a German agent who was on his way to infect reindeer herds that the Allies used as meat.

In the war’s final year, up to 200 Argentinian mules were killed after ingesting feed-laced anthrax. However, it wasn’t until World War II that the use of anthrax was embraced on a large scale.

The Japanese first used anthrax during their invasion and occupation of Manchuria from 1932 to 1945. To test the effectiveness of the chemical, the Japanese tested the substance on prisoners of war including both American and British prisoners. It is estimated that up to 10,000 prisoners died as a result of the experiments.

But it wasn’t just the Japanese who saw the potential of anthrax as a weapon. The British were also studying it as a possible offensive weapon for decades.

Paul Fildes was the man who ran the secret British facility tasked with developing biological weapons during World War II. Even before the war broke out, he was planning a possible wide-scale anthrax attack on Germany.

To test the effectiveness of his anthrax bombs, he released some of them onto the British island of Guinard in 1942. Of the 15 sheep that the researchers exposed to the bacteria, 13 of them died, clearly demonstrating its potency.

As the war proceeded, this so-called Operation Vegetarian became more of a possibility. In anticipation of the biological attack, Fildes had 5 million linseed-oil cakes made. Each of these was laced with anthrax.

The plan was to drop the cakes over Germany with the hope of killing any cattle that ate them. However, due to an Allied victory and the development of nuclear weapons, that plan was never implemented.

Research into weaponized anthrax continued during the tense years of the Cold War. Although nuclear weapons took the center stage in the global arms race, the Soviet Union also carried out extensive research into anthrax.

In 1979, this research ended in tragedy when anthrax spores leaked out of a biological weapons plant in the town of Sverdlovsk. This resulted in the deaths of at least 64 out of the 96 people who were infected.

In the United States, President Richard Nixon banned the manufacturing of anthrax and other biological weapons in 1970.

Two years later, an international agreement known as the 1972 Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, and Stockpiling of Biological and Toxin Weapons was put forward. It was signed by Great Britain and a group of Warsaw Pact nations.

However, anthrax would see a deadly resurgence just a couple of decades later.

That brings us back to the anthrax letters. Although only five people died from the attacks, the amount of fear and speculation that they generated was enormous.

Envelopes filled with a powdered form of anthrax showed up at various media outlets and the offices of two Senators. This infected numerous mail workers and the employees of various publishing companies. In all, up to 10,000 people may have been exposed to the deadly bacteria from just four letters.

As news of the attacks waned, people gradually stopped worrying about anthrax. Pretty soon, other events took center stage. The news cycle continued. What seemed like a major threat to national security became eclipsed by new preoccupations.

The anthrax scare may be a decades-old event; but, as history shows us, it may not be the last time we hear about this deadly substance. The history of anthrax stretches far into the past, and unfortunately, it will likely continue into the future.