Dragons have captivated our imaginations for millennia, appearing in the myths and legends of cultures scattered worldwide.

From the fire-breathing beasts of ancient Greece to the dragon kings of Chinese mythology, dragons have long served as symbols of power, danger, and wisdom.

But where did the widespread stories of these fierce, fantastical creatures come from, and why have they captured our imagination for so long?

Ancient Mesopotamian Dragon Myths

Tales of dragons, as we recognize them, first appear in the mythology of ancient Mesopotamia. Turn back the clock to the 2nd millennium BC and a mythological creature called the Mušḫuššu, or fierce snake, appears in written texts.

The Mušḫuššu emerges throughout Sumerian and Babylonian mythology and is described as serpent-like, covered in scales, and possessing a snake’s tongue and head, along with the talons of an eagle.

Most notably, the god Marduk is often depicted as one of these dragon-like figures, which may also have represented the defeated deity Tiamat.

The draconic creature can be seen in carvings from the Ishtar Gate in Babylon, dating back to the 6th century BC.

It is uncertain where these dragon myths originated, but they spread throughout the region.

Dragons in the Lands of Persia

Dragons also appear in the literature and mythology of ancient Persia, particularly in the form of the Azhdahas – evil figures depicted as giant snakes or winged lizards. Zahhāk, also known as Zahhāk the Snake Shoulder, is one such figure in Persian mythology, also described in ancient Persian folklore, such as the Avesta, as Azhi Dahāka.

Meanwhile, in Zoroastrianism, one of the oldest religions on Earth, Zahhāk is considered the son of Ahriman, the personification of an evil spirit.

So clearly, while dragons feature heavily in ancient Persian mythology, they were considered beings of great evil and seen as bad omens.

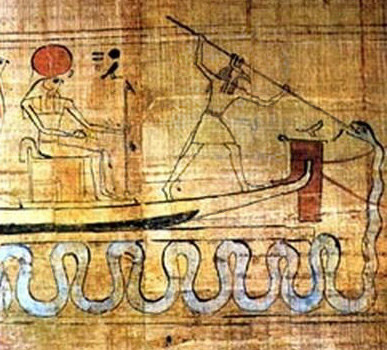

Ancient Egyptian Dragon God

Ancient Egyptian stories also host mythological dragons like the giant serpent deity Apep, or Apophis, who was viewed as the god of chaos and the adversary of light.

Apep was the nemesis of Ra, the Sun god, and his roots can be traced back to as early as 4000 BC.

The Chinese Dragon

The Chinese dragon is revered in its culture. The dragon has long symbolized power and good luck, as well as portending influence over the weather, not unlike in other cultures.

It is widely viewed as a spiritual and harmonious symbol in Chinese mythology. For example, the Chinese Emperor often used the dragon to showcase his power.

The earliest presentation of dragons in Chinese culture appears during the Xinglongwa era – 6200-5400 BC – while the traditional image of the dragon morphed and solidified later during the Shang – 1766-1122 BC – and Zhou – 1046 BC–256 BC – dynasties.

The concept of the Chinese dragon is famously presented through the “Dragon King of the Four Seas.” Each Dragon King is linked to a specific color and body of water.

For instance, the Blue Dragon represents the east and spring, with the Red Dragon symbolizing the south and summer, the Black Dragon the north and winter, and the White Dragon the west and autumn. Finally, the Yellow Dragon is considered the animal embodiment of the Yellow Emperor.

Dragons in Japan and Korea

Dragons are legendary figures in Japanese folklore and mythology. Their origin is a mix of native legends and myths imported from other Asian cultures, particularly China.

A handful of indigenous dragon stories in Japan, such as the Kojiki and Nihongi, emerged in the late 7th century AD.

Chinese dragons greatly influenced the appearance of Japanese dragons. They are large serpentine creatures with clawed feet. These creatures are typically associated with bodies of water, rainfall, and water deities.

Like the Japanese, Korean dragon mythology draws heavily from Chinese influence. However, in contrast to European folk traditions, the Korean dragon is a benevolent creature associated with water and agriculture.

In Korean legend, dragons are often depicted as conscious beings with emotions and are protectors of the country. The legend of King Munmu, who wished to become a dragon of the East Sea to protect Korea, is a famous example.

Dragons on the Indian Subcontinent

The Mahabharata epic is a significant text in Hindu mythology, and it introduces the concept of nagas or serpent beings. The epic describes the nagas as a semi-divine race with the power to assume human or serpent forms.

Naga kings, including Shesha, Vasuki, Takshaka, and princess Ulupi, are all depicted in the epic. They are often associated with the underworld and dark caves and depicted in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain iconography in various forms, including as humans with snakes on their heads or as half-human, half-snake beings.

Another large serpent in Vedic religion is Vritra, also known as Ahi, a dragon personifying drought and adversary to the thunder god Indra.

Southeast Asian Dragon Myths

In Philippine mythology, the Bakunawa is a dragon-like serpent creature. It is believed to bring about natural phenomena such as eclipses, earthquakes, rain, and wind.

The Bakunawa is usually depicted as having a looped tail and a single horn. It was generally considered a sea serpent but was also thought to inhabit either the sky or the underworld.

Over time, the Bakunawa became associated with the Hindu-Buddhist Nāga, Rahu, and Ketu, all other dragon-like creatures, through increasing trade and communication with other South Asian civilizations.

Similar versions of the water-dwelling dragon exist. In Tagalog and Ati mythologies, Laho, also known as Nono or Buaya, is another serpent-like dragon that causes moon eclipses.

And the Kapampangan Láwû is known to be depicted as a bird-like dragon or serpent that causes solar and lunar eclipses, with features closer to the Hindu-Buddhist demon Rahu.

European Dragons

Dragons play a significant role in ancient Greek mythology, depicting them as large snakes with the ability to spit or breathe poison. The word “dragon” is derived from the Greek word “drakōn,” which has its roots in the Latin word “draco,” meaning a large, constricting snake.

The ancient Greeks wrote of several serpent like creatures including Typhon, Ladon, the Hydra, and the Colchian dragon, meant to strike fear in the hearts of great heroes.

Germanic mythology also portrays dragons, known as “worms,” as large venomous serpents, with bat like wings. However, the distinction between Germanic dragons and regular snakes is often blurred in early depictions, with both referred to as “ormr” in Norse mythology or “wyrm” in Old English.

The evolution of wingless worms to flying dragons with four legs is likely due to influence from the rest of Europe, facilitated by the Christianization of the region in later years.

Dragons Among the Indigenous Tribes

Across the Atlantic, dragons also appear in the cultures of many Indigenous tribes throughout the Americas.

The Illini people painted murals of the Piasa Bird in the Mississippi River area, a winged dragon figure. Its presence isn’t quite understood, however, some believe it originates with the much larger Mississippian culture of Cahokia.

Elsewhere, in eastern North America, the Horned Serpent can be seen again and again in native cultures where it is most typically associated with the elements of rain and lightning.

The Feathered Serpent

Further south, among the civilizations of the Aztecs and Maya, the depiction of the Feathered Serpent is just about everywhere. First worshipped at Teotihuacan in the 1st century BC, the deity was originally depicted as an actual snake, however, over time this morphed into a figure also bearing human-like characteristics.

The Yucatec Maya worshipped Kulkulkan, while the later Aztecs worshipped Quetzalcoatl, both figures representing the feathered serpent, a foundational deity in the region’s mythology.

Andean Serpent Deity

Continuing further southward into the Andes of South America, mythical creatures also appear here. Associated with both the Incan and Tiwanaku empires, the amaruca was a mythical serpent, sometimes described as two-headed, associated with the underworld and the boundary between spiritual realms.

The amaruca could also be seen sometimes depicted as having the head of a bird and its wings, giving it even more of a resemblance to dragons. These sorts of serpent deities also extended the Mapuche peoples.

In Mapuche mythology, the figures of Ten-ten vilu and Kai-kai vilu were the serpent goddesses of the earth and of the sea.

Where Does the Dragon Myth Originate?

Draconic creatures that breathe fire appear in mythology and folklore worldwide, across centuries and millennia. Unfortunately, many of these stories also appear to have evolved completely independently of one another.

So where do these myths come from? And why is it that so many disparate civilizations have formed their own dragon tales?

Some speculate that our ancient ancestors could have been trying to make sense of fossil discoveries, like prehistoric dinosaur bones or ancient whale skeletons.

Others guess that these cultures based their myths on creatures they already knew – like Komodo dragons in Asia or the massive Nile Crocodile in Egypt.

Yet, in the end, we have no way of truly knowing how and why dragon legends play such a role in mythology, but it’s clear that they will continue capturing the hearts and imaginations of many, for generations to come.

References

Radford, Benjamin, and Callum McKelvie. “Dragons: A Brief History of the Mythical, Fire-Breathing Beasts.” LiveScience, 19 Jan. 2022, https://www.livescience.com/25559-dragons.html.

Rose, Carol. Giants, Monsters, and Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth. W.W. Norton & Company, 2001.

Schuyler, Stephen J. “What Dragons Look like around the World.” Grunge, Grunge, 15 July 2021, https://www.grunge.com/462238/what-dragons-look-like-around-the-world/.

Smithsonian Magazine. “Where Did Dragons Come from?” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 23 Jan. 2012, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/where-did-dragons-come-from-23969126/.

Stein, Ruth M. “The Changing Styles in Dragons—from Fáfnir to Smaug.” Elementary English, vol. 45, no. 2, 1968, pp. 179–89. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41386292.