Last updated on December 6th, 2022 at 04:45 am

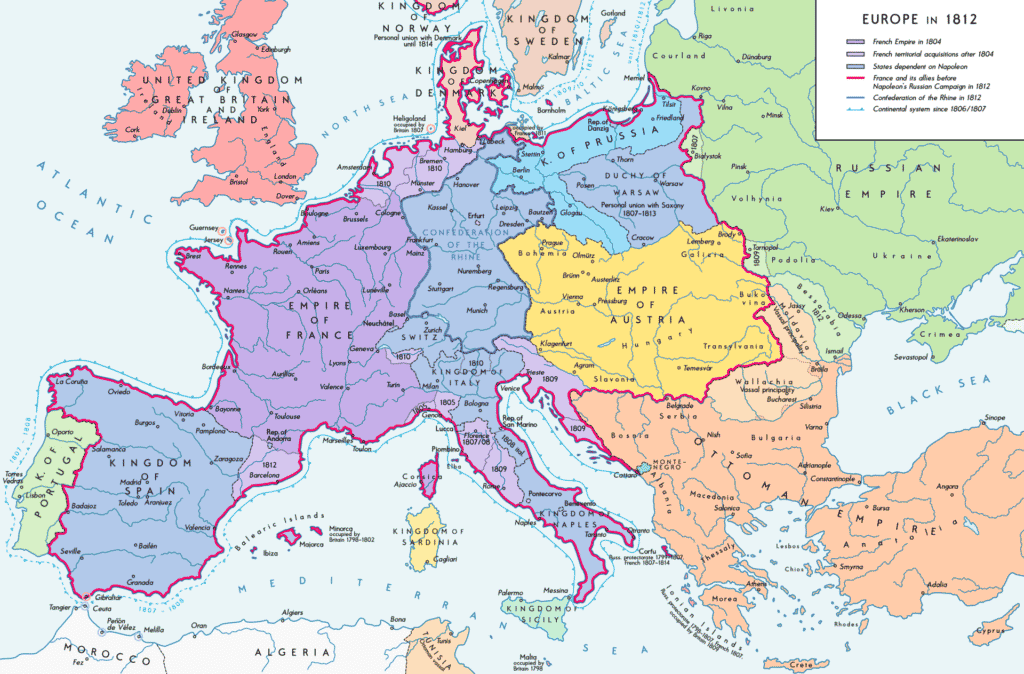

In 1807 the Emperor of France, Napoleon Bonaparte, might be said to have reached the pinnacle of his power. He had just defeated the two great nations of Central Europe, Austria and Prussia. Then, with the Treaty of Tilsit with Tsarist Russia, France became the dominant power in Europe.

The borders of the French Empire itself stretched into Belgium and the Rhineland of western Germany, while the kingdoms of Spain, Italy, and Naples were all under French control. Indeed Napoleon himself was King of Italy and his brother Joseph of Naples at that time.

Additionally, in Germany, Napoleon had effectively created the Confederation of the Rhine as a new entity under his rule and stripped Prussia and Austria of much of their lands to establish a new French vassal, the Duchy of Warsaw, in Poland.

Only Britain stood against Napoleon, protected by its fleet from the all-conquering French army. But, within less than a decade, it was all gone. Napoleon was living out his last years on the island of St Helena in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, and France’s monarchy was restored.

Given this, one might be tempted to think that all the bloodshed and war had been for nothing. And yet this is not entirely true, for Napoleon’s conquests changed European history enormously.

The End of the Holy Roman Empire and German Unity

Perhaps the most tangible way Napoleon changed Europe’s face was by redrawing Germany’s political map.

Since the High Middle Ages, Germany had been divided into hundreds of political entities, ranging from large duchies such as Baden and Bavaria to small palatines or even independent imperial cities.

What tied all of these together was the Holy Roman Empire, an umbrella organization created during the medieval period and overseen by an emperor elected by various electors from within the empire.

It was evident long before the French Revolution that the Holy Roman Empire’s day was over and its purpose limited. Large states such as Prussia and Bavaria no longer paid the Austrian House of Habsburg, which had monopolized the imperial office for centuries, much mind.

Napoleon, though, was the one who finally brought it to an end, dissolving the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, over a millennium after it was created.

After the Napoleonic Wars, many of the smaller principalities and cities were absorbed into the larger German states so that by the mid-nineteenth century, there were just a few dozen German states.

This made unifying them into a German Empire much easier for the Prussian statesman Otto von Bismarck in the 1860s and early 1870s. Consequently, Napoleon played a major role in creating the modern German state.

The Napoleonic Code

Perhaps greater significance than events in Germany was Napoleon’s extension of the Napoleonic Code throughout much of Europe. This was based on the French Civil Code, which evolved from the French Revolution.

This contained many measures we take for granted in modern democratic nations but which existed almost nowhere in the world in the early nineteenth century except for the United States.

For instance, the Napoleonic Code guaranteed people who lived under its freedom of religion and equality before the law. But, at the same time, it also abolished the hierarchical system of society, dividing people into the commons and the aristocracy.

This meant, for instance, that serfdom was abolished anywhere that the Napoleonic Code was introduced. Many people in countries outside of France might have disliked foreign rule under Napoleon.

Still, it was only after he was removed from power and his law code was revoked in many places that people realized exactly how lucky they had been. Fortunately, in the decades that followed, many of the freedoms granted under the code became staples of European life.

The Rise of Democracy and Nationalism

The spread of the Napoleonic Code was responsible in significant ways for changing political ideas across Europe. And this, in turn, impacted the country’s political landscape later in the nineteenth century.

In 1848 a series of revolts broke out across the continent against the monarchies and imperial regimes of countries like France and Austria. The ideas of the French Revolution inspired these revolts over half a century earlier.

Many of those same revolutionary ideas had been carried to other parts of Europe due to Napoleon’s conquests. So the spread of democratic principles was a by-product of Napoleon’s conquests. So too, was the growing nationalism of the nineteenth century.

This led to the independence of countries like Belgium, which finally became a nation-state in 1830 after over three centuries of Spanish and Austrians domination.

By that time, there was also an Italian nationalist movement inspired by the country’s union as the Kingdom of Italy during Napoleon’s days.

Establishing the Politics of Nineteenth-Century Europe

The Napoleonic conquests and the peace agreements reached at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 also established the political landscape of Europe for much of the nineteenth century.

By 1815 the major powers of Western and Central Europe, France, Austria, and Prussia, were bruised and battered from over twenty years of nearly perpetual war.

Conversely, Britain had escaped direct damage. The French had never invaded it. Thus, much like how the devastation that the Second World War inflicted on Europe allowed for the rise of the United States as the major western power post-1945, the Napoleonic Wars facilitated Britain’s rise as the superpower of the nineteenth century.

By contrast, France, Britain’s rival for power in Western Europe throughout the eighteenth century, was massively weakened in the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars.

The Crumbling of the Spanish Empire

Finally, perhaps the most important ways in which the Napoleonic conquests changed history lay beyond the borders of Europe altogether. In 1808 Napoleon removed King Ferdinand VII from the throne of Spain and made his brother Joseph the king of the Iberian nation.

This action sparked a series of revolts across the vast Spanish colonial empire in Central and South America. At first, these refused to cooperate with the Napoleonic regime in Madrid. Still, by 1810 a series of full-blown wars of independence from Spanish rule broke out in places like Mexico and Argentine, inspired by the earlier examples of the American War of Independence and the formation of the United States.

And what was more, these wars did not stop when Napoleon was removed from power in 1815, and the traditional Spanish monarchy was restored. Rather they intensified as figures like Simon Bolivar extended the wars into Gran Colombia and Peru.

It was a long, drawn-out process, but in the late 1810s and the early 1820s, Spain effectively lost all of its colonial possessions from California south to Tierra del Fuego as the beginnings of the modern nations of Latin America emerged.

This was probably the most significant, though the accidental route in which Napoleon’s conquests changed history.