Last updated on January 29th, 2023 at 11:34 pm

In the early spring of 1637, the madness surrounding tulips reached its height in cities like Amsterdam. For years there had been a growing obsession with the flowers, which are native to Central Asia and believed to have only been introduced to Europe through the Ottoman Empire in the mid-sixteenth century.

However, by the mid-1630s, the fondness for these bulbs had become so acute that it is often termed a ‘mania,’ ‘fever,’ or ‘craze.’

In February 1637, it peaked as people began trading the flowers in Amsterdam for sums equivalent to a year’s wages for a skilled craftsman. And then the bubble collapsed. This story is about how tulips created the world’s first economic bubble.

The Dutch Republic Started the Tulip Craze

The context in which this would occur is essential. In the seventeenth century, the Dutch Republic was the most advanced economy in Europe. This was primarily based on its dominance of the carrying trade of the North Atlantic.

For instance, if goods arrived in a port in Western Europe from Sweden, Finland, or the region lying along the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, it was almost sure that they had arrived on a Dutch ship. The largest company in the world (and all of human history) was the Dutch East India Company.

This mercantile power allowed cities like Amsterdam and Rotterdam to flourish and what is known as the Dutch Golden Age, a blossoming of Late Renaissance art into the Baroque, to occur in what was otherwise a relatively small corner of the European continent.

Indeed, so significant was the Republic’s economy that economic historians, generally speaking, identify modern capitalism as having emerged in the cities of Amsterdam, London and Antwerp right around the time the tulip mania took hold.

The Introduction of Tulips in the Dutch Republic

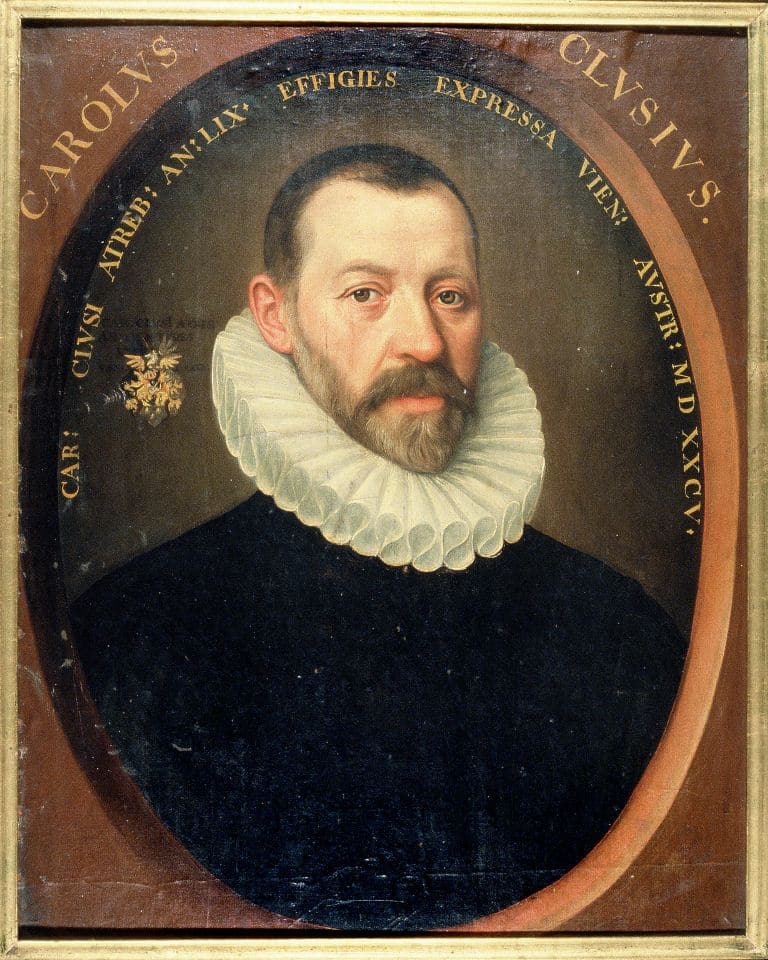

Tulips were introduced into the United Provinces of the Dutch Republic around 1593 by the French-born botanist Carolus Clusius, the leading scientific horticulturist of the late sixteenth century, who had taken up a position at the University of Leiden.

Clusius first determined that this bulb from Central Asia could grow quite well in the relatively temperate climate of Northern Europe. And soon, they became popular amongst the upper and middle classes, who developed an affinity for decorating their homes with them as Dutch society entered a period of increasing prosperity in the early seventeenth century.

Tulips come in many different colors and can be multi-colored also. Moreover, they are highly cultivatable, and different colors and hues can be produced by those who know how to do so, although this process can take years to achieve.

Thus, as tulips became increasingly fashionable, there was increasing competition amongst the Dutch upper class to have the most unique and unusual tulips in their homes.

As this occurred, the price of tulip bulbs began to increase, and this was only compounded when merchants and growers also began to fork out ever-larger sums of money for bulbs of a certain quality.

The Bubble Reaches Its Peak

This might have just remained an inflated market, but in the mid-1630s, it turned into the world’s first massive economic bubble as speculation on the more prized bubbles became truly enormous.

This was driven not just by the Dutch but also by merchants and financiers in France and other adjoining regions now speculating on the tulip market in Holland and the other Dutch provinces.

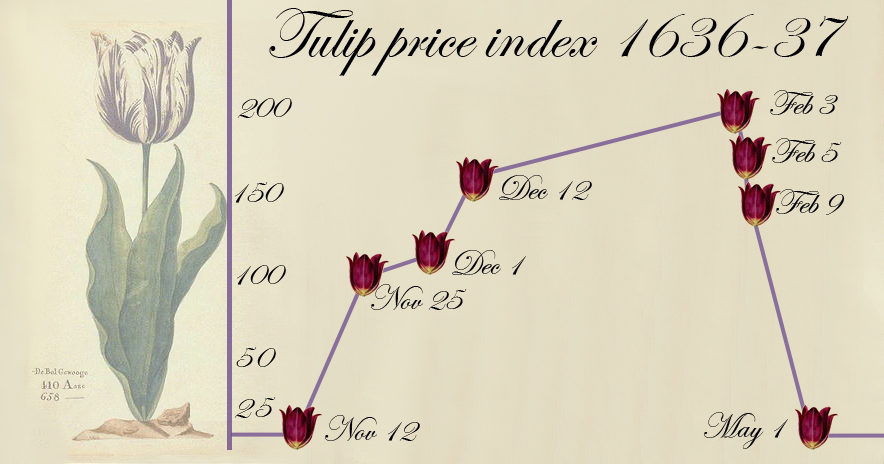

As they did, the price of the more exotic bulbs began to rise sharply in 1634. There was already a bubble at this stage, but it ballooned in 1636 as the more coveted bulbs, such as the Switzer, rose over 1000% in price in just two months between December 1636 and February 1637.

By this time, contracts for tulip bulbs were sometimes being sold over and back multiple times per day, with traders making a handsome profit in the space of just a few hours, much like cryptocurrency investors today are often able to make a large profit in the space of just a few days if they can come out on top of a wave of particular volatility in the cryptocurrency markets.

The Tulip Buble Pops

In the spring of 1637, some tulip bulbs were being traded for the same amount of money that one would spend on a sizeable house in Amsterdam.

Of course, it couldn’t last. Economic bubbles never do. In the mid-spring of that year, the price of tulip bulbs began collapsing as an outbreak of the bubonic plague in Haarlem suddenly saw traders avoid auctions. The speculative bubble began to deflate rapidly across the Republic as they did.

By the summer of 1637, many who had a large stake in the market when it began to collapse had lost fortunes, and the Republic’s merchant community was picking through the wreckage of the world’s first economic bubble.

There are many reasons why the tulip mania or fever developed, but they are all intimately connected with the developing economic landscape of the Dutch Republic at the time.

The Amsterdam Stock Exchange had opened in 1602, and it was here that many of the contracts on tulip bulbs were traded in the mid-1630s.

In addition, Amsterdam, Antwerp, and London merchants began using innovative financial instruments in the second half of the sixteenth century. By the 1630s, these were developed enough to deal in large-scale speculation on something as ephemeral as tulip bulbs.

Thus, it is perhaps unsurprising that the world’s first major economic bubble would develop in a place like the Dutch Republic at this time, for it was here that modern capitalism was emerging, with all its paradoxical capacity for societal progress and financial lunacy.