Hidden for centuries by a thick layer of jungle, ancient Mayan cities are finally being rediscovered thanks to new technologies and the tireless work of archeologists.

Ocomtún is one of the most recent discoveries. It was unearthed in 2023 by the Slovenian archaeologist Ivan Šprajc and his team.

This ancient Mayan city in the Yucatan was occupied for centuries, peaking around the year 700. The city was home to as many as 40,000 people at one time.

So, how did this team of archaeologists locate these ancient ruins deep in a nearly impenetrable jungle? They mapped out promising areas by sending billions of laser pulses down from planes, then used those maps as a guide as they fought their way through miles of untouched jungle.

LiDAR imaging is unveiling new cities all over the world.

Read on to learn more about ancient Mayan cities and the modern technology that’s making it possible for archeologists to bring these significant historical sites back into the light of day.

The Ancient Maya

The Ancient Mayan civilization dominated what is now southern Mexico as well as parts of Guatemala, El Salvador, Belize, and Honduras.

This civilization began over four thousand years ago, rose to prominence around 250 BC, and has endured to the present day. It declined but never really disappeared. Today, dozens of Mayan languages are still spoken by six million people.

The first Mayan cities were constructed around 750 BC. By 500 BC, they began to build monumental temples – the step pyramids that are such a fundamental symbol of Mayan culture.

Some of these pyramids are over two hundred feet tall. Stripped back to their gray interiors over the centuries, these pyramids were once covered in stucco and painted with murals in bright colors: red, yellow, blue, and green.

A recent estimate tells us that there were around eleven million Mayans at the height of their civilization. But as LiDAR mapping continues to uncover previously undiscovered cities, that number continues to rise.

This vast civilization was one of the most advanced in all of the Americas. They developed a complex writing system and possessed extensive knowledge of both astronomy and architecture. The Mayan civilization was one of the first in the world to develop the concept of zero, and their numeral system made it possible for them to record very large numbers.

Like other empires, Mayan rule in early centuries revolved around the concept that their kings were divinely appointed, with the ability to intercede between humans and the gods. These kings ruled over a vast network of city-states.

The Maya were not a single unified people. These city-states often warred amongst each other and competed for power in the region, and kings proved their worth in battle.

As the aristocracy multiplied and consolidated their power, the power of Mayan kings diminished. In later centuries, many city-states were ruled by a council of nobles.

Mayan cities usually centered around a few culturally significant structures: pyramid temples, palaces, ballcourts, and buildings designed to observe the stars. The largest cities were home to as many as 120,000 people.

Trade flourished throughout the region. Mayan traders traveled as far as the ancient city of Teotihuacan, located in what is now central Mexico. They produced large quantities of cotton and traded in textiles as well as gold, turquoise, and obsidian. Major cities along the coastline traded in salt.

The Mesoamerican slave trade was also an important part of both Mayan trade networks and the wider Mesoamerican culture.

Commoners captured in battle were traded or used as laborers, while captives of high status were often tortured and killed in religious ceremonies. Major events such as the ascension of a new ruler or the dedication of a new building were marked with human sacrifice.

Dated monuments indicate that the Mayan culture peaked around the eighth century AD. After that, the population began to decline.

In the centuries leading up to the year 1000, dozens of the stone cities that the Mayan people had built and inhabited for generations were abandoned as the population shifted towards the northern Yucatan.

The exact sequence of events that led to this is unknown. Archaeologists believe that this decline can be attributed to a combination of factors, including prolonged drought and foreign invasion, most likely by the Toltecs. Overpopulation and soil depletion may have also played a role.

One of the most interesting things about this new discovery is that Ocomtún appears to have been inhabited for centuries after other cities in the area were abandoned.

The Ocomtún Expedition and LiDAR Technology

The prolific archaeologist Ivan Šprajc led this expedition, which was a partnership between the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts and Mexico’s National Institute for Anthropology and History.

The ruins of Ocomtún are located in the center of the Yucatan peninsula, in a nature preserve called the Balamkú Ecological Conservation Zone. The team of archaeologists who discovered these ruins had to fight their way through sixty kilometers of dense jungle in order to reach the site.

But how did they know where to look to begin with?

Šprajc and his team used LiDAR technology to search for undiscovered ruins hidden beneath centuries of overgrowth.

They begin by scoping out potential sites by using satellite images to search for artificial shapes beneath the greenery, circles and squares and rectangles that might indicate hidden ruins. Then they moved on to LiDAR imaging.

The term LiDAR stands for “light detection and ranging.” In order to collect images of potential archeological sites, a plane equipped with LiDAR equipment flies over the area and sends down billions of laser points to create images.

It took three four-hour flights to scan Ocomtún, each one costing thousands of dollars.

LiDAR sensors measure the time it takes for each laser pulse to return and use that information to create a three-dimensional map of the area.

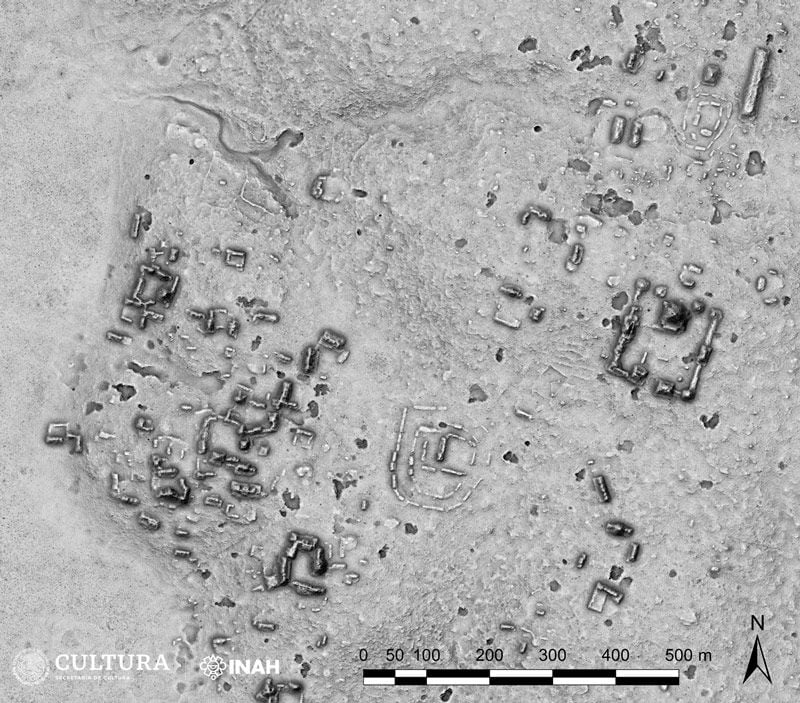

The image created with LiDAR technology provides a clear map of the ancient ruins; pyramids and walls are easily visible against the surrounding landscape.

It provides adventurous archeologists like Šprajc with a route through the jungle, though of course the team still has to cut a new path themselves.

The ruins were over thirty miles from the nearest road. Wielding chainsaws and macetes, Šprajc and his team worked for two weeks to clear a path through the dense undergrowth.

The Lost City of Ocomtún

The name Ocomtún comes from the Mayan word for ‘stone column’. It takes its name from the many stone cylinders that the team found at the site.

Built on high ground surrounded by marshy wetlands, this massive Mayan metropolis covered over 50 hectares of land.

Some of the structures are so large that archeologists estimate hundreds of laborers must have worked for decades to quarry and transport the stone required for construction.

Fragments of stone all around the city indicate a dense suburban area, which tells us that Ocomtún was an important cultural center and trade hub.

While the most significant surviving structures of this site appear to have been constructed between 600 and 900 CE, there is evidence that the site was inhabited beginning in 1000 BC, making this one of the area’s first population centers. Archeologists have found shards of pottery dating from over three thousand years ago.

There are also signs that this site was inhabited long after other Mayan cities were abandoned.

Šprajc and his team found irregular mounds on top of older structures. These mounds contained figurines characteristic of what Mayans were creating in later centuries, indicating that this site may have still been inhabited as late as the Spanish conquest.

Given that most major cities in this area were abandoned by the year 1000 as Mayan peoples relocated to population centers near permanent sources of fresh water, the occupation of this site for centuries after this population shift would be a major archaeological discovery. Investigation into the details of this possibility is ongoing.

Archeologists are finding more clues as they continue to excavate the site, including a rich abundance of hieroglyphic texts carved into the stone of Ocomtún itself. Continued research is uncovering advanced hydraulic works and complex agricultural systems, giving insight into how these population centers thrived for as long as they did.

Ongoing Research

Densely overgrown and relatively dry, the region that Šprajc is exploring was once regarded as a sort of black hole for the Mayan civilization.

The streams in this region dry up every summer, and the water stored beneath the ground is trapped under thick layers of limestone.

Until recently, archaeologists assumed that ancient peoples weren’t able to survive here, much less thrive in the way that the acropolis of Ocomtún evidently did. How they were able to live so long and so well in the region remains a mystery.

There are more promising sites in the area yet to be explored, more ancient cities yet to be discovered. With additional funding and permission from the Mexican government, teams of archaeologists will continue to unearth the mysteries of the Maya.