Last updated on September 29th, 2022 at 03:22 pm

Perhaps the most peculiar aspects of Christianity today are the divisions within it. For instance, hundreds of different branches of Protestantism originated from the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century.

But few would dispute that Lutheranism, Calvinism, Presbyterianism, Anabaptism, or one of the other major branches of Protestantism effectively share the same origins as Roman Catholicism.

The same, however, cannot be said of Greek Orthodox Christianity, which is very distinctive from western forms of Christianity, almost as though the two religions do not stem from the followers of Christ in the late antique world.

How did the Roman Catholic and the Greek Orthodox Church become so divided?

The Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox Churches

To understand how the Roman Catholic Church and the Greek Orthodox Church split in the Great Schism of 1054, one needs to look back into the world of late antiquity. While the Roman Empire was collapsing, the Christian faith gradually spread across the Levant, North Africa, and all of the Roman parts of Europe.

This period was a time of great success for Christianity, as it replaced the polytheistic religions of Rome and Greece in the Mediterranean world. Still, it was also a time of debate and controversy among Christians.

In the fourth century leading figures within the Christian church were divided on several issues.

One of the most prominent of these was the nature of the Trinity of God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit.

In the fourth and fifth centuries, divisions arose about the nature of the Holy Spirit, with those who were leading religious figures within the Eastern Roman Empire contending that the Holy Spirit was created by God alone, but church fathers in Rome and parts of Western Europe holding that the Holy Spirit proceeded from both God and Jesus.

Additional issues concerned the use of icons or religious images, which the Greek Church favored more than the Roman Church, but which Christian theologians noted had been strictly prohibited by God in the Ten Commandments he gave unto Moses.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the two churches were already divided by the fifth century over the issue of who was the leader of the Christian faith on earth.

Church Leaders Helped Lead to the Great Schism

In the western Roman Catholic Church, it was argued that the Bishop of Rome, a figure who would subsequently become known as the Pope, was the anointed leader of the Church.

Those who held that this was the case argued that Jesus had named the Apostle Peter as his successor, and Peter had subsequently become the first Bishop of Rome.

Therefore Peter’s successors in that position were the de-facto leaders of all Christians.

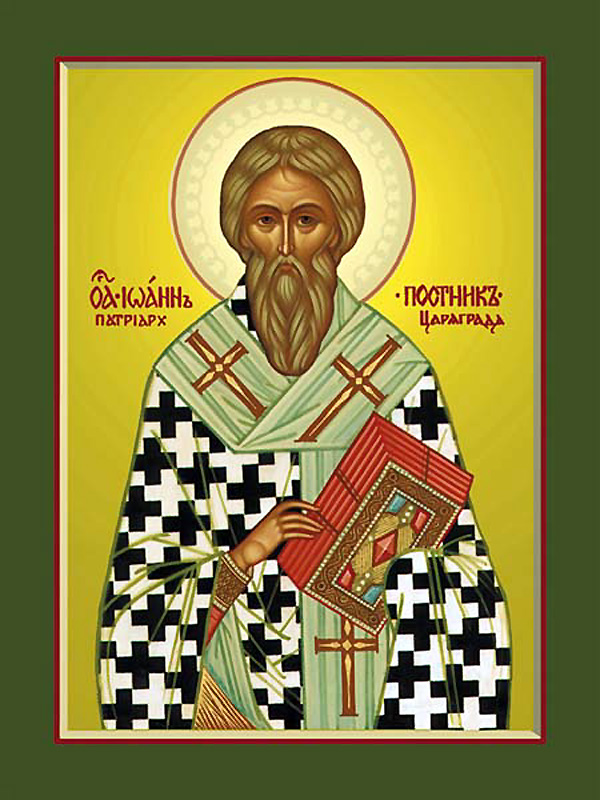

However, to the east many believed that the Bishop of Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire where Istanbul stands today, a figure who would become known as the Patriarch of the Greek Orthodox Church, was the supreme leader of the followers of Christ on earth.

This was because the first Roman emperor to adopt Christianity as the state religion, Constantine, had built the city of Constantinople and made it the center of political and religious power in the empire.

Thus, at the heart of the division between what became the Roman Catholic Church and the Greek Orthodox Church was a power struggle between the Bishop of Rome or Pope and the Bishop of Constantinople or Patriarch. Some cultural divisions further augmented this. For instance, Latin became the language of the Roman Catholic Church, while Greek was the tongue and written word of the Greek Orthodox Church.

Theological Disputes in the Early Middle Ages

These divisions between Christianity’s western and eastern branches continued for hundreds of years, often with significant bouts of unrest.

For instance, in the seventh century, further points of contention arose around the use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist. Given these ongoing disputes between Rome and Constantinople, it is unsurprising that both churches were rivals in converting Pagan peoples elsewhere in Europe during the Early Middle Ages.

Rome focused on regions such as Britain, Germany, Denmark, and western Poland.

At the same time, Constantinople was primarily concerned with extending the Greek Orthodox Church across the Balkans and into Ukraine and later Russia.

However, despite this keen rivalry and the many disputes between the western and eastern churches, they maintained relations and communication throughout the Early Middle Ages. That all changed with the Great Schism of 1054.

The Great Schism of 1054

On the surface, the Great Schism of 1054 was hardly a new departure from what had gone before. It was effectively caused by the many points of difference in theological interpretation and religious practice between the Roman and Greek churches for centuries.

However, these came to a head in the mid-eleventh century. The flash point occurred in southern Italy, where Norman knights from northern France had been campaigning to carve out a new kingdom in the south of the peninsula.

These displaced the Greek Byzantine Empire ruled from Constantinople from its possessions in southern Italy in the 1040s and early 1050s.

Then Pope Leo IX began forcing churches in southern Italy that had practiced Greek Orthodox Christianity to start conforming to the Latin rites of the Roman Catholic Church.

This deeply angered the Patriarch of the eastern church in Constantinople, Michael I. Diplomatic efforts followed. Still, when an embassy that Pope Leo sent to Constantinople in 1054 demanded that the Patriarch acknowledge the supremacy of the Pope over the Christian churches, this was refused, and diplomatic relations ended.

The eastern church excommunicated the Pope, and the western church excommunicated the Patriarch.

At the time, it was not fully appreciated how significant this sundering of relations or ‘schism’ was, but as the decades and then centuries went by and communication and cooperation between the Roman Catholic Church and the Greek Orthodox Church were not restored, people began to refer to these events of 1054 as ‘the Great Schism.’

Attempts at Reconciliation

Many efforts in the years followed to end the Great Schism. For instance, in 1272, a major conference was convened in the city of Lyon in southern France with that specific goal in mind.

The western and eastern churches were anxious to have greater cooperation established to confront the threat of Muslim expansion in the Levant and Turkey with their combined religious and political strength.

The Byzantine Empire was particularly anxious to ensure this as it was the target of Muslim expansion. Moreover, its empire in the Eastern Mediterranean underwent a pronounced decline.

Effectively it needed help from Rome, and it claimed that it was willing to make concessions on theological matters to acquire it.

Yet the Council of Lyon failed to end the Great Schism, and it continued into the fourteenth century. By the early fifteenth century, the situation was desperate.

A new power, the Ottoman Turks, were conquering what was left of the Byzantine Empire in Greece and western Turkey.

Eventually, the Byzantines, and the Patriarch of the Greek Orthodox Church, were hemmed into the city of Constantinople.

Thus, a final effort at reconciliation was attempted in 1439 when representatives from both churches convened at a council in the city of Florence in Italy.

It failed to achieve a rapprochement, and in 1453 Constantinople fell to the Ottomans, bringing an end to the Byzantine Empire.

The great cathedral of Hagia Sophia in the city, the spiritual home of the Patriarchs, was converted into a mosque.

The Greek Orthodox Church would live on and find a new political home in cities like Kyiv and Moscow, but so too would the Great Schism, which never ended and continues to this day.