In speculative fiction, H.P. Lovecraft’s name elicits fanaticism second only to Edgar Allan Poe and Bram Stoker. But not for surpassing the bar set by these undisputed giants of the dark and macabre but for the sub-genre he carved out for himself.

Credited with creating “cosmic” horror, Lovecraft shifted the genre from stories that reflect a clear moral code (based primarily on Western values) to a genre intended to disturb, provoke, and horrify the reader.

And rather than present his tales in an elegant, refined writing style typical to the horror genre, Lovecraft wrote in a comparatively awkward, contrived language resulting in a style often described as factual reportage—rather than fictional storytelling.

Although Lovecraft’s writing is, for many, an acquired taste, he is nonetheless one of the most revered writers of the horror genre in literary history. And it is no surprise to his millions of fans that his works outsell those of Poe and Stoker combined.

A Tragic Life Begins

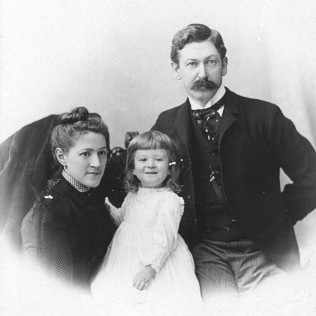

Howard Phillips (“H.P.”) Lovecraft was born on August 20, 1890, in Providence, Rhode Island, to Winfield Scott and Sarah Susan Lovecraft, and began life in his mother’s family home with his parents, maternal aunts Lillian and Annie, and maternal grandparents, Whipple and Robie.

When Howard was just two and a half years of age, his father suffered a psychotic breakdown and was hospitalized.

When it was discovered that Winfield had been behaving and talking strangely for a year or more, he was formally institutionalized.

Because Sarah’s family was financially secure and Winfield had been a successful businessman, they could afford to admit him to Butler Hospital, a private psychiatric facility in Providence.

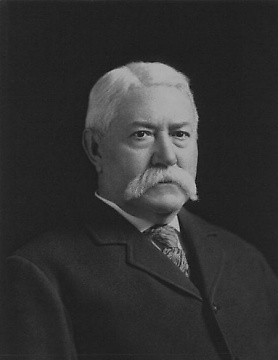

Howard’s grandfather Whipple stepped in to fill the void in Winfield’s absence. Howard would later say that his grandfather became the center of his universe.

As a result of his grandfather’s attention, Howard became efficient at reading and writing by age three, and for a time, it seemed his life would stabilize. But then, in 1896, when Howard was just five and a half, his grandmother Robie died.

While nothing suggests that Howard was particularly close to his grandmother, he would later comment that her death set his family “into a gloom from which it never fully recovered.”

Moreover, the black mourning dresses his mother and aunts wore terrified him. They ignited nightmares that would plague him for the rest of his life, yet ironically, become a significant characteristic in his writing.

Two years later, as his life began to settle, darkness struck again. His father, Winfield, died from the primary cause of his mental illness: syphilis.

After this horrific event, his mother turned all her attention to Howard, doting and pampering the boy, rarely letting him out of her sight. His grandfather provided his only means of escape.

Early Inspiration

Whipple encouraged Howard to appreciate literature, particularly the classics and English poetry. But he also orally presented the impressionable boy with “weird tales” he fashioned in the manner of Gothic novelists like Ann Radcliffe and Matthew Lewis.

During this period, Howard was first introduced to the stories he would later credit as inspiring his writing, such as “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, One Thousand and One Nights, a collection of Middle-Eastern folktales, Thomas Bulfinch’s collection of myth and legend Age of Fable, and Ovid’s “Metamorphoses.”

During this period, his nightmares were also invaded by beings he referred to as “night-gaunts,” creatures that would appear in his writing some thirty years later.

First Works

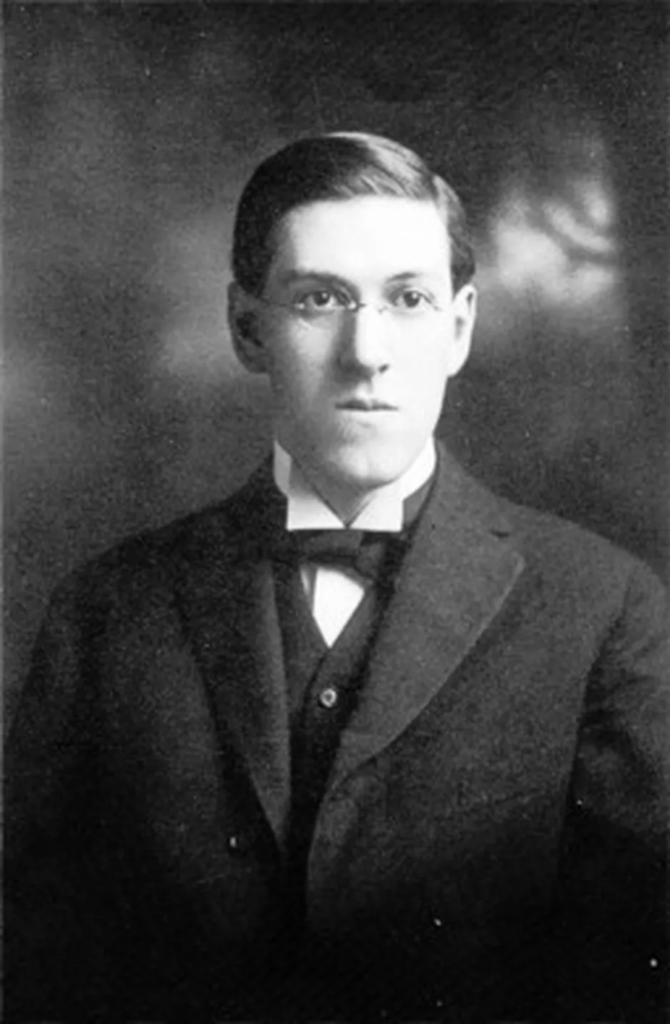

At seven, Howard experienced what can best be described as a spiritual epiphany. Having immersed himself in Greek and Roman mythology, the Greco-Roman pantheon of gods supplanted his Christian ideals, prompting his first known work, a re-telling of Homer’s “Odyssey.”

The following year his interests turned to astronomy, writing several papers on the subject and publishing his own periodical, Rhode Island Journal of Astronomy.

Due to his fragile state of mind, Howard was permitted to choose between public school and private tutors—but spent most of those years solely pursuing his own interests.

But then his grandfather’s business holdings turned downward, the family fortune dwindled, and everything disintegrated.

By the spring of 1904, the last of the Lovecraft fortune ran out, making the estate’s upkeep untenable. That fall, Whipple died, forcing Sarah to move into a small duplex with her son.

Devastated by the loss of his grandfather, Howard fell into one of the darkest periods of his life and even considered suicide. He began suffering “near nervous breakdowns” and other undetermined malaise that would plague him for the rest of his life.

In a letter referring to this time, he said, “I was and am prey to intense headaches, insomnia, and general nervous weakness which prevents my continuous application to any thing.”

A short time later, Howard decided to attend high school—but never attended for any length of time. Discovering an interest in chemistry and physics, he resumed publication of his Rhode Island Journal of Astronomy, focusing more on hard science.

During this period, he created two fictional works he would later be known for: “The Beast in the Cave” and “The Alchemist.”

In 1908, just before his high school graduation, he maintained that he planned to attend Brown University. In fact, Howard never attended school again.

Finding Recognition

Howard’s first non-self-published work appeared in a local newspaper in 1912, a poem called “Providence in 2000 A.D.”

Providing the first inkling of what critics today consider his underlying racism, the piece’s premise is an imagined future where Americans of English descent are displaced by Irish, Italian, Portuguese, and Jewish immigrants.

When Howard was 21, “Letters to Editor” he’d written began appearing in pulp and weird-fiction magazines, most notably Argosy.

In 1913 he penned a scathing letter criticizing author/screenwriter Fred Jackson, one of Argosy’s most prominent writers, taking a stance that would effectively define him as a writer.

Howard described Jackson’s stories as “trivial, effeminate, and, in places, coarse,” further arguing that his characters exhibit the “delicate passions and emotions proper to negroes and anthropoid apes.”

This harsh criticism sparked a letter-writing feud between the two writers (and their respective supporters) that lasted almost a year.

The ultimate effect of this clash was recognition from United Amateur Press Association (UAPA) chief editor, Edward F. Daas, who invited both Lovecraft and Jackson to join the organization; which Howard accepted in April of 1914. Lovecraft would use this recognition to make himself and his views more widely known.

Advocate for Amateurism’s Superiority to Commercialism

For the next decade, Lovecraft focused on amateur journalism, advocating amateurism’s superiority over commercialism, whose publications he defined as low-brow and paid little.

He believed that amateur journalism represents a legitimate professional career (much like Internet bloggers in modern times).

In late 1914, Lovecraft was appointed chairman of the Department of Public Criticism of the UAPA. From this position, he advocated for the superiority of archaic English language usage, openly criticizing other UAPA contributors who used “Americanisms” and common slang.

His highly-vocal position was that immigrants were bastardizing the “national language” and that British English was far superior to American English.

Becoming a Bonafide Writer

In 1916 at the age of 26, Lovecraft published his first short story, “The Alchemist,” in the main UAPA journal.

At the urging of writer/publisher W. Paul Cook, another UAPA member, Lovecraft began writing more prose fiction.

Soon after, he wrote “The Tomb” (by his own admission, based on Poe’s work) and “Dagon” (considered Lovecraft’s first work displaying the concepts and themes that make his writing unique).

In 1919 he published “Beyond the Wall of Sleep,” his first delve into science fiction.

At the age of 29, despite his mother having been admitted to Butler Hospital after suffering a nervous breakdown, Lovecraft became more outgoing, forging friendships with many renowned writers, including writer/dramatist Lord Dunsany (The King of Elfland’s Daughter), and horror/sci-fi writer Frank Belknap Long (The Hounds of Tindalos).

Lovecraft began pumping out material including, “The White Ship” and “The Doom That Came to Sarnath” (part of Lovecraft’s so-called “Dream Cycle” stories), and “The Cats of Ulthar” and “Celephaïs” (two works clearly ala Dunsany).

Late in 1920, Lovecraft began work on the so-called “Cthulhu Mythos” stories, a fictionalized mythology fans today consider the work that sets him apart from other horror genre writers.

The name “Cthulhu” derives from the central creature in his short story, “The Call of Cthulhu,” published in Weird Tales in 1928. “The Nameless City” is the first story that falls squarely within the Cthulhu Mythos.

Tragedy, Marriage, Disappointment

On May 24, 1921, Sarah Lovecraft passed away in Butler Hospital from complications stemming from a gallbladder operation.

Although the initial shock sent Howard into a deep depression, and he again contemplated suicide, he consoled himself by attending amateur journalist conventions.

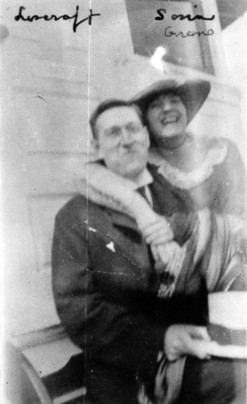

At one such convention, he met his future wife, Sonia Green, a divorcee. Despite disapproval from his aunts, Howard and Sonia married on March 3, 1924. The groom moved into his bride’s Brooklyn, New York apartment.

Shortly after marriage, Sonia lost her business, and her bank failed—dissolving her assets. Howard attempted to find work to support his wife, but his lack of experience made him virtually unemployable.

Encouraged by a group of New York writers and poets who’d befriended him, Lovecraft submitted several short stories to Weird Tales, which subsequently published several of them, including, “Under the Pyramids,” which eased the couple’s financial burden.

In early 1925, Sonia gave up her New York apartment and moved to Cleveland following a job opportunity, forcing Howard to move into a small, seedy apartment on his own. After several years apart, Howard and Sonia divorced and went their separate ways.

Soon after, Edwin Baird, editor of Weird Tales, offered Lovecraft a job as an editor, which he declined, unwilling to relocate to Chicago, the magazine’s home base.

Farnsworth Wright filled this position, the man Lovecraft had so harshly criticized. As no surprise, most of Lovecraft’s subsequent submissions were rejected.

In August of 1925, Lovecraft penned “The Horror at Red Hook” and “He,” in which the narrator states, “My coming to New York had been a mistake; for whereas I had looked for poignant wonder and inspiration . . . I had found instead only a sense of horror and oppression which threatened to master, paralyze, and annihilate me.” Amid this despair, he developed the outline for “The Call of Cthulhu” and “Supernatural Horror in Literature.”

Howard could not support himself despite a steady income, so he moved back to Providence to live with his aunts.

Return to Providence

The period following his return to Providence represents the most creatively prolific time in Lovecraft’s career, penning some of his most memorable works, including, “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath,” “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward,” “The Call of Cthulhu,” and “The Shadow Over Innsmouth.”

Capitalizing on his recognition, Lovecraft was hired-out as a ghostwriter, penning “The Mound” (for short-story writer Zealia Bishop), “Winged Death” and “The Diary of Alonzo Typer,” and revised work for other authors.

During this time, he made the acquaintance of famed escape artist Harry Houdini, who attempted to help Lovecraft by introducing him to the head of a newspaper syndicate. Any subsequent plans, however, were cut short when Houdini perished in 1926.

Beginning of the End

In 1931 Lovecraft completed his novella, At the Mountains of Madness, and submitted it to Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright—who promptly rejected it. Lovecraft took the rejection badly and set the story aside.

In 1935 after signing with literary agent Julius Schwartz, Astounding Stories editor F. Orlin Tremaine accepted the novella, serializing it in the February, March, and April 1936 issues, paying Lovecraft $315 (the most he’d ever received for a single piece).

However, the story was carelessly edited, with spelling, punctuation, and formatting alterations, and several pertinent passages were completely omitted. Outraged, Lovecraft called Tremaine “that god-damned dung of an hyaena.”

In late 1936, The Shadow Over Innsmouth was published as a paperback and promoted in Weird Tales and other fan magazines. But as Lovecraft would discover, this book was also poorly edited–bringing scorn from readers questioning his basic writing ability. Though 400 copies were printed, only 200 were sold, and the rest were destroyed.

At this point in his life, Lovecraft felt he could go no further as a writer. Shortly after penning “The Haunter of the Dark,” he stated that the hostile ill-handling of At the Mountains of Madness had “done more than anything to end my effective fictional career.”

From then on, Lovecraft’s deteriorating psychological and physical states made writing impossible.

Howard Phillips (“H.P.”) Lovecraft passed away on March 15, 1937, of small intestine cancer.

A Legacy Like No Other

Shorty after Lovecraft died, the so-called “Lovecraft Circle” (an odd cadre of writers, editors, and artists that included anthropologist/writer August Derleth) founded Arkham House, a publishing company specializing in weird fiction, intent on keeping Lovecraft’s works in print.

Since relatively few readers knew of Lovecraft in his lifetime, fans today owe their knowledge of him to this mutual-admiration society.

In subsequent years, Arkham House was responsible for the spawning interest in Lovecraft’s work in many other arenas:

Regarding scholarly works, the so-called “Lovecraft Studies” of the 1970s sought to establish H.P. Lovecraft as a significant author in the American literary canon.

In music, in the 1960s, the Psychedelic Rock band H. P. Lovecraft released two albums based on his story themes, and in 1970 the Heavy Metal band Black Sabbath released their debut album, Black Sabbath, which listed the track “Behind the Wall of Sleep,” referencing Lovecraft’s story of the same name.

In philosophy, the Speculative Realist Philosophical Movement of this century was founded on the premise that Lovecraft was a “productionist” writer who was uniquely obsessed with gaps in human knowledge.

In mainstream publishing, Lovecraft’s works have been published by several different series of literary classics, including Penguin Classics, The Library of America, and Barnes & Noble.

In the world of gaming, Lovecraft’s writing inspired Chaosium’s tabletop role-playing games, “Call of Cthulhu,” “Arkham Horror,” and “Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth.”

Sources

“Biography of H. P. Lovecraft, American Writer, Father of Modern Horror,” https://www.thoughtco.com/biography-of-h-p-lovecraft-american-writer-4800728

“Providence in 2000A.D.,” by Howard Philips Lovecraft: http://www.wyrmis.com/blots/2015/13/blot60940-providence-2000.htmlProvidence in 2000 A.D.”

Providence 2000 A.D.”

Britannica, “Lovecraft,” H.P. Lovecraft | Biography, Books, & Facts | Britannica

Study.com., “H.P. Lovecraft: Books and Monsters,” HP Lovecraft: Books & Monsters | Study.com

H.P. Lovecraft, “Notes on Writing Weird Fiction,” https://www.letras.cabaladada.org/letras/notes_writing_weird_fiction.pdf

“H.P. Lovecraft, His Life,” https://www.hplovecraft.com/life/