In June of 1970, journalist Hunter S. Thompson was sent to his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, to cover the highlights of the world-famous Kentucky Derby, for Scanlan’s Monthly. The result was a now infamous article entitled, “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved.”

Virtually ignoring the race itself, Thompson focused instead on the orgy-like atmosphere– “thousands of people fainting, crying, copulating, trampling each other and fighting with broken whiskey bottles”– surrounding the event.

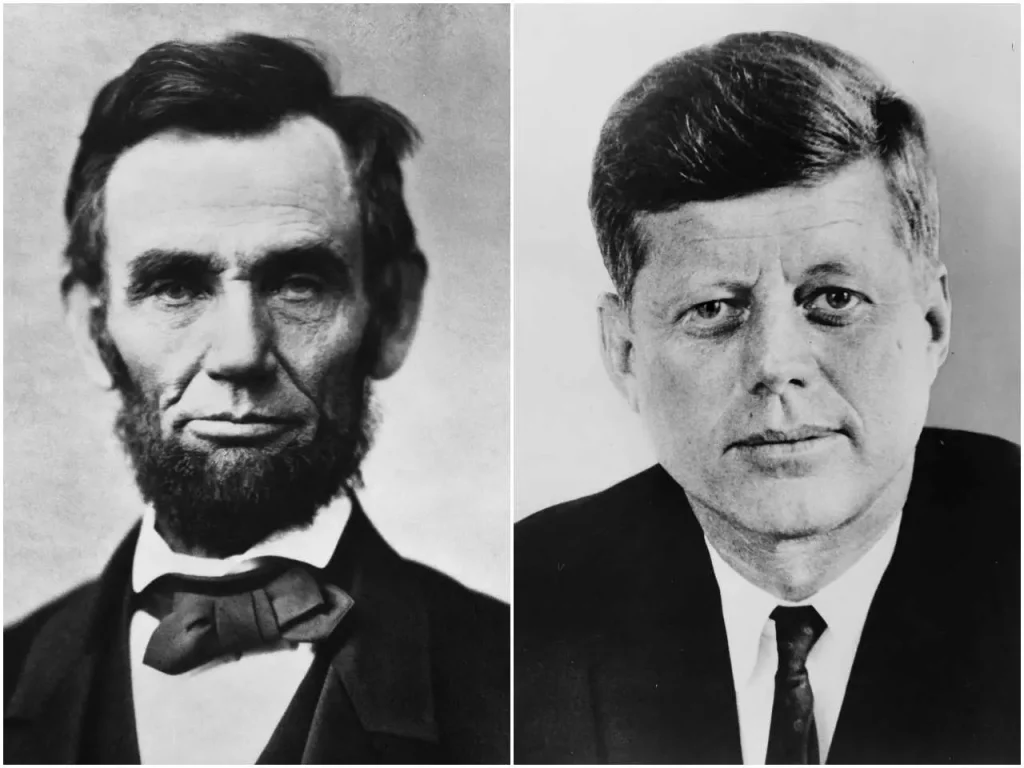

Writing in “first person,” Thompson set the carnage against the backdrop of the current American political scene: President Richard Nixon had ordered the bombing of Cambodia, and four students had been killed by Ohio National Guardsmen at Kent State University just two days later.

Though blatantly disregarding the task assigned (and running up an exorbitant liquor and food bill at his hotel), “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved” is considered one of the most significant sports articles of the 1970’s, and more importantly, marked the birth of what has become known as “gonzo journalism” (a style of reporting in first person, making no claims of objectivity, the reporter being part of the story).

While this article doesn’t define Thompson–or even represent his impressive body of work–it marks a turning point (perhaps, breaking point) for one of the most brilliant, prolific, original, and fearless writers of the past century.

Early Life

Hunter Stockton Thompson was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on July 18, 1937, the first of three sons born to Jack Robert Thompson (an insurance adjuster) and Virginia Davison Ray (head librarian at the Louisville Free Public Library).

In December of 1943, when Thompson was six years old, his family moved to the historic neighborhood of Cherokee Triangle in the upscale area of The Highlands, in Louisville; becoming neighbors of future mystery novelist, Sue Grafton.

Though from an early age Thompson displayed natural athletic abilities, his disdain for authority–even as a boy—deterred any aspirations of participating in organized sports. Turning his attention instead to the written word, Thompson became an avid reader, soon discovering the early works of counter-culture icon Jack Keuroac, and later, J.P. Donleavy.

On July 3, 1952, when Thompson was 14, his father died of myasthenia gravis (a neuromuscular disease) at just 58 years of age. From that time on, Thompson and his brothers were raised solely by their mother, Virginia, living on her librarian’s salary.

Soon after her husband’s death, Virginia began drinking heavily.

Education

At about six years of age, Thompson attended I.N. Bloom Elementary School where, despite his dislike for authority, co-founded the Hawks Athletic Club (and by some accounts, sometimes participated). This led to an invitation to join Louisville’s Castlewood Athletic Club, an organization that prepared young boys for high school sports. (Thompson, of course, didn’t accept.)

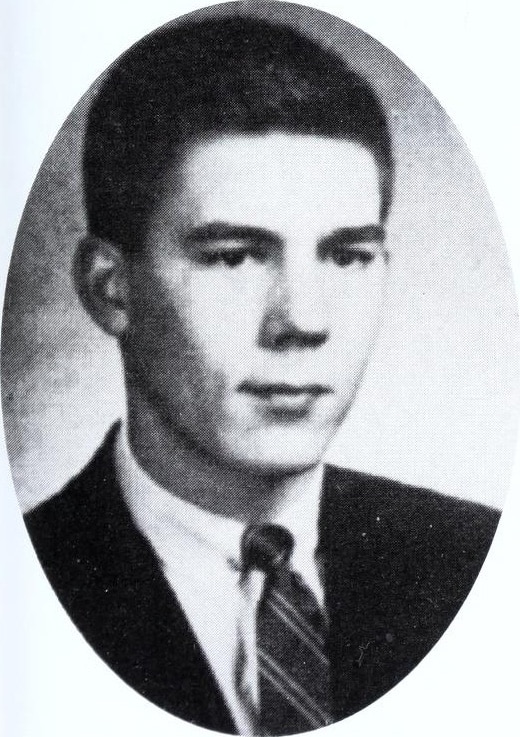

In 1951, Thompson temporarily attended Atherton High School, before transferring in the fall of 1952 to Louisville Male High School. That same year, he was admitted to the prestigious Athenaeum Literary Association, a school-sponsored literary social club founded 1862. (Its members—all from Louisville’s upper-crust–included Porter Bibb, future publisher of Rolling Stone magazine.)

As an Athenaeum member, Thompson contributed articles and worked on the club’s yearbook, The Spectator;until 1955, when he was summarily ejected for criminal activity. Having been in the car driven my the perpetrator, Thompson was charged as an accessory to robbery and sentenced to 60 days in Kentucky’s Jefferson County Jail.

Released after serving 31 days, Thompson was barred from taking final exams, preventing his graduation.

Military Service

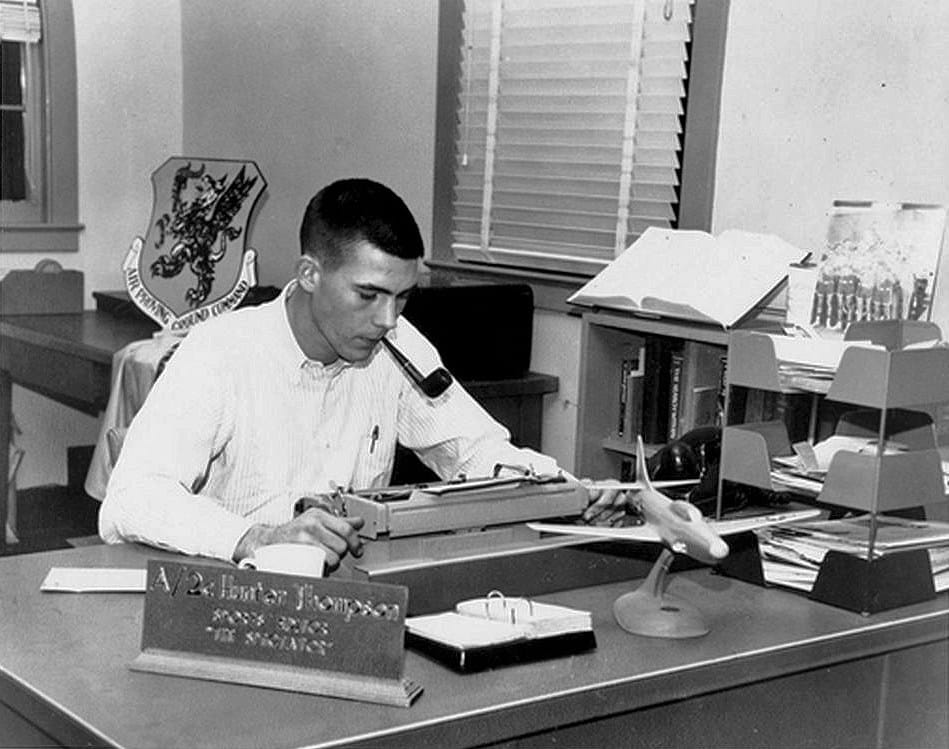

In reaction to the punishment received from Louisville Male High School, Thompson did the unexpected: he enlisted in the United States Air Force.

Once completing basic training at Lackland Air Force Base, in San Antonio, Texas, Thompson was transferred to Scott Air Force Base, in Belleville, Illinois, where he studied electronics. (He applied to flight school, but was rejected.)

In 1956, Thompson was transferred to Eglin Air Force Base, near Fort Walton Beach, Florida, where he took night classes at Florida State University. Subsequently landing his first professional writing job, Thompson was made sports editor of Eglin’s, Command Courier (a job he ultimately got by lying about his job experience). As editor, Thompson traveled the US with the Eglin Eagles football team, reporting on their games.

In 1957, Thompson began writing a sports column for The Playground News, a local newspaper published in Fort Walton Beach, Florida; but received no byline as Air Force regulations forbade outside employment.

By 1958, Thompson’s natural contempt for authority paid off when his commanding officer recommended him for an early honorable discharge, stating, “Airman First Class Thompson, although talented, will not be guided by policy. Sometimes his rebel and superior attitude seems to rub off on other airmen staff members.”

Early Career

By the end of 1958, Thompson was working as sports editor for a small newspaper in Jersey Shore, Pennsylvania, before relocating to New York City.

There he audited courses at the Columbia University School of General Studies, during which time he worked as a copy boy at Time for $51 a week. (While employed at Time, Thompson typed out sections of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms in order to learn their writing styles.) After a year, Time fired him for insubordination.

Hired and fired as a reporter for The Middletown Daily Record in Middletown, New York, in 1960, Thompson moved to San Juan, Puerto Rico, landing a job writing for the sports magazine El Sportivo—which folded shortly after he arrived. He then applied–and was turned down–for a job at the Puerto Rican English-language daily The San Juan Star.

With no contractual writing work available, Thompson opted to became a stringer (a freelance writer working on speculation) for the New York Herald Tribune and a few other US papers; while trying to make a name for himself.

Returning to the US in 1961, Thompson visited San Francisco and eventually lucked into a living/caretaker arrangement in Big Sur, and spent the next eight months at the 375-acre Murphy Ranch. During this period, Big Sur was a “Beat” (Beatnik) haven for writers such as Henry Miller (Tropic of Cancer) and screenwriter Dennis Murphy (The Sergeant)–both of whom Thompson admired.

In the fall of 1961, Thompson had his first feature magazine article published in Playboy competitor, Rogue magazine, an over-view of the artisan and bohemian culture of Big Sur; as well as his first piece of fiction, “Burial at Sea.”

In late 1961, Thompson began work on his first novel, The Rum Diary (which was finally published in 1998 and adapted as a motion picture in 2011).

In May of 1962, Thompson relocated to South America where for the next year worked as a correspondent for the Dow Jones-owned weekly paper, the National Observer; a publication he would contribute to for the remainder of the decade. While in Brazil, Thompson also worked for the Rio de Janeiro-based Brazil Herald, the country’s only English-language daily paper.

Marriage, Drugs, Hell’s Angels

While writing for both the Observer and the Herald, Thompson’s longtime girlfriend, Sandra Dawn Conklin, joined him in Rio. Returning to the US a short time later, the couple married on May 19, 1963, and after living briefly in Aspen, Colorado, relocated to Glen Ellen, California. Their son, Juan Fitzgerald Thompson, was born in March of 1964.

That summer, Thompson began experimenting with Dexedrine (a powerful amphetamine)commonly referred to as “speed.” Thompson used Dexedrine for the next decade to influence his writing; after which he began using cocaine.

In 1965, after the Observer refused to print his review of Tom Wolfe’s 1965 book of essays, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, Thompson began writing for the Berkeley Underground Press, contributing articles to the Spide—while immersing himself in the local drug and hippie counter-culture.

That same year, Carey McWilliams, editor of the politiocultural publication The Nation, contracted Thompson to write an exposé about the Hell’s Angels motorcycle club (gang) based in California. (At the time, Thompson was living near San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury District, where the Angels were headquartered.)

The Angels article appeared in the May 17th, 1965 issue of The Nation, after which Thompson received numerous book deals–while he spent the next year living and riding with the Angels.

The relationship with the gang went sour, however, when they realized that Thompson was exploiting them for financial gain–and demanded their share. An argument ensued, resulting in Thompson receiving a sever beating (“stomping” in Angels vernacular).

In 1966, when Random House published the hard cover of Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, the dispute between Thompson and the gang was further exploited when CBC Television broadcast a face-to-face between Thompson and Hell’s Angel leader Skip Workman–before a live studio audience.

In the New York Times review of the book, it praised it as an “angry, knowledgeable, fascinating, and excitedly written book” that portrays the Hell’s Angels “not so much as dropouts from society but as total misfits, or unfits—emotionally, intellectually and educationally unfit to achieve the rewards, such as they are, that the contemporary social order offers.” Thompson himself was lauded as a “spirited, witty, observant, and original writer; his prose crackles like motorcycle exhaust.”

Fame

Following the wide-spread (and unexpected) success of the Hell’s Angels, Thompson’s writing was suddenly in great demand; his work published in several national magazines including, Harper’s, The New York Times Magazine, Pageant, and Esquire.

In 1967, shortly before the so-called “Summer of Love” was gearing-up in the Haight-Ashbury District of San Francisco, Thompson wrote a scathing piece for The New York Times Magazine called, “The ‘Hashbury’ is the Capital of the Hippies,” in which he criticized San Francisco’s hippie sector as “devoid of both the political convictions of the New Left and the artistic core of the Beats,” resulting in a “culture overrun with young people spending their time in the pursuit of drugs.” He concluded, “The thrust is no longer for ‘change’ or ‘progress’ or ‘revolution’ but merely to escape, to live on the far perimeter of a world that might have been–perhaps should have been–and strike a bargain for survival on purely personal terms.”

Disenchanted with the hippie “scene,” late in 1967, Thompson moved his family back to Colorado, renting a house in a small mountain hamlet outside Aspen called, Woody Creek.

In early 1968, Thompson joined a number of prominent writers (including Allen Ginsberg, Grace Paley, Frances Fox Piven, and Kurt Vonnegut) in signing the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, refusing to pay income tax, in protest of the Vietnam War.

That same year, Thompson used a $6,000 advance from Random House to travel the country covering the 1968 US presidential election and attend the Democratic National Convention in Chicago–collecting material. After witnessing repeated clashes between police and anti-war protesters, he stated, “I went to the Democratic Convention as a journalist and returned a raving beast.”

In early 1969, Thompson received a $15,000 royalty check for the paperback sales of the Hell’s Angels, part of which he used as down payment on the property where he would live for the remainder of his life; a 110-acre piece of land with a house he dubbed, “Owl Farm.”

In December of that year, Thompson contacted Rolling Stone editor, Jann Wenner, to compliment the magazine’s coverage of the disastrous “Altamont Free Concert,” during which four concert-goers were killed. Wenner responded with an invitation for Thompson to submit his work to the magazine, which soon after became Thompson’s primary writing outlet.

The Early 1970s, Politics, Fear and Loathing

Now a household name, Thompson used his celebrity to pursue a number of interests including a bid for Sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado, as part of a cadre of local residents seeking local offices on the “Freak Power” ticket; his primary platform, decriminalizing drugs. (Thompson lost.)

Following the notoriety of the article, “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved” in 1970, Thompson began research on the story that would ultimately bring him the most acclaim: “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan,” an exposé on the 1970 killing of Mexican-American television journalist Rubén Salazar, shot in the head at close range with a tear-gas canister by officers of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department during the “National Chicano Moratorium March” protesting the Vietnam War.

While developing the story, Thompson and prominent Mexican-American activist/attorney Oscar Zeta Acosta traveled to Las Vegas to attend a drug enforcement conference; the resulting story published in Rolling Stone in April of 1971. This and a subsequent trip to Vegas then became the basis for his book, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, which Rolling Stone serialized in two parts in November of 1971, and Random House published in book form the following year.

Written in first-person by a fictional journalist named “Raoul Duke” (accompanied by “Dr. Gonzo,” his “300-pound Samoan attorney”), the book essentially reflects Thompson’s own angst at coming to terms with the failure of the 1960s counter-cultural movement. Met with considerable critical acclaim, The New York Times praised it as “the best book yet written on the decade of dope.”

More importantly, it introduced Thompson’s “Gonzo” journalism style to a much wider readership.

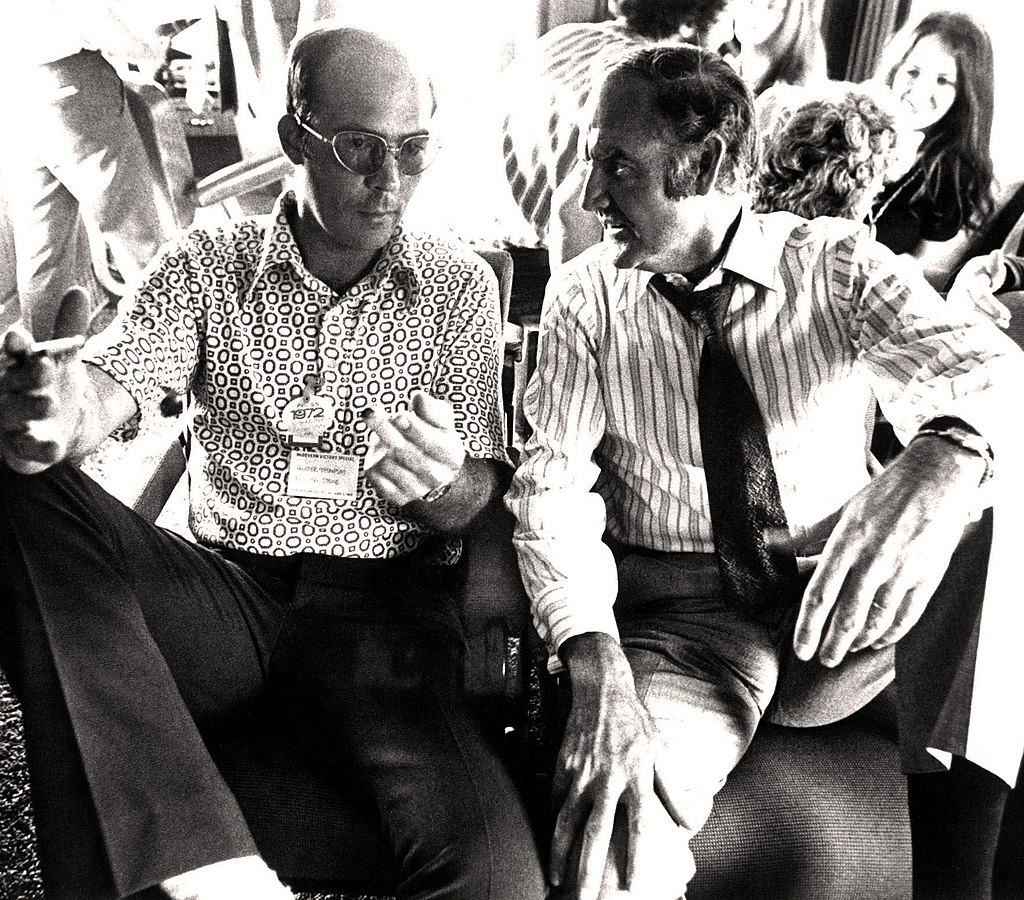

In 1971, Stone editor, Jann Wenner, assigned Thompson to cover the 1972 US presidential election, paying him a $1,000 per month retainer, and providing him a house in Washington DC; the result of which were a series of popular “Fear and Loathing” articles. (He was also offered a deal to publish a post-campaign book, which later appeared as, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’71.)

The articles, and later, the book, were praised for breaking new boundaries in political journalism, with literary critic Morris Dickstein writing, “[Thompson] had learned to approximate the effect of mind-blasting drugs in his prose style . . . He recorded the nuts and bolts of a presidential campaign with all the contempt and incredulity that other reporters must feel but censor out.”

Falling From Grace

For the next three years, as one of the most popular and in-demand writers in the Western Hemisphere, Hunter S. Thompson could do no wrong.

But soon after returning from Africa covering the “Rumble in the Jungle”–the world heavyweight boxing match between George Foreman and Muhammad Ali in 1974 (which he was too drunk to attend and never bothered to file a story)–Thompson’s writing and reputation fell into serious decline.

In 1975, Wenner sent Thompson to Vietnam to cover the final hours of the Vietnam War–but he arrived in Saigon just as South Vietnam was collapsing and the other journalists were fleeing the country. The following year, Thompson was scheduled to cover the ’76 presidential campaign (and produce a book), but Wenner had such doubts about Thompson’s commitment that he canceled it. As a result, Thompson’s primary literary output for the remainder of the decade was the first of a four-volume series of books titled The Gonzo Papers (beginning with The Great Shark Hunt, in 1979; ending with Better Than Sex, in 1994).

After 1980, Thompson produced less work, and aside from a few paid appearances, kept to his compound in Woody Creek. Despite the drop-off in contributions, Wenner kept Thompson on the Rolling Stone masthead as chief of the “National Affairs Desk” (and did so until Thompson’s death).

In 1980, Thompson divorced his wife, Sandra Conklin-Thompson, and later that year, relocated to Hawaii to write, The Curse of Lono, a Gonzo-style account of the 1980 Honolulu Marathon. The book when completed, however, was poorly received and didn’t sell; the editor calling it “disorganized and incoherent.”

Although Thompson continued to occasionally feed his Rolling Stone readers, he effectively sabotaged what remained of his reputation by submitting tasteless, often incoherent gibberish, when provided other writing opportunities.

(Thompson published these articles as Gonzo Papers, Vol. 2: Generation of Swine: Tales of Shame and Degradation in the ’80s [in 1988] and Gonzo Papers, Vol. 3: Songs of the Doomed: More Notes on the Death of the American Dream [in 1990].)

Final years

For the remaining 15 years of his life, Thompson lived as a recluse—while still managing to garner attention.

In March of 1990, Thompson faced sexual assault charges when former porn film director Gail Palmer claimed that after she rebuffed his sexual advances while visiting his home, Thompson threw a drink at her and twisted her left breast. After a police search of his home, Thompson was charged with five felonies and three misdemeanors (relating to drug possession). Two months later, the charges were dropped.

Throughout the 1990s, Thompson claimed to be working on a novel titled, Polo Is My Life; intended to be Thompson’s last major work. Although fragments of the book were excerpted in Rolling Stone, the completed novel never materialized.

Aside from a scathing obituary of Richard Nixon called “He Was a Crook,” published in 1994, Thompson’s only other notable work from this time was his final Rolling Stone feature, “The Fun-Hogs in the Passing Lane: Fear and Loathing, Campaign 2004,” a brief account of the 2004 presidential election.

Between 2003 and 2005, Thompson published his final collection, Kingdom of Fear: Loathsome Secrets of a Star-Crossed Child in the Final Days of the American Century (publicized as Thompson’s memoir).

Bringing his career full circle, between 2000 and 2005, Thompson wrote a weekly column for ESPN.com’s Page 2, called, “Hey, Rube.” (In 2004, Simon & Schuster published a collection of these columns titled, Hey Rube: Blood Sport, the Bush Doctrine, and the Downward Spiral of Dumbness.)

On April 23, 2003, Thompson married his assistant, Anita Bejmuk.

The Final Frontier

On February 20, 2005 at 5:42 pm, Hunter Stockton Thompson shot himself in the head at “Owl Farm,” while speaking to his wife on the telephone.

Per his wishes, his body was cremated.

On August 20, 2005 (also per his wishes), in a private funeral funded by actor Johnny Depp, Thompson’s ashes were fired into the sky from a cannon, while Norman Greenbaum’s “Spirit in the Sky” played.

References:

grantland.com., “Director’s Cut: ‘The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved,’ by Hunter S. Thompson,” » Director’s Cut: ‘The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved,’ by Hunter S. Thompson (grantland.com)

wwwbiography.com., “Hunter S. Thompson,” Hunter S. Thompson – Quotes, Books & Death (biography.com)

wwwthoughtco.com., “Biography of Hunter S. Thompson, Writer, Creator of Gonzo Journalism,” Biography of Hunter S. Thompson, American Journalist (thoughtco.com)

rollingstone.com., “How Hunter S. Thompson Became a Legend,” https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/rolling-stone-at-50-how-hunter-s-thompson-became-a-legend-115371/

ialjs.org., Reynolds, Bill, “On the Road to Gonzo: Hunter S. Thompson’s Early Literary Journalism (1961–1970),” https://www.ialjs.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/051-084_RoadtoGonzoReynolds.pdf

google.com., Thompson, Hunter S., Hunter S. Thompson: Fear, Loathing, and the Birth of Gonzo, https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=29vuCwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=Fear+and+Lotheing,+Paul+Perry,+free+text&ots=3I0HoP4-8J&sig=Z-otoPtyXu7ClTKDUw056MdX7IU#v=onepage&q&f=false

documentcloud.org., “The ‘Hashbury’ is the Capital of the Hippies,” https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/809208-the-hashbury-is-the-capital-of-the-hippies.html