Last updated on July 22nd, 2022 at 04:45 pm

On the 28th of June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Empire of Austria-Hungary, was assassinated in the streets of Sarajevo by a Serb nationalist by the name of Gavrilo Princip.

A diplomatic crisis between Austria-Hungary and Serbia followed, which escalated in early August into Europe’s major powers declaring war on each other.

This war pitted the Triple Entente of Britain, France, and Russia against the Central Powers of the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with many other smaller nations also involved.

The First World War would last for over four years and was the bloodiest conflict Europe had yet seen. But one of the often-overlooked aspects was that most of Europe’s heads of state were related to each other. And this wasn’t a case of them being distantly related.

Most of these individuals were either direct family members of each other or first and second cousins. So how had this strange level of consanguinity come about?

Medieval and Early Modern Antecedents

This strange interrelationship of Europe’s royal houses had a long history, stretching back into the late medieval and early modern periods between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries.

The continent’s royal families had often been content for their heirs and children to marry their subjects during the High Middle Ages. However, in the Late Middle Ages, monarchs had increasingly begun to view marriage to a member of a foreign royal house as a means of securing an alliance with a state.

Thus, for instance, King Edward III, who ruled England between 1327 and 1377 and who started the Hundred Years War with France in 1337, married Philippa of Hainault. She was the daughter of the Count of Hainault, a major state in the Low Countries during the fourteenth century, as a means of Edward securing an alliance with this necessary northern European power.

Later several of his sons took Spanish brides as England sought to secure Spanish allies against the French.

This pattern continued amongst Europe’s royal houses for centuries. By the seventeenth century, a major European king or queen would never consider marriage to any partner other than a scion of one of Europe’s other royal families.

Often this could lead to a foreign royal family taking over as rulers of another kingdom if the existing line died out. This happened twice in England.

When Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603 without an heir, the English crown passed to the Stuart royal family of Scotland, who was distantly related to the English Tudors.

Similarly, when the Stuart line died out in 1714, the British throne passed to the German House of Hanover, whose first king, George I, was descended through marriage from the Stuart line. Consequently, from 1714 the British royal family were effectively Germans.

Queen Victoria’s Children

This process of Europe’s royal families being mixed up and inter-related through marriage accelerated even further during the nineteenth century.

Much of this was owing to Queen Victoria, the long-lived ruler of Britain between 1837 and 1901. Victoria reigned at a time when the British Empire was the pre-eminent global power.

Britain ruled over Canada, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Australia, New Zealand, and a considerable amount of Africa. The sun never set on the British Empire, so the saying went, and the Royal Navy controlled the world’s oceans.

As a result of its hegemonic position, all of Europe’s royal families wanted a marriage alliance with Britain. And Victoria was more than able and willing to facilitate this.

She had nine children with her husband, Prince Albert, who was himself a member of the German royal house of Saxe-Coburg. These children married scions of all the major royal houses of Europe.

They created a massive web of interrelationships between the European royal lines in ways that would impact the First World War.

For instance, Victoria’s eldest child, a daughter whom she named Victoria after herself, married Prince Frederick of Prussia, the largest of the German states, in 1858.

Prussia later led the formation of the German Empire in 1871, and Frederick became Emperor Frederick III in the 1880s.

Victoria’s brother, the future King Edward VII of Britain, married Princess Alexandra of Denmark in 1863.

Another notable marriage involving Victoria’s children was the union of her son Alfred with the Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia in 1874.

Moreover, the marriages of Victoria’s nine children resulted in 42 grandchildren, which in turn married into additional royal lines.

Thus, Victoria’s grandchildren became kings, queens, emperors, and empresses of a list of countries which included Britain, Germany, Russia, Spain, Romania, Greece, and Norway.

Unsurprisingly, Victoria has often been referred to as the ‘Grandmother of Europe’.

Who Was Related to Who?

Needless to say, this level of intermarriage meant that Europe’s royal families were very closely related when the war broke out in 1914.

For instance, one of Queen Victoria’s sons, Prince Alfred, was a father to Prince Alfred of Saxe-Coburg in Germany, Queen Marie of Romania, the Grand Duchess Victoria of Russia, Princess Alexandra of Hohenlohe in Germany and Princess Beatrice of Galliera of Spain, meaning these brothers and sisters were aristocrats and royals of opposing sides in the war.

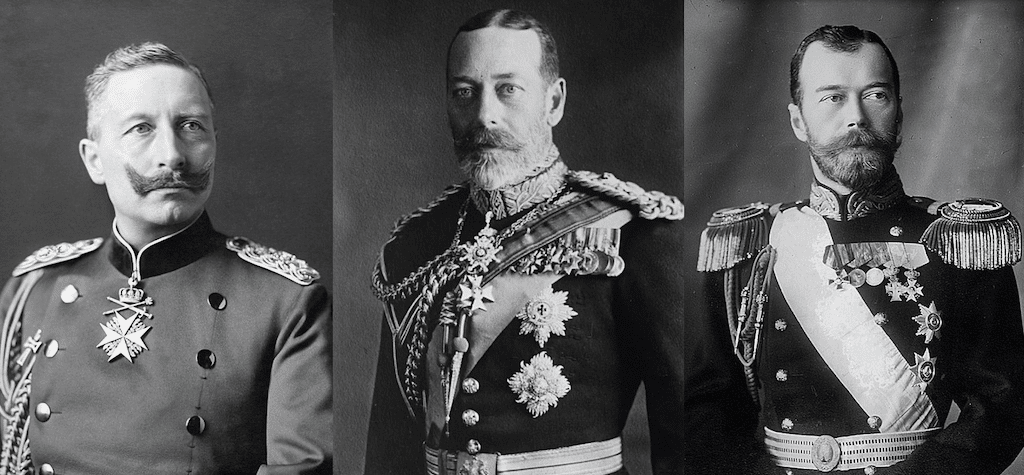

However, the most important relationship was between the rulers of three of the largest states in the war. These were King George V of Britain, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, and Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany.

These three were first cousins, Wilhelm’s mother Victoria, George’s father Edward, and Nicholas’s mother Alice, all having been brother and sisters. Thus, as heads of state and kings and queens went, the First World War was a family affair.

Implications of World War One Being a Family Affair

The outbreak of the First World War had major implications for the royal lines of Europe. Aspersions were cast on the royal family in some circles in England on account of their being heavily related to the German imperial family.

Indeed, because the Hanoverians, which had claimed the British throne in 1714, were effectively a German family, many people viewed the royal family as being German themselves.

However, patriotism and duty to the crown made this a minority view. Others were not so well protected. For instance, members of the German House of Battenberg, which had married into the British royal family during Victoria’s reign, lived in England in 1914.

They faced extensive xenophobia and their loyalty was suspected once the war broke out. To combat this, the head of the family, Prince Louise of Battenberg, changed the family name to Mountbatten and relinquished his German titles during the war.

In other instances the interrelationships caused one of Queen Victoria’s descendants to pull his or her nation in a particular direction during the war. Such was the case with Queen Marie of Romania.

Her country remained neutral in 1914, but she eventually coerced the government of Romania to ally with Britain, France and Russia, as her family affinities still lay with Britain.

Thus, the interrelationship of Europe’s heads of state during the First World War was both complex and influential in the course of the conflict.