The strange and tragic history of Japan’s attempt to bomb the United States during World War II began with a summer picnic.

It began just outside the small town of Bly, Oregon, on a secluded forest road. Reverend Archie Mitchell was with his wife Elsie and five children from their Sunday school class at the start of what they surely thought would be a beautiful Saturday.

Surrounded by mountains covered in old-growth pine and fir, and with the sun shining down through the trees, it should have been an idyllic day.

But as Reverend Mitchell was parking the car, Elsie and the children gathered around a strange-looking gray object lying on the ground at the edge of the forest. The children called out excitedly and bent down.

Just as one of them reached out to touch it, Reverend Mitchell turned to shout a warning. But in that very same instant, an explosion ripped through the bodies of all five children and Elsie, setting them ablaze and turning them into twisted heaps of flesh and bone.

When forest rangers from up the road noticed the flying debris from the blast, they rushed down and found Reverend Mitchell desperately trying to put out his wife’s flaming clothes with his bare hands. She remained alive for just a few minutes before dying.

The four boys, who had been standing closest to the object, were all killed instantly. Little Joan Patzke only had time to take a final couple of breaths before she too passed away.

At that moment, the small group of men, surrounded by the strange, fiery scraps of metal, paper, and dead bodies, had no idea what had just happened.

In the coming weeks, they, along with the rest of the country, would soon discover that this was just one of several thousand bombs sent by Japan from across the vast Pacific Ocean in an attempt to strike at the heart of the United States.

The tragic deaths in Bly shook the local community. Unfortunately, it would not be the last time one of these bombs would be found.

The Origins of Japan’s Fire Bomb Program

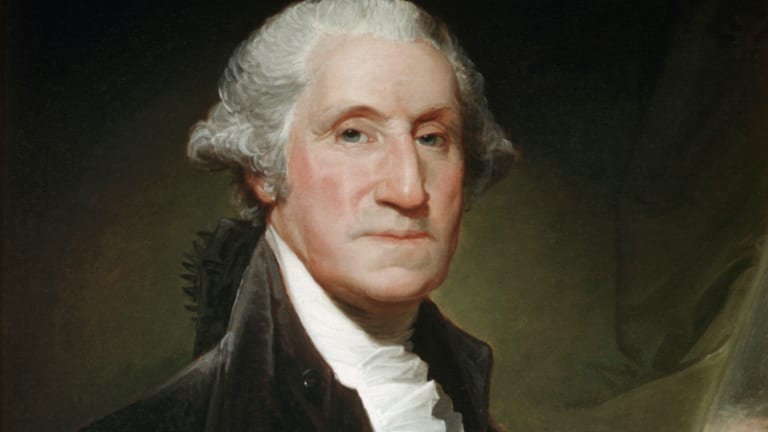

In the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States struck back against Japan with a bold bombing run.

It was the first time that bombers took off from an aircraft carrier. The pilots, led by Lieutenant Colonel James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, weren’t sure if they’d be able to take off with only the few hundred yards that the carrier’s main deck offered them.

Fortunately for the Americans, the 16 bombers took off successfully. They met little resistance as they spread out across Japan dropping their payloads on Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, Kobe, and Nagoya.

The attack, which has come to be known as the Doolittle Raid, did minimal damage to Japan’s infrastructure. Psychologically, however, it was devastating. The Japanese people felt betrayed by a government that had promised they would be invulnerable to any foreign attack.

To boost morale, the Japanese military decided it needed to strike back at the United States. They began developing a program that would later be called fusen bakuden, or “fu-go” for short. This was a program aimed to replicate the damage perpetuated by the Americans on Japanese soil.

The development of the “fu-go” balloons took place at the Noborito Institute. The principal aim of the institute was to develop high-tech covert weapons for the Japanese military.

Among some of the projects underway at Noborito were a small, unmanned tank; rocket-propelled explosives; and a so-called “death ray” that was designed by the famous Czech-born Nikola Tesla.

The balloon program at Noborito began in the 1930s. It was originally designed to be carried out from submarines that would launch the balloons just off the coast of the United States.

As the war in the Pacific grew in scale and intensity, the military decided it couldn’t spare any subs for the experimental attack. The researchers at Noborito had to come up with another solution.

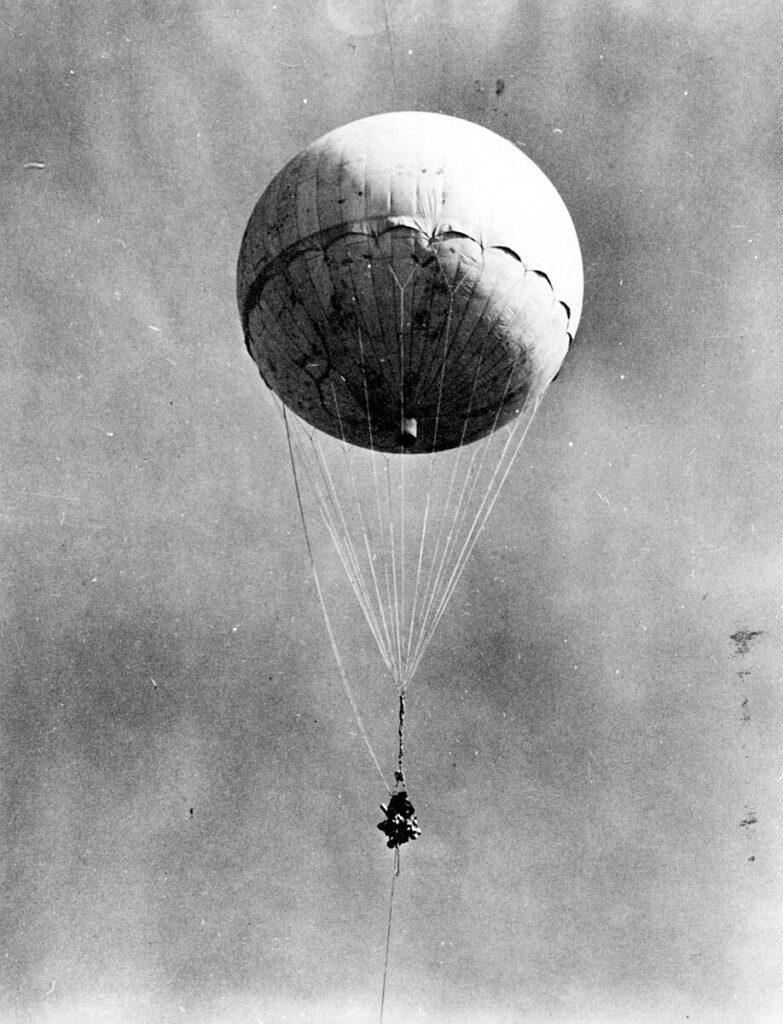

Eventually, they figured out that by using the Pacific jet stream, they could conceivably launch balloons from the Japanese mainland. They used an automated ballast mechanism that dropped sandbags depending on the balloon’s altitude variations. The balloon would then be able to cross the entire Pacific Ocean and drop its payload on the western coast of the United States.

However, the Japanese military knew it had no way of controlling the balloons as they made their long journey. To make sure that all of their efforts would be worth it, they decided they would need to manufacture 10,000 balloons.

By their estimates, only about 10% of those would reach the United States. Of those, only a fraction would release their bombs and ignite.

They hoped that the small fraction of balloons that did eventually land in the United States would be able to cause forest fires across the heavily forested Pacific coast. The Doolittle Raid had sewn fear and doubt among the Japanese population.

Now it was Japan’s turn to do the same to their enemy.

Fire Bombs on North American Soil

After years of research and testing, by 1944 the fu-go balloons were finally ready to make their much-anticipated crossing of the Pacific.

The first launch took place on November 3, 1944. Over the coming weeks, the U.S. Navy found more and more strange-looking debris off the western coast of California.

The FBI began looking into the matter but soon handed the investigation over to the military when the nature of the balloons and their origin became apparent. At this point, government officials didn’t know what to make of the balloons and some feared that they contained deadly biological weapons.

As the military carried out its investigation, the Office of Censorship decided to keep any knowledge of the balloons from the American public. They reasoned that if they allowed the media to make any reports about the Japanese attack, that information could be used as propaganda.

That decision made sense strategically, but it had serious consequences for those who stumbled upon the deadly bombs in remote areas of the western United States. After all, if the Mitchell family had known about the possibility of balloon bombs, they might have never been killed.

It was not until the tragic deaths of Elsie and the five Sunday school children that the U.S. government finally decided to warn the public about the balloon bombs.

It was an understated message in which they made sure to clarify that the bombs did not represent a very significant threat to United States security, but that anyone who found one should notify the government.

In the end, the Japanese balloon attack was an ambitious project that ultimately failed to achieve its objectives.

Japanese leaders hoped to spark conflagrations throughout the Pacific Northwest. They wanted to cause panic among the population. But the most that they achieved was to kill six innocent citizens, five of whom were children.

As the Allied forces closed in on Berlin in the following months, the balloon episode began to fade from Americans’ collective memory. Now, the years-long attempt by the Japanese to bomb the United States using balloons has been relegated to a footnote in history.

But it’s one that some families will not soon forget.