Last updated on July 22nd, 2022 at 04:42 pm

On the 31st of October 1517, the Professor of Moral Theology at the University of Wittenberg, a man called Martin Luther, nailed a document to the door of All Saint’s Church in the town of Wittenberg.

This document, known today as Luther’s ’95 Theses’, contained a series of arguments against the Papacy’s sale of indulgences. These were certificates granting the buyer a remission of their sins.

Luther’s decision to nail his ’95 Theses’ is typically viewed as the start date of the Protestant Reformation, a movement for religious reform which transformed the religious, political, social, cultural, and even economic life of Europe over the next century.

But what is curious about Luther’s actions and those of other religious reformers who emerged in the 1520s and 1530s, such as Huldrych Zwingli and Jean Calvin, is that their ideas had all been developed before.

For example, in England in the 1380s, a reformer called Jon Wycliffe had made the same arguments about the moral decline of the Roman Catholic Church.

He was soon followed by another religious maverick called Jan Hus in Bohemia in what is now Czechia in the 1410s. So what made Luther different?

The answer is that he had access to the printing press and the revolutionary innovations which had been introduced to the European publishing industry in the mid-fifteenth century by the man known as Johannes Gutenberg.

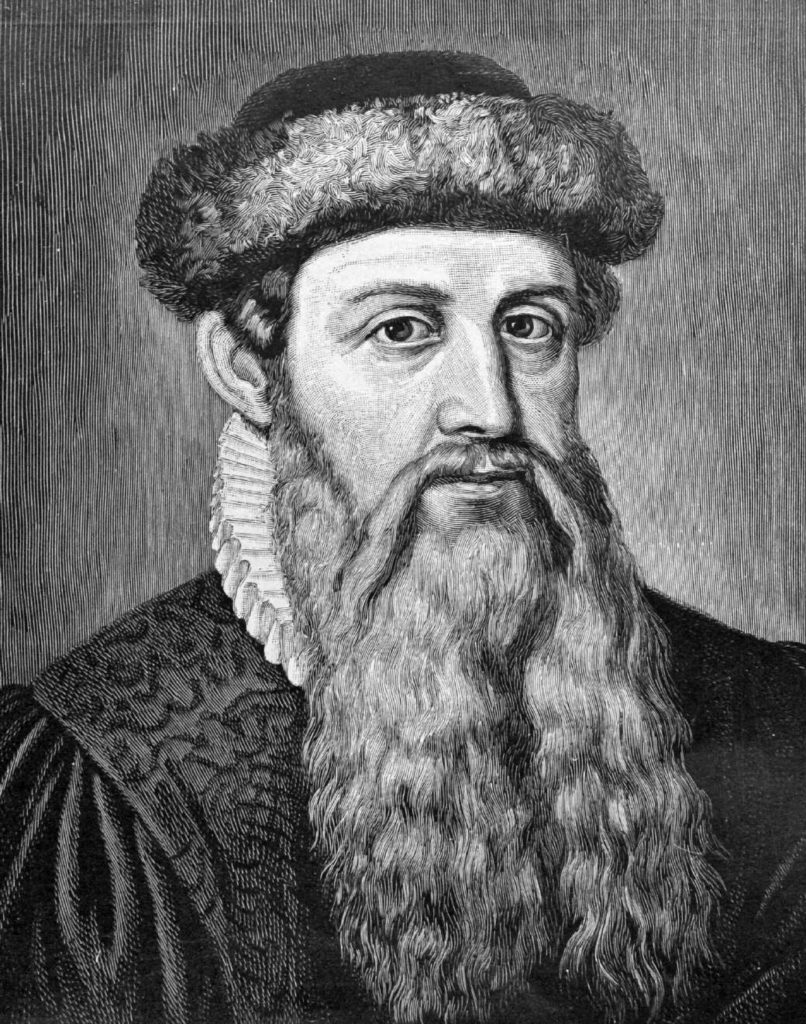

The Early Life of Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gutenberg was born in Mainz in western Germany sometime around 1400. But unfortunately, very little is known about his childhood and early life.

We do know that by 1437 he was living in the city of Strasbourg, not far from Mainz but located in eastern France today.

Here he had become a craftsman, one who seems to have primarily worked as a goldsmith. However, there is evidence that he also worked as a gem-cutter and as a metallurgist, one who made metallic objects as part of the growing consumer society emerging across Europe as the continent transitioned from the Middle Ages into the Renaissance.

As part of this, he was involved in many business ventures in the early 1440s—one of these involved efforts to devise a new way of printing books.

Block Printing in Fifteenth-Century Europe

It is essential to understand what print technologies were available to fifteenth-century Europeans before looking at how Gutenberg introduced innovations to these.

By the time of Gutenberg’s birth, around 1400, printing of a rudimentary kind was being practiced in Europe.

This was known as block printing, whereby a printer carved out the text of an entire page onto a wooden slab.

You would press the wooden slab in ink before pressing the slab against a sheet of paper. When this was done, the ink would transfer onto the page and create a page of text.

The slab would then be used repeatedly to replicate this page hundreds of times. This was technically an early printing technology, but it was extremely cumbersome, as a printer had to carve out the text on a wooden slab painstakingly for each page of a given book.

This type of ‘block printing’ could require weeks, months, or even years to produce all of the slabs, depending on how large the book was.

The Invention of Moveable Type

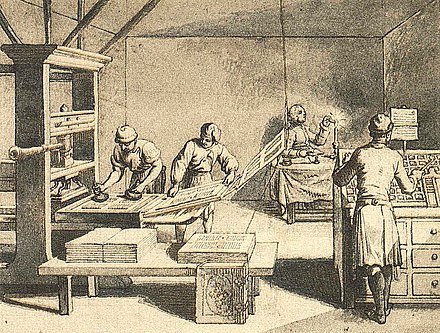

Gutenberg revolutionized the printing trade in the early 1440s. He did so by inventing a new printing technology called ‘moveable type.’

‘Moveable type’ involved having hundreds of tiny metal pieces. One end of the pieces was the shape of a letter of the alphabet.

Hundreds of these metal pieces were arranged in a specific fashion in lines within a metal frame. This arrangement spelled out the text of an entire page of a book.

A printer could lock them in, dip them in ink and print an entire page. Then, after printing hundreds of pages, the letters could be rearranged, and the process started over again. Replacing the laborious process of carving out a new page from a wooden slab made it far quicker to print an entire book.

Moreover, because the printer only needed to rearrange the pieces of moveable type to produce a new page rather than carving out a wooden slab, the job required far less skill.

Gutenberg invented this printing system using a moveable type in Strasbourg in the early 1440s. Thus, he did not develop the concept of printing, as this was already being practiced with block prints. But he did revolutionize the technology used to print.

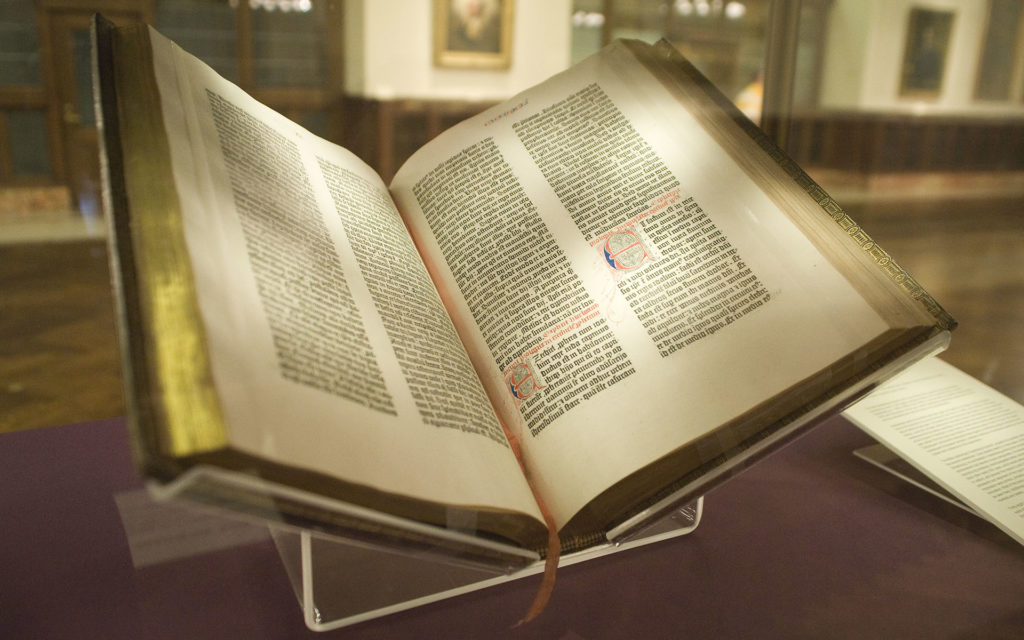

The Gutenberg Bible

Gutenberg had finished devising the technology of moveable type by the late 1440s.

Around this time, he moved back to his native Mainz. He printed copies of a German poem in 1450 in his workshop of Humbrechthof in the city.

He also acquired funding for his endeavors from a wealthy financier, Johann Fust.

With this, Gutenberg set about a grand project to use the technology he had developed to publish copies of the Bible. He appears to have produced 180 copies of the text, a small number which is explained by his decision to print the books on vellum or calf skin, an expensive material.

The text was finished by 1454 or 1455. It gained considerable attention when it was published, with a copy exhibited at the Frankfurt Book Fair, the largest book fair in Europe.

As such, its appearance served to popularise Gutenberg’s invention and the technology of moveable type began to spread.

Gutenberg’s Later Life and the Printing Revolution

Despite the significance of his invention, Gutenberg did not achieve great riches during his lifetime.

He was honored by the Archbishop of Mainz for it in the 1460s and given a large pension to sustain him in his later years, but he was far from wealthy when he died in 1468.

Despite this, his invention transformed early modern Europe and the wider world. Moveable type spread through Germany in the late 1450s.

By the end of the 1460s, the new printing method was being used in printer’s workshops in Paris, Rome, and Venice, while the 1470s saw its arrival to cities like Lyon, London, Milan, and Antwerp.

By the 1480s, it was being used as far away as Stockholm in Sweden. By 1500 printing presses throughout western and central Europe had already produced 20 million volumes using Gutenberg’s moveable type.

By 1600, a century later, more than 200 million volumes had been published.

In the process, Gutenberg’s invention transformed European history.

Not only did it facilitate the spread of the Protestant Reformation, but also the Scientific Revolution, the Medical Revolution, and the Renaissance, as writings by figures such as Martin Luther, Jean Calvin, Galileo, Niccoló Machiavelli, Leonardo da Vinci, William Shakespeare, and Miguel de Cervantes were published and distributed much more widely than would have ever been possible prior to the appearance of Gutenberg’s moveable type.

As a result, today, copies of Gutenberg’s Bible sell for upwards of forty million dollars.