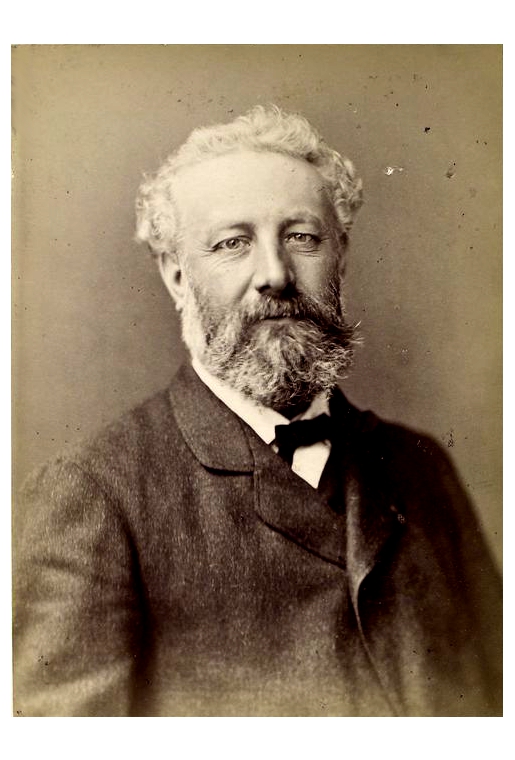

Novelist, poet, playwright, and songwriter. Jules Verne was one of the most prolific writers in history.

He was, no doubt, best known for his wildly-popular adventure novels, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Journey to the Center of the Earth, Around the World in Eighty Days, and The Mysterious Island. Several of these were made into major motion pictures.

Considered one of the founding fathers of the science fiction genre, Verne’s approach to writing was a unique melding of factual science and fictional adventure. He invariably imagined a variety of innovations and technological advancements decades before they were practical realities.

Nantes, France

Jules Gabriel Verne was born on February 8, 1828, in the port city of Nantes, to attorney Pierre Verne, and Sophie Allotte de La Fuÿe, one of two sisters from a family of local navigators and shipowners.

In 1829, the Verne family moved from the home of Sophie’s maternal grandmother Dame Sophie Marie Adélaïde Julienne Allotte de La Fuÿe to Quai Jean-Bart. This was where Verne’s brother Paul was born that same year. Followed by sisters Anne in 1836, Mathilde in 1839, and Marie in 1842.

School and Early Inspiration

In 1834, at the age of six, Verne was sent to a boarding school in Nantes. It was operated by Madame Sambin, the widow of a naval captain who disappeared some 30 years before. Sambin often told the children that her husband was a shipwrecked castaway who’d eventually return from his desert island paradise, like Robinson Crusoe.

This “shipwrecked” theme would stick with Verne throughout his life and appear in several novels including, The Mysterious Island (1874), The School for Robinsons (1882), and Second Fatherland (1900).

In 1836, Verne attended the Catholic École Saint-Stanislas. He quickly distinguished himself in the subjects of mémoire (recitation from memory), geography, Greek, Latin, and singing.

That same year, his father bought a vacation house in the village of Chantenay (now part of Nantes) on the Loire River. In his memoir, Souvenirs d’enfance et de jeunesse (Memories of Childhood and Youth), Verne recalls his fascination with the river and the vessels that navigate it.

Verne also vacationed at his uncle Prudent Allotte’s house at Brains. He was a retired shipowner who’d traveled the world. Verne enjoyed playing the board game “Game of the Goose” with his uncle. Both the game and his uncle’s name were later memorialized in two novels, Robur the Conqueror (1886), and The Will of an Eccentric (1900).

In 1840, the Vernes moved again, this time to a large apartment at Rue Jean-Jacques-Rousseau. That same year Verne attended the seminary, Petit Séminaire de Saint-Donatien.

Then from 1844 to 1846, he and his brother Paul were enrolled in the Lycée Royal (now the Lycée Georges-Clemenceau). This was a public secondary school in Nantes. Verne received his certificate of completion in July of 1846.

Writing vs. the Study of Law

By 1847, at the age of 19, Verne began writing his first serious work. He wrote Un prêtre en 1839 (A Priest in 1939), based on his experience at Petit Séminaire de Saint-Donatien, and two verse tragedies, Alexandre VI (Pope Alexander VI) and La Conspiration des poudres (The Gunpowder Plot).

To redirect Verne’s interests toward the study of law, his father sent him to Paris to focus on law. His father assumed he would eventually inherit the family law practice. A short time later he passed his first-year exams.

But rather than devote his time to pursuing his degree, Verne used his family clout to enter Paris society. His uncle Francisque de Chatêaubourg introduced him to the world of “literary salons.” These were social gatherings hosted by French intellectuals to discuss literature and philosophy.

For the next three years, Verne fed his newly discovered passion for theater by writing numerous plays. He worked with French composer Jean-Louis Aristide Hignard, for whom he wrote a lyric to be set to music.

He was doing this while fighting bouts of stomach cramps (possibly, colitis), facial paralysis (caused by a chronic middle ear inflammation), and trying to avoid his obligation to enlist in the French army.

Despite having no intention to practice law, in January of 1851, Verne achieved his law degree.

Literary Debut

One useful consequence of his time spent frequenting salons was making the acquaintance of French Playwright Alexandre Dumas fils.

After showing him a manuscript for a stage comedy called Les Pailles rompues (The Broken Straws), the two young men revised the play. Dumas had it produced by the Opéra-National at the Théâtre Historique, in Paris. It opened on June 12, 1850.

The following year, Verne met Pierre-Michel-François Chevalier. He was editor-in-chief of the magazine, Musée des familles (The Family Museum). He was seeking stories featuring geography, history, science, and technology.

Verne offered him a short historical adventure called, “The First Ships of the Mexican Navy.” Chevalier published it in July 1851. Then a few months later he published “A Voyage in a Balloon.”

A combination of adventurous narrative, travel themes, and detailed scientific research, “A Voyage . . .” would become the template for many major works to follow.

Elements of His Craft

Verne began to frequent the Bibliothèque nationale de France. He spent time researching the individual elements that would constitute the components of his adventure tales. Particularly science topics and the latest discoveries (especially in geography).

During this period, Verne met the famed writer and explorer Jacques Arago. Even though he lost his sight in 1837, he continued to travel extensively. The two men became close friends. Arago’s scintillating accounts of world travel led Verne toward the development of a new literary genre, “travel writing.”

“Roman de la Science”

In 1852, Verne had two new pieces published in Musée des familles: Martin Paz.

The first was a novella set in Lima, Peru. And “Les Châteaux en Californie, ou, Pierre qui roule n’amasse pas mousse” (“The Castles in California, or, A Rolling Stone Gathers No Moss”). This was a one-act comedy cleverly laced with sexual innuendos.

In April and May of 1854, the magazine published two of Verne’s short stories, “Master Zacharius” and “A Winter Amid the Ice.”

At this point, Verne began formulating an idea for a new kind of novel. He called it a “Roman de la Science” (“novel of science”). This allowed him to incorporate large amounts of factual, science-based information.

Meanwhile, Verne’s father pressed him to abandon writing and get down to the business of lawyering.

In the Name of Love

In May of 1856, Verne traveled to Amiens, in northern France, to attend the wedding of boyhood friend, Auguste Lelarge. While there, he found himself attracted to the bride’s sister, Honorine Anne Hébée Morel. She was a 26-year-old widow with two young children.

Needing to present himself as a “man of means” to formally court Mme Morel, Verne accepted an offer to work for stock broker, Fernand Eggly. This was a full-time position as an agent de change on the Paris Bourse (securities market).

Winning the favor of Morel and her family, Verne and Morel were married on January 10, 1857.

Essentially leading a double life, Verne rose early each morning to write before going to the Bourse. He published his first book, Le Salon de 1857 (The 1857 Salon), and conducted scientific and historical research in the evenings.

Voyages to Fuel the Imagination

In July of 1858, Verne and composer Jean-Louis Hignard took advantage of an offer extended by Hignard’s brother, Auguste. The offer was to take a sea voyage from Bordeaux to Liverpool to Scotland. The journey would be Verne’s first trip outside France.

Upon return to Paris, Verne fictionalized his experiences to form the framework of a semi-autobiographical novel, Backwards to Britain (published in 1889).

In 1861, Verne and Hignard took another voyage, this time to Stockholm (Sweden) and then Norway. Adding to his growing imagination, Verne continued to develop his “Roman de la Science.” The story that eventually developed was an African-set adventure called, Five Weeks in a Balloon (published in 1863).

That same year, Michel Jean Pierre, Verne and his wife’s only child, was born.

Pierre-Jules Hetzel

In 1862, Verne met publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel. This was the man who would essentially put Verne and his writing on the literary map.

They formed a writer/publisher collaboration that would span decades. Hetzel saw the commercial value in Verne’s writing that ultimately lead to the creation of Voyages extraordinaires.

This was a series of short stories and adventure novels that included The Adventures of Captain Hatteras (1864/1866), Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1872).

Hetzel’s goal with Voyages was to “outline all the geographical, geological, physical, historical and astronomical knowledge amassed by modern science and to recount, in an entertaining and picturesque format . . . the history of the universe.”

Verne’s fastidious attention to detail and scientific trivia, coupled with his natural sense of wonder and imagination, easily met Hetzel’s vision.

Part of the appeal of Verne’s adventures was that readers could genuinely learn science and geography (as well as geology, biology, astronomy, paleontology, oceanography, and history) while visiting exotic lands and cultures around the globe. Some referred to Verne’s works as “encyclopedic novels.”

In all, fifty-four of Verne’s novels were published during his lifetime, between 1863 and 1905. Many of which became part of the Voyages series.

Rude Awakening

For the first several years of their collaboration, Hetzel influenced many of Verne’s novels. Verne was happy to have his work published. So he blindly agreed to his suggestions.

But in 1869, a conflict regarding the storyline of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea awakened Verne to the reality that he and Hetzel were not equal partners. He realized that Hetzel wielded all control.

Verne had planned to make his protagonist, Captain Nemo, a Polish scientist whose acts of vengeance were directed against the Russians for killing his family during the “January Uprising.” This was a true-life insurrection in Russian-controlled Poland.

But Hetzel objected to villainizing the Russian people. So Nemo’s motivation was left a mystery. From that time on, the relationship between the editor and writer was strained. Hetzel outright rejected many of Verne’s creative intentions.

Even with the ongoing resentment, Verne published two or more volumes each year (per contract). The most successful were, Journey to the Center of the Earth, From the Earth to the Moon, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, and Around the World in Eighty Days.

Final Years

On April 9, 1870, Verne was made a knight of France’s Legion of Honour. On July 19, 1892, he was promoted to the rank of Officer.

By 1872, Verne was successful enough to live on income derived from his writing alone. But most of his wealth came from the stage adaptations of Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (in 1874) and Michel Strogoff (1876). He wrote these with French playwright, Adolphe d’Ennery.

On March 9, 1886, Verne entered his home. His twenty-six-year-old mentally deranged nephew, Gaston, shot at him twice with a pistol. The first bullet missed. The second entered Verne’s left leg and caused permanent damage. Gaston spent the rest of his life in a mental asylum.

In addition to his leg injury, Verne later suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body. He also fought chronic diabetes for the remainder of his life.

Death

On March 24, 1905, Verne died at the age of 77 at his home in Amiens, France, at 44 Boulevard Longueville. It is now renamed Boulevard Jules-Verne, in his honor.

His son, Michel Verne, oversaw the publication of the novels Invasion of the Sea and The Lighthouse at the End of the World, after his father’s death. The Voyages extraordinaires series continued for several years under Michel’s management until it was discovered that he had altered his father’s stories. He was consequently forced to extricate himself.

Legacy: Verne, the Visionary

Fans of Verne’s work often cite the esteemed writer’s ability to seemingly see into the future. It seems like he predicted the advent of technology and societal development. For example:

- Space Flight: Verne was one of the first writers to attempt to scientifically prove the possibility of space travel. He wrote extensively about it in From the Earth to the Moon, Around the Moon, and Hector Servadac.

- Modern Cities: In the 1860s, Verne wrote a dystopian look at life in 20th Century Paris. In it, he describes a world where society only values technology and commerce. People live and work in skyscrapers, and cars and high-speed trains are typical. This piece was rejected for publication.

- Computers, the Internet, Fax Machines: In Paris in the 20th Century, Verne describes sophisticated electrically-powered computers that perform various complex tasks in banks. They are able to transfer information over great distances. Essentially, computers using the Internet. Other machines called “photographic telegraphy” are essentially fax machines.

- Video Calling/Skyping: In “One Day in the Year of an American Journalist in 2889,” Verne describes a device called a “phonotelephot.” With this, two individuals can visually and audibly communicate—no matter where they are located.

- Weapons of Mass Destruction: In his novel, Five Hundred Million Begums, the antagonist creates a giant cannon. It launches projectiles containing liquefied carbon dioxide which when evaporated, dramatically lower the temperature. This causes “any living creature within thirty meters of the explosion must inevitably die from this chilling temperature and from suffocation.”

Legacy: Acknowledgments and Accolades

During the 20th Century, Verne’s works were translated into more than 140 languages. This made him one of the world’s most translated authors.

Dozens of famed writers credit Verne with inspiring them to write, including Ray Bradbury. He is quoted as saying, “We are all, in one way or another, the children of Jules Verne.”

Beginning in 1916, with 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, many highly successful motion pictures were made from Verne novels. These included The Mysterious Island (1929 and 1961), From the Earth to the Moon (1958), Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959), and perhaps the most popular, Around the World in 80 Days (1956).

Verne’s fans find it no surprise that his influence extends beyond literature and film. His influence extends into the world of science and technology. He continues to inspire scientists, inventors, and explorers.

In 1954 the US Navy launched the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, christening it Nautilus.

Additionally, real-life adventurers like journalist Elizabeth Cochran Seaman (a.k.a. Nellie Bly), aviator Wiley Post, and businessman/aviator/sailor Steve Fossett, have all attempted to circumnavigate the globe in record-breaking times, ala Verne’s fictional hero, Phileas Fogg.

Verne is credited with helping inspire the literary, theatrical, and social movement that romanticizes science fiction based on 19th-century technology known as Steampunk.

References

Britannica, “Jules Verne,” Jules Verne | Biography & Facts | Britannica

Evans, Arthur, B., “Jules Verne and the French Literary Canon,” https://scholarship.depauw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1060&context=mlang_facpubs

Pérez, de Vries, Margot, “Jules Verne FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions,” Jules Verne FAQ [English] (gilead.org.il)

Biography.com., “Jules Verne,” https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/jules-verne

WorldPredictions.com., “How Jules Verne predicted the future in his works,” How Jules Verne predicted the future in his works (theworldpredictions.com)