In May of 1962, the relatively unknown pop artist Andy Warhol was featured in Time magazine with his painting, “Big Campbell’s Soup Can with Can Opener (Vegetable).” That became Warhol’s first painting displayed in a museum, exhibited at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut in July of 1962.

On July 9, 1962, Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans exhibition opened at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, California. This opening marked his US West Coast debut.

In November of that same year, Warhol was given an exhibition at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery in New York City. This included the works “Gold Marilyn,” eight of the classic Marilyn series (also referred to as Flavor Marilyns), “Marilyn Diptych,” “100 Soup Cans,” “100 Coke Bottles,” and “100 Dollar Bills.”

“Gold Marilyn,” (a 6′ 11” x 4′ 9” silk-screened gold-painted canvas immortalizing the deceased actress Marilyn Monroe) was purchased by post-modern architect Philip Johnson. It was donated to the Museum of Modern Art. (In 2022, “Gold Marilyn” sold for $195 million).

These exhibits and the media coverage they elicited are how most of America discovered Warhol and his unique approach to “pop” art.

By the mid-1960s, Warhol’s art was among the most recognizable in the world.

Humble Beginnings

Warhol was born Andrew Warhola Jr., on August 6, 1928, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He was the fourth child of Ondrej Warhola, Sr. and Julia (née Zavacká), Austria-Hungary immigrants.

Warhol’s father emigrated to the US in 1914 and his mother in 1921. Like many Slovakian immigrants living in Pittsburgh at that time, his father worked in a coal mine; his mother worked as a maid.

Warhol had two elder brothers: Pavol “Paul” (born in Hungary), and Ján. (The Warhola’s first child died before moving to the US).

Muse and Motivation

In the third grade, Warhol contracted Sydenham’s chorea. This is an autoimmune disease that causes involuntary movements of the face, hands, and feet. It is often associated with scarlet fever.

Confined to bed, Warhol passed the time drawing, listening to the radio, and snipping pictures of movie stars from Hollywood glamour magazines. Warhol later described this period as very important in shaping his personality, skill set, and personal preferences.

About this time, his parents bought him a Brownie camera—which essentially ignited his creativity.

When Warhol was 13, his father died in an (undisclosed) accident.

Education

In 1945, Warhol graduated from Schenley High School in North Oakland, winning a Scholastic Art and Writing Award. He intended to study art education at the University of Pittsburgh in hopes of becoming an art teacher.

Instead, he enrolled in the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). There, he studied commercial art.

While there, Warhol served as art director for the student art magazine, Cano. He illustrated a cover in 1948, and a full-page interior illustration in 1949. (These are believed to be his first published artworks.) That same year he graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in pictorial design.

A short time later, Warhol moved to New York City and began a career in magazine illustration and advertising.

Becoming a Commercial Artist

In the late 1940s, Warhol received his first commission; drawing shoes for Glamour magazine. His work caught the eye of shoe designer Israel Miller, renowned for his elegant women’s shoes, who hired him as an illustrator.

Referring to Warhol’s work of this period, American photographer and pop artist John Coplans said, “Nobody drew shoes the way Andy did. He somehow gave each shoe a temperament of its own, a sort of sly, Toulouse-Lautrec kind of sophistication, but the shape and the style came through accurately.”

While working in the shoe industry, Warhol developed his “blotted line” art technique. This was a method of applying ink to paper then blotting the ink while still wet. The technique is akin to the printmaking process, (prints created by transferring ink from a copper matrix to a sheet of paper).

His use of tracing paper and ink allowed him to replicate the same basic image multiple times and create endless variations.

In 1952, Warhol was given his first one-man show, at the Hugo Gallery in New York City; but his work was not well received. Even so, he (and his art) began attracting influential patrons of the arts who showed him around.

They introduced him to others who could help promote his work. Most notably: the artists’ agent, Emile de Antonio, and director of the Leo Castelli Gallery, Ivan Karp.

In 1956, Warhol’s work was included in a group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

The following year, after what critics began calling his “whimsical” style, his ink drawings of shoe advertisements were shown at the Bodley Gallery in New York City. Now the City’s art community began to take notice.

Transition and Techniques

Warhol became interested in the special effects achievable by using an epidiascope (or opaque projector). This is a device utilizing mirrors, prisms, and/or imaging lenses. It is capable of projecting images of both opaque and transparent objects.

He began experimenting with prints by famed art photographer Edward Wallowitch. He began to transform the artist’s “First Boyfriend” photograph by tracing contours and hatching shadows.

Warhol then used a variation of Wallowitch’s “Young Man Smoking a Cigarette” for a book cover he submitted to Simon and Schuster for the Walter Ross pulp novel, The Immortal. This work led to being hired by RCA Records to design album covers and promotional materials.

In 1962, Warhol learned silk-screen printing from American artist Max Arthur Cohn, becoming an early proponent of the silk-screen printmaking process. In May of that year, Warhol and his work was featured in Time magazine—effectively introducing him and his art to the world at large.

“The Factory”

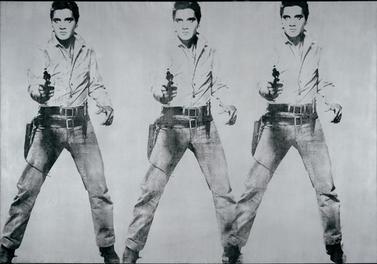

In early 1963, Warhol rented his first studio in an old firehouse. This is where he began work on his now-famous Elvis series. These, along with his series of Elizabeth Taylor portraits, were shown at his second exhibition at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, California.

Later that year he relocated his studio to East 47th Street in New York City. This would become his (in)famous space, “The Factory.” This giant studio became a popular hang-out for artists, writers, musicians, and other celebrities—including David Bowie, Jim Morrison, Bob Dylan, Keith Haring, Liza Minnelli, Lou Reed, and Mick Jagger.

Boxes, Boxes

In the spring of 1964, Warhol was given his second exhibition at the Stable Gallery. This featured sculptures of commercial product boxes stacked and scattered throughout the space to resemble a warehouse. Warhol said of the idea, “When you think about it, department stores are kind of like museums.”

Warhol had wooden boxes custom-made. Upon these, he then silk-screened images onto: “Brillo Box,” “Del Monte Peach Box,” “Heinz Tomato Ketchup Box,” “Kellogg’s Cornflakes Box,” “Campbell’s Tomato Juice Box,” and “Mott’s Apple Juice Box”—which sold for $200 to $400 each, depending on size.

Pop art dealer Paul Bianchini was inspired by the success of Warhol’s commercial product exhibit. So that fall he created the American Supermarket exhibition, held at his Upper East Side gallery.

The exhibit replicated a typical small supermarket except that everything in it—the produce, meat, canned goods, and adverts on the wall–were created by prominent pop artists of the time: Bob Watts, Claes Oldenburg, Mary Inman, and, of course, Andy Warhol.

For this event, Warhol designed a $12 paper shopping bag—plain white with a red Campbell’s soup can rendered—priced at $1,500.

The event was an unqualified success.

Warhol’s Entourage

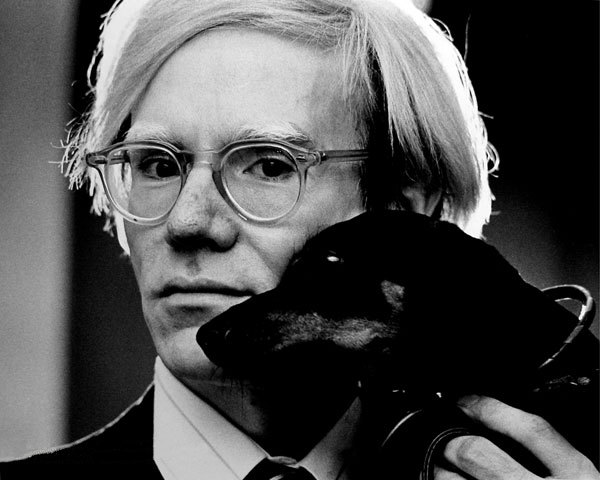

More important than the avant-garde art Warhol created was, perhaps, the eccentric bohemian image he cultivated.

He essentially created his own entourage (individuals he called his “superstars”). The list included the model Nico, gay subculture sex symbol Joe Dallesandro, fashion model Edie Sedgwick, American actress Viva, French artist Ultra Violet, transgender actress Holly Woodlawn, actress-singer Jackie Curtis, and American actress Candy Darling.

By the end of the 1960s, Warhol was working day and night on his paintings. He was using silk screens to mass-produce images the way corporations mass-produced consumer goods.

To increase production output, he enlisted his “superstars.” He also enlisted the help of a revolving collection of adult film stars, drag queens, socialites, drug addicts, and musicians willing to be part of his “art.”

Not only did these “art-workers” help him create his famous paintings, but they also starred in his Factory films. They maintained the constant circus-like atmosphere Warhol thrived in, and did as much to promote Warhol’s career as his art itself.

Warhol Films

Beginning in 1963, Warhol began making short films; often shot inside “The Factory.”

In all, he directed or produced more than 300 silent, black & white, and color films. These include Sleep (1963), Blowjob (1964), The Life of Juanita Castro (1965), Salvador Dali (1966), Imitation of Christ (1967), Lonesome Cowboys (1968), Blue Movie (1969), and Trash (1970).

Most of his cinematic projects were never viewed outside “The Factory.” But, in 1972 Warhol produced a comedy-drama film written and directed by American director Paul Morrissey called Heat (a parody of the 1950 film, Sunset Boulevard).

This drew considerable attention in American art houses. It was also well received at Cannes and the New York Film Festival screening where attendance was standing-room-only. Famed actor and director Otto Preminger called Heat, “depressingly entertaining.”

In 1973, Warhol agreed to lend his name to a Paul Morrissey horror film. The film would star German character actor Udo Kier, Joe Dallesandro, 1950s fashion model Maxime McKendry, Italian actress Stefania Casini, and Italian actor Vittorio de Sica, called Blood for Dracula.

Conceived by famed director Roman Polanski, Polanski convinced Morrissey to shoot it in 3-D (requiring viewers to wear special 3-D glasses). While Polanski contributed to the project (and even played a small part in the film), Warhol is believed to have had no involvement whatsoever.

Renamed Andy Warhol’s Dracula, it was a minor hit in both West Germany and the US in 1974, despite an “X” rating due to nudity, gore, and obsessive violence. The LA Times described the film as “aesthetically pleasing” and “pretty funny up until that Grand Guignol finale.”

In 1977, Warhol produced what would be his final film, Andy Warhol’s Bad. This was a comedy starring the famous American actress Carroll Baker, TV and film actor Perry King, and renowned Broadway actress Susan Tyrrell. Though the concept for the film was Warhol’s (who invested $1.5 million), he had little to do with writing or production.

The opening screening of Bad, in May 1977, attracted over 750 A-Listers including Warren Beatty, Jack Nicholson, Julie Christie, and George Cukor. Kevin Thomas of the LA Times said, “The film isn’t so bad as it is merely morbid and depressing.”

In the end, Warhol’s most memorable films are those he had little to do with.

The Assassination Attempt

On June 3, 1968, radical feminist writer Valerie Solanas (author of the 1967 SCUM Manifesto which advocated the elimination of all men) shot Warhol (two or three times). She also shot art critic-curator Mario Amaya at “The Factory.”

Prior to the shooting, Solanas was an occasional figure at “The Factory” scene. She had even appeared in the 1968 Warhol film I, a Man.

While Amaya received only minor injuries (and was released from the hospital the same day), Warhol was seriously wounded and nearly died. For the remainder of his life, he would suffer the physical effects of the attack and be forced to wear a surgical corset.

Warhol’s inner circle say the assassination attempt had a profound effect on his attitude and art.

The 1970s: the Dark Period

For Warhol, the 1970s was a much less eventful decade than the 1960s.

In 1971 he was given a “retrospective” exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. This took place in the famous “Meatpacking District” of Manhattan in New York City.

In 1973, he created his now-famous portrait of Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong (second only in popularity to his Marilyn series). Neither accomplishment drew the attention of the decade before.

Warhol spent much of the 70s making appearances at various New York City nightclubs like Max’s Kansas City and Studio 54. He was soliciting new, rich patrons for portrait commissions—successfully attracting the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Mick Jagger, Liza Minnelli, John Lennon, Diana Ross, and Brigitte Bardo.

In 1977, Warhol was commissioned by art collector Richard Weisman to create Athletes, ten portraits of the leading athletes of the day. But aside from the Mao portrait, none of Warhol’s creations raised an eyebrow.

The 1980s: Resurgence

Essentially rediscovered by new and emerging artists of the time (Jean-Michel Basquiat, Julian Schnabel, Francesco Clemente, David Salle, Keith Haring, and Enzo Cucchi), Warhol experienced a renaissance of sorts. Graffiti artist Fab Five Freddy paid him homage by painting an entire train with Campbells soup cans.

At the same time, however, critics were panning him as nothing more than a “business artist.” They were condemning his 1980 exhibit, Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century displayed at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan; labeling them “superficial.”

Warhol didn’t help matters by saying, “Making money is art, and working is art and good business is the best art.”

During this period, Warhol took an interest in television and produced two cable shows, Andy Warhol’s T.V. (1980–1983) and Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes (1985–1987) for MTV. Both enjoyed moderate success.

Before the 1984 Sarajevo Winter Olympics, Warhol was teamed with 15 other artists (including David Hockney and Cy Twombly) to contribute a “Speed Skater” print to the Art and Sport collection. The resulting image was used as the official Sarajevo Winter Olympics poster.

That same year, Vanity Fair commissioned Warhol to produce a portrait of rock star Prince to accompany an article celebrating the success of “Purple Rain” and the movie of the same name. “Orange Prince” was created using the same method he used to create the Marilyn “Flavors” series in 1962.

In September of 1985, Warhol’s joint exhibition with Basquiat, called Paintings, opened at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery, in New York City. But it was met with negative reviews.

In January of 1987, Warhol traveled to Milan, Italy for the opening of what would be his final exhibition: Last Supper, at the Palazzo delle Stelline.

In February of that year, Warhol and jazz great Miles Davis modeled for Koshin Satoh’s fashion show at the Tunnel in New York City. (Critics thought it an odd pairing.)

An Untimely Death

For an untold period of time, Warhol had been suffering from chronic gallbladder problems. Afraid to be hospitalized, he delayed seeing a doctor. Finally diagnosed, on February 20, 1987, he was admitted to New York Hospital where his gallbladder was removed.

Despite appearing to be recovering, Andy Warhol died in his sleep from a sudden postoperative irregular heartbeat just two days later, on February 22, 1987. He was 58.

More than 2000 people attended the memorial service held at St.Patrick’s Cathedral.

Charging the hospital with malpractice, Warhol’s family sued the facility for inadequate care. They say that the arrhythmia was caused by improper care and water intoxication. Quickly settled out of court, Warhol’s family received an undisclosed sum of money.

Legacy

Shortly after Warhol’s death, a museum dedicated to his work was established in his hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Understandably, Warhol strongly influenced a number of musicians. This included David Bowie (a regular visitor to “The Factory”) who wrote the song, “Andy Warhol” dedicated to him. Also, Lou Reed, who wrote “Style it Takes” and “Stranger In A Strange Land” (with the band Triumph); as well as Simple Minds’ “Killing Andy Warhol.”

In 2002, the US Postal Service issued an 18-cent stamp commemorating Warhol.

In March of 2011, a chrome statue of Andy Warhol was revealed at Union Square in New York City.

In 2012, a crater on the planet Mercury was named after Warhol.

In 2013, to honor the 85th anniversary of Warhol’s birthday, the Andy Warhol Museum and EarthCam launched a collaborative project titled “Figment,” a live feed from Warhol’s grave.

Dozens of biographies and exposes have been written including, (A biography of) Warhol, written by art critic Blake Gopnik in 2020.

Warhol is featured as a character in Miracleman comics.

References

Therake.com., “ANDY WARHOL: POPPING WITH CONTRADICTORY STYLE,” https://therake.com/100-greatest-rakes/andy-warhol-popping-with-contradictory-style/

Biography.com., “Andy Warhol,” Andy Warhol – Death, Art & Facts (biography.com)

Warhol.org., “Andy Warhol,” Andy Warhol – The Andy Warhol Museum

Acocella, Joan, The New Yorker, “Untangling Andy Warhol,” Untangling Andy Warhol | The New Yorker

Warholart.gallery, “Andy Warhol Biography,” Andy Warhol Biography (warholart.gallery)