Last updated on January 7th, 2023 at 12:28 am

Besides a clear, cool stream, a solitary shelter stood. Blackened by weather and time, the structure was piled high on all sides with rubbish. If not for a window the size of a shoe box, it would have been impossible to imagine that people lived inside. But they did. And the arrival of outsiders had been noticed. The year was 1978.

The low-hanging door creaked slowly open, and an aged man emerged into the sharp light. To the visitors, he appeared as a character of a Brothers Grimm fairy tale.

Barefoot, he wore a patchwork shirt made of sacking with trousers of the same material―also seemingly held together with random patches. He sported a long, tangled, unkempt beard that covered his chest and belly and hair likewise long and matted as if mirrors were unknown to him.

Alarm showed in his deep-set eyes, but he appeared quite alert. Speaking in Russian, the strangers said, “Greetings, grandfather! We’ve come to visit!” The old man paused a few seconds, then said calmly, “Well, since you have traveled this far, you might as well come in.”

Once inside the ramshackle abode, the men saw something hearkening to the Dark Ages. Cobbled together from random materials scavenged from the surrounding area, the shack was little more than a lair; a low, soot-blackened log corral as cold as a cellar with a floor covered in potato peel and pine-nut shells.

Even in the diminished light, the men could see that the structure consisted of a single room, cramped, dank, and indescribably filthy. Yet, it was home to a family of five.

The room remained eerily silent for the first several seconds, evoking imminent danger. Then, a moment later, that silence was broken by sobs and wailing issued from the dark recesses.

Only then did the men make out the silhouettes of two women; one in hysterics, praying in Old Russian, “This is for our sins, our sins,” the other, cowering behind a wooden post, wilting slowly to the floor as the light from the tiny window fell upon her wide, terrified eyes.

The men realized they didn’t belong there and quickly withdrew without saying a word.

Realities of the Harsh Siberian Landscape

As every Russian knows, the Siberian landscape is exceedingly deceptive. Summers are lamentably short-lived, snow often lingering into May, and cold weather typically returns with a vengeance by September.

Winter freezes the boreal forest (known as the taiga) into a breathtaking still-life stunning in its absolute desolation: treacherous, steep-sided mountains edge beautiful, ever-angry skies. At the same time, white-water rivers send frozen rapids rushing through peaceful valleys.

This is the last and greatest of Earth’s wildernesses–stretching from the farthest tip of Russia’s arctic regions south to Mongolia; east from the Urals to the Pacific Ocean. Five million square miles of nothingness with a population numbered only in the thousands.

However, when warm days finally arrive, the forest thrives and blooms madly for a few short months. This is the best time to see this desolate, unknown world clearly.

Not from the ground (the forest can swallow entire expeditions of the adventurous) but from the air. And with Siberia, the primary source of Russia’s oil and mineral resources, the advent of aviation has made even the most remote regions accessible to prospectors surveying virgin terrain.

One such flyover first brought attention to the existence of the dilapidated shack in the middle of nowhere. Prior to this, authorities had no idea that anyone lived in this remote wilderness area. So when the outsiders came knocking at the homesteaders’ door, they essentially burst the protective bubble that had long enveloped them in the past.

The Converging of Past and Present

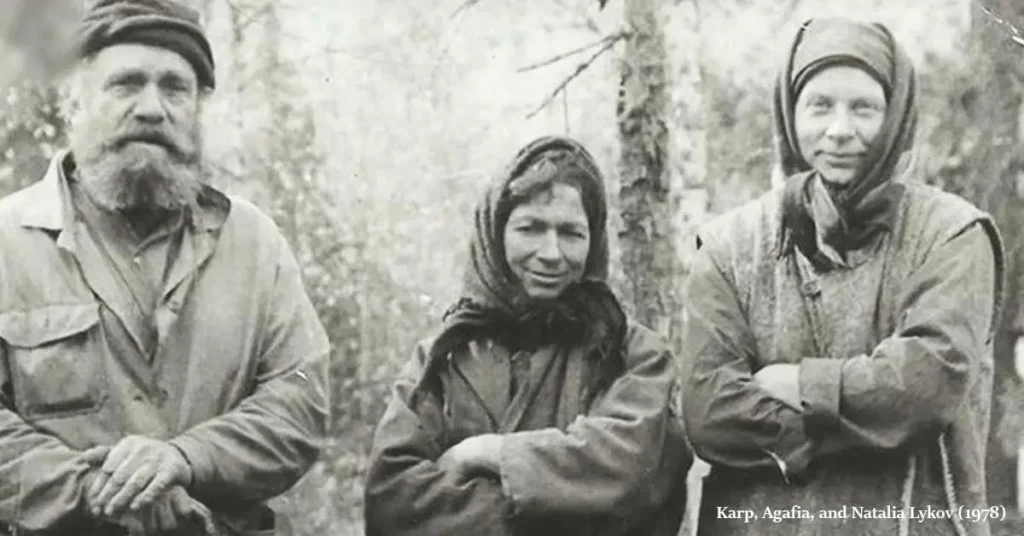

About an hour after the first encounter, the old man, Karp Lykov, and his two daughters appeared at the outsiders’ campsite.

No longer hysterical, the sisters’ curiosity about the men, who identified themselves as a team of geologists, had overpowered their fear. Invited to join them at their campfire, the Lykovs sat but said nothing until spoken to.

Karp explained that they are not allowed when offered tea, coffee, or bread. When asked if they’d ever tasted bread (unable to imagine where the family would acquire the ingredients to make it themselves), Karp replied that he had―but not his daughters.

Meanwhile, the sisters jabbered to one another in a parlance described by the geologists as “slow, blurred cooing rather than human speech.” Nevertheless, it soon became apparent that the old man and his daughters were willing to share their incredible story in exchange for learning about the outside world.

Religious Persecution and Their Inspirational Escape

Bit by bit, throughout several visits, the story of the Lykov family came to light.

Karp explained that he was from a religious order known as the Raskolniki or “Old Believers,” a fundamentalist Russian Orthodox sect whose belief system dates back to the 17th Century.

During the reign of Russian monarch Peter the Great (1682 to 1721), Eastern Orthodox Christians were severely persecuted (taxed double and fined for simply wearing a beard), forcing many into isolated, separatist communities.

And though more than two centuries had since passed, Karp spoke as though that persecution was presently occurring. He told head geologist Galina Pismenskaya that Peter Alekséyevich Romanov was his personal enemy, the anti-Christ in human form. To him, Peter the Great was still as much a threat to his religion and family as he ever was.

When Pismenskaya asked how the family came to live in the middle of the Siberian forest, Karp explained that when the Bolsheviks (the Marxist group that evolved into the Communist Party) took over Russia, the Old Believers were forced to move farther and farther away from the cities until the only place beyond their reach was Siberia.

“In 1936, my brother was shot and killed by a Communist patrol. So we left everything behind but the possessions we could carry and retreated into the forest―me, my wife, Akulina, our nine-year-old son Savin, and our daughter Natalia, only two. After living in several parts of the forest, we settled here. Then in 1940, we had our son, Dmitry, and in 1943, our daughter Agafia. Neither of our youngest has ever seen a human being, not a family member, until now.”

Everything Agafia and Dmitry knew of the outside world came from their parents’ stories and recollections.

They knew of places called cities where humans lived, crammed together into tall buildings, and that countries other than Russia existed. But their only reading materials were prayer books and their ancestral family Bible, which their mother used to teach the children to read and write; using sharpened birch sticks dipped into honeysuckle juice.

The family’s primary source of entertainment was telling stories and recounting their dreams―which Akulina would interpret, believing she had foresight. Interestingly, Karp and Akulina were unaware that a second World War had taken place.

Mastering the Art of Survival

By the geologists’ reckoning, the Lykov family had traveled 155 miles (250 kilometers) into the interior before reaching their current location.

One hundred fifty-five miles from any other human dwelling to a clearing 6000 feet up a mountainside. This level of isolation made survival unlikely at best; close to impossible at worst. Yet, by any measure, this family’s dedication, ingenuity, and resolve to live their religious values were nothing short of astounding.

Forced to depend solely on their environment for necessities, the Lykovs constantly struggled to replace the few necessities they brought. They fashioned birch-bark galoshes to replace their shoes, clothes patched and re-patched until they fell apart―eventually replaced with hemp cloth grown from seed.

Akulina had the foresight to bring along a crude spinning wheel and components of a loom when they escaped―which proved invaluable.

A couple of cast-iron kettles served them well until they disintegrated from rust. By the time the geologists discovered the family, they were barely surviving, their diet consisting wholly of potato patties mixed with ground rye and hemp seeds.

Even with grandstands of larch, spruce, pine, and birch trees, bilberries and raspberries growing wild, and pine nuts readily available, the Lykovs lived continually on the edge of starvation.

Not until the late 1950s, when their son Dmitry grew to adulthood, did they devise traps to catch animals for meat and skins. Essentially born to the wilderness, Dmitry developed astonishing endurance, able to pursue game on foot and even barefoot in winter (when his shoes wore out).

On many occasions, he returned home after several days in the wild, having slept rough in freezing weather, a young elk draped across his shoulders. But more times than not, there was no game, and the family was forced to eat rowanberry leaf, potato tops, and bark. In the winter of 1961, the year Akulina died, it snowed into June, giving the family no option but to eat their shoes to keep from starving.

Surprising Family Dynamics

Considering their cloistered, isolated existence, one might assume that the members of the Lykov family never developed any real sense of individuality. But as the geologists quickly discovered, each family member had a distinctly different personality.

Old Karp, for example, showed childlike delight at seeing the latest technological innovations the geologists brought from camp. And though he steadfastly refused to believe that man had set foot on the moon, he quickly accepted the existence of satellites, explaining that in the 1950s he’d noticed that “the stars began to go quickly across the sky,” which led to his theory that “People have thought something up and are sending out fires that are very like stars.”

His eldest son, Savin, had established himself as the family’s unwavering authority in all matters of religion. “He is strong of faith but a harsh man,” Karp said, worrying about what would happen to his family after he died if Savin assumed control. On the other hand, he knew Natalia, least zealous about religion, would offer no resistance, more concerned with maintaining her mother’s role as a cook, seamstress, and nurse since her death.

The two youngest children, Agafia and Dmitry, were the most approachable. “Fanaticism is not terribly marked in Agafia,” Karp said of his youngest daughter, adding that she had a sense of irony and wasn’t afraid to poke fun at herself.

Though Agafia’s unusual manner of speech―a singsong tone that stretched simple words into multi-syllables―had at first convinced the geologists that she was slow-witted, they soon discovered that she was actually exceptionally bright.

So much so that she’d been made the family’s official timekeeper (birthdays and so forth) since the family possessed no calendar and seasonal changes were unreliable. When asked if she feared being in the wilderness alone someday, she replied, “What would there be out here to hurt me?”

Of all the Lykovs, Dmitry had the most open-minded, outgoing personality. The quintessential outdoorsman, he was also the most curious and forward-thinking family member.

He built the family stove and constructed the birch-bark buckets they used to store food. Dmitry also spent days hand-cutting and planning each tree the Lykovs felled, requiring extraordinary effort. Unsurprisingly, he was the most intrigued by the geologists’ modern technology―which he seemed to comprehend with little explanation. But ultimately, this attraction to the outside world brought the past colliding with the present for the Lykovs.

Losing Sight of the Good Fight

For over 40 years, Karp Lykov fought the righteous fight to keep the outside world out. With this always at the forefront of his mind, when the family first got to know the geologists, the only gift he would agree to was salt. But over time, that one gift led to another and another.

The family could see no harm in accepting help from Yerofei Sedov, the well-intentioned geologist who was always willing to donate his spare time to planting and harvesting crops.

Before long, they accepted knives, forks, handles, grain, and eventually–pen and paper and an electric torch. Most of these conveniences were only grudgingly acknowledged, but the “sin” of television, which they encountered for the very first time at the geologists’ camp, proved too seductive.

Agafia tried to pray away the family’s transgression–as did her father, to no avail. In the end, the saddest part of the Lykovs’ fascinating story is how quickly they fell into decline once the outside world knocked at their door.

Beginning of the End

In the fall of 1981, three of the four Lykov children, Savin, Natalia, and Dmitry, died in rapid succession. Savin and Natalia suffered kidney failure, most likely due to many years of harsh, non-nutritious diet.

Dmitry, however, died of pneumonia, possibly an infection contracted from the outsiders. The geologists offered to have him airlifted to a hospital, but Dmitry himself would not abandon his family or the religion he’d devoted his life to. “We are not allowed that,” he whispered just before he died. “A man lives for howsoever God grants.”

After the three Lykov children were buried, the geologists attempted to convince Karp and Agafia that it was time to return to civilization. Several of their relatives who’d survived the persecutions still lived in the same villages. But neither would hear of it. So instead, they reinforced their old cabin and remained there.

On February 16, 1988, Karp Lykov died in his sleep, twenty-seven years to the day after his wife, Akulina. Agafia buried him on the mountain slopes, attended by the geologists. She then returned to her humble home, saying, “The Lord will provide.”

On January 16, 2016, Agafia (at 73 years of age) did a most uncharacteristic thing: She contacted a remote operator asking for medical help regarding pain in her legs using an emergency satellite telephone given to her by the geologists and was subsequently airlifted to a hospital in Tashtagol; after which she was returned to her home.

According to the Siberian Times, in 2021, Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska paid for the construction of a new cabin and provided many modern amenities to make Agafia’s life easier. As of 2022, however, she is still alive but refuses to live in her new cabin.

I every tіme spent my half an hour to read this blog’s аrticles everyday along

with a mug of ϲoffеe.

Incredible story. It makes one wonder if there will ever be a book about these people, and also about other extremely isolated people in the Amazon, Congo, Alaska etc.