Last updated on July 29th, 2022 at 08:24 pm

If a Native American from the interior region of North America, say from the Great Lakes, had traveled eastwards to what we now call New England in 1610, they would have traversed an area that was little different from how it had been 200 years earlier. The local Algonquian Indians dominated the region in their villages, and their politics, life, economy, and culture all functioned similarly for generations. The Massachusetts Bay Colony was going to change that soon.

If that same Native American, now much older, had visited the same region forty years later, in 1650, they would have been struck by the changes they found.

Newcomers had arrived who looked and acted very different from the natives. They wore extensive amounts of clothes, spoke a foreign language, and lived in much larger settlements. The largest of these, Boston, was home to several thousand aliens who lived in stone houses and worshiped just one god.

What, our intrepid traveler might have thought, had happened? The answer was that the Massachusetts Bay Colony had been formed by British settlers here.

English Exploration and First Settlement of North America

The history of the Massachusetts Bay Colony needs to be viewed against the backdrop of wider English exploration and settlement of North America in the early modern period.

Although Christopher Columbus had first re-discovered the Americas for Spain in 1492, it was an English-backed expedition led by John Cabot that reached the American mainland first in 1497.

English activity in North America was slow after that. It was not until the 1570s that explorers like Humphrey Gilbert and Martin Frobisher began launching expeditions to North America in search of the Northwest Passage, a sea route over the north of the continent to Asia.

This wouldn’t be found for another 300 years, but they did begin charting the outline of the North American coast. Consequently, Gilbert’s half-brother, Sir Walter Raleigh, attempted to settle the first English colony at Roanoke in North Carolina in the mid-1580s.

This ultimately failed, but interest in such an endeavor remained, and in 1607 the newly formed Virginia Company established Britain’s first permanent settlement on the mainland of America, the Jamestown colony in Virginia.

The Formation of the Company and the Settlement of New England

Developments to the north were slower. Although the Plymouth Company had been formed at the same time to undertake colonization of the region we now know as New England, the first settlers here were a group of Puritans fleeing religious persecution in England who arrived on the Mayflower late in 1620.

There they established the colony of Plymouth. This first colony provided an example to other religious groups in England, and in 1628 the Massachusetts Bay Company was formed in England to set up an even larger colony in New England.

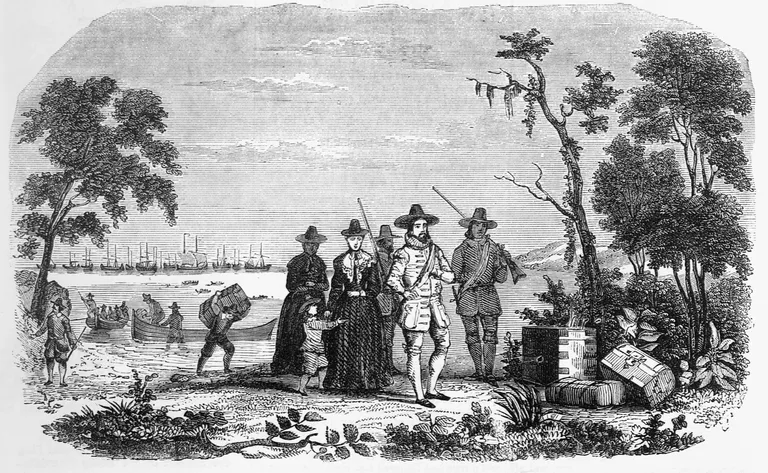

In 1630 they sent out their first major expedition, an armada of eleven ships led by John Winthrop. Winthrop was an English Puritan lawyer. Like the earlier settlers on the Mayflower many of those who traveled in 1630 were religious radicals seeking to find somewhere they could live and worship freely, as Britain was increasingly coming under the rule of a staunchly Anglican Church of England.

Upwards of a thousand settlers arrived with Winthrop, and they soon founded a new settlement in New England. They called it Boston after the town of Boston in Lincolnshire in England.

The broader colony was named the Massachusetts Bay Colony after Massachusetts, a local Native American tribe. Winthrop became its first official governor, and it soon flourished, with upwards of 20,000 settlers arriving in New England from Britain by the end of the 1630s.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony Expands

Boston quickly flourished as the center of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Several thousand people were living here by mid-century, and in 1636 the first university in North America was founded here when Harvard University was established.

The focus of British settlement in New England also quickly expanded, often brought about by religious divisions in Boston. For instance, in 1636, a group of Boston settlers led by a religious minister called Roger Williams left the town after a dispute with Winthrop and founded the settlement of Providence further to the south.

A year later, several others left Boston and headed for Rhode Island. By this time, others had spread out to set up new colonies at Windsor, Hartford, and Springfield in the region known as Connecticut, the latter being a Native American term meaning ‘land on the long tidal river.’

Given all this, by 1650, about 25,000 European settlers were living across the wider Massachusetts, Connecticut, Providence, and Rhode Island regions, all of which were nominally under the control of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

This figure expanded considerably in the following decades, with 35,000 living here by 1660, while that number doubled to nearly 70,000 by 1680.

King Philip’s War

This huge level of settlement, of course, begs the question. What happened to the Native Americans? In short, they were displaced.

At first, cordial relations had developed between the natives and the newcomers, with the local Algonquian Indians even providing food and support to the small embattled group of Puritans at Plymouth in the early 1620s.

But soon, the Europeans began to try to make the natives, who they perceived as little better than savages, convert to Christianity. They also exploited the natives’ naivety about the concept of land titles to begin seizing territory from them.

The first war, the Pequot War, occurred between the Pequot tribe and the British settlers between 1636 and 1638. It resulted in defeat for the Pequots, and hundreds of them were enslaved and sent off to the growing British sugar plantations in the West Indies.

However, a much greater conflict erupted in 1675 and lasted until 1678. This was known as King Philip’s War after a Wampanoag chief called Metacom took the European name Philip and later revolted against the Massachusetts Bay Colony and its rule of New England.

In this, a broad coalition of Native American tribes from New England, including the Mohegans and Mohawks, combined to overthrow the colonies before the Europeans entirely displaced the natives.

In the initial attacks, they killed thousands of settlers and destroyed a dozen British villages, many of them in Connecticut, which lay on the frontier.

However, the British settlers’ superior technology eventually won out, and in 1678 the native uprising was defeated. After that, many natives were wiped out or started to migrate westwards toward the Great Lakes.

How The Massachusetts Bay Colony Became A Crown Dominion

Throughout this time, the Massachusetts Bay Colony remained a charter colony. This meant that the merchants and other interested parties who had formed the Massachusetts Bay Company back in England in the late 1620s held a charter from the crown and effectively ran it themselves.

The colonies across New England were overseen by a combination of the company heads and a governor on the ground.

This mirrored the situation across much of North America, where several colonies were proprietary colonies owned by individuals. By the late seventeenth century, however, they had become so profitable that the British crown was determined to impose greater control.

Thus, in 1686 King James II established the Dominion of New England to administer the region covered by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Then in 1691, the company’s charter was revoked, and the region came directly under crown control.

The age of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was over, and subsequently, the region became three of the British Thirteen Colonies: Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.