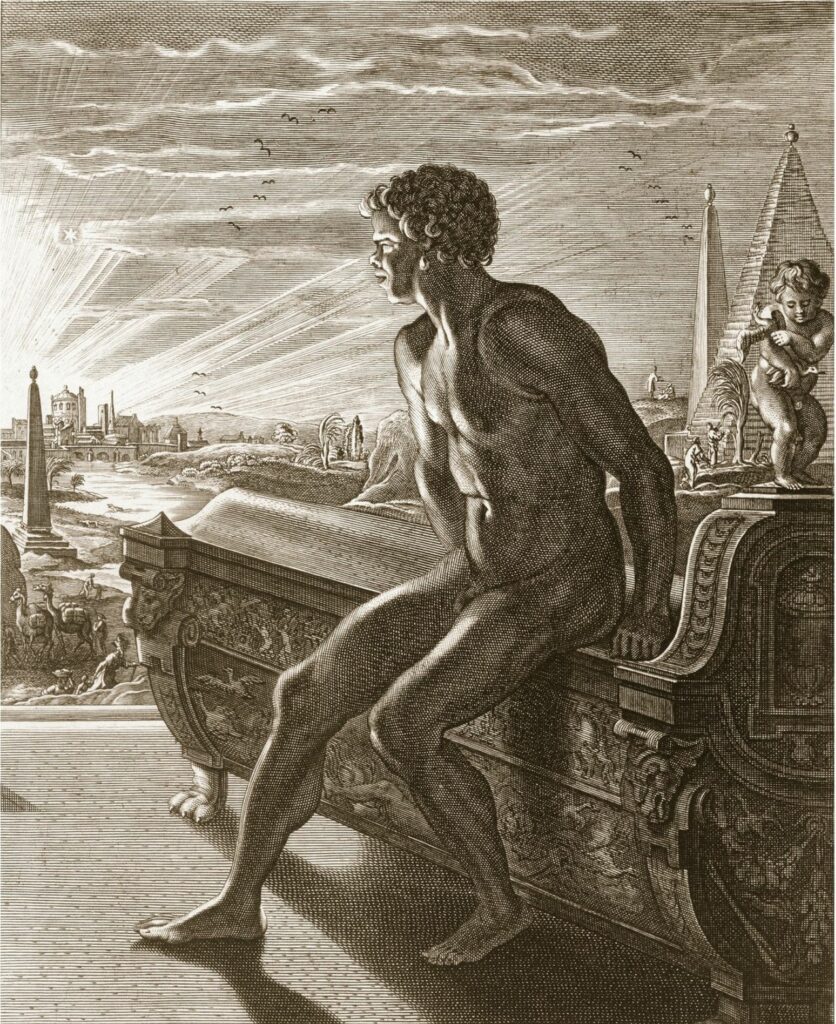

Memnon was known to the ancient Greeks as the greatest African warrior who ever lived. Born of a goddess and a prince, he grew up to become king of the land of Ethiopia.

When he brought his vast army of warriors to Troy to aid in the defense of the city, the beleaguered Trojan king welcomed him with open arms. They hoped that if anyone could put an end to the destructive Greek siege, it would be him.

In the end, that hope was misplaced. Out on the battlefield, Memnon met his match against Achilles, whose near-complete invulnerability allowed him to slay his rival.

But centuries later, Memnon’s legacy lives on in the story of the Trojan War and the magnificent stone monuments that the ancient Greeks called the Colossi of Memnon.

Memnon in Greek Mythology

According to Greek legend, Memnon was a powerful warrior whose mother was Eos, the goddess of the Dawn.

He appears in the saga of Troy as a would-be savior. He is ultimately killed by the even more powerful Achilles. To understand Memnon’s role in the saga, it’s worth revisiting the story of Troy and what made Memnon such a captivating figure.

The Trojan War had its beginnings in a beauty contest. What happened is that Paris, the handsome son of the King of Troy, had the honor of judging a beauty contest between three of the most beautiful Greek goddesses: Aphrodite, Athena, and Hera.

Aphrodite, hoping to be declared the winner, promised to provide Paris with the most beautiful woman on earth if he chose her. When he obliges, she brings him to Helen, a stunningly beautiful woman who happens to be the wife of the King of Sparta.

Paris and Helen soon elope together and run off to Troy. Now, if you know anything about the war-like Sparta – or, for that matter, jealousy – you know that the King of Sparta wasn’t too happy about his wife being stolen from him. And he didn’t take any half-measures. Instead of negotiating, he sent an army to conquer Troy and bring his wife back.

What followed was a ten-year siege that became the subject of Homer’s epic poem, The Iliad. Homer’s description of the final year of the war is perhaps the most famous war story in history.

But it’s another work, the Posthomerica, in which the Ethiopian warrior Memnon appears. Just as Troy is losing hope, the Ethiopian king arrives with a vast army of warriors to help liberate the besieged city.

Memnon Comes to the Rescue

In the Posthomerica, written by Quintus Smyrneaus sometime in the 3rd century AD, Memnon reaches Troy just as the city’s leaders are discussing surrendering to the formidable Greeks.

Up to that point, the Trojans suffered terrible losses at the hands of their enemies, particularly Achilles. He had slain both Hector, the king’s oldest son, and Penthesileia, the Amazonian daughter of Ares.

With the death of Penthesileia and her fierce Amazonian maidens, the Trojan King Priam was despondent. As an Amazonian warrior, Penthesileia was one of the only people who could have stood a chance against Achilles. Still, the king held out some hope that Memnon would prevail, even though deep down he realized that it was probably too little, too late.

When Memnon finally arrived, the Trojans received a much-needed boost to their morale. King Priam offered to hold a feast in his honor, but Memnon refused, saying he’d prefer to be well-rested for the next day’s battle. At that, Memnon gets up, excused himself, and goes “to a bed that was his last.”

The next day, the combined army of Trojans and Ethiopians rushed out of Troy’s gates and confronted the Greeks in bloody, close-combat fighting. Memnon slays several important Greek warriors, including Archilochus, the son of Nestor. The killing of Nestor’s son sets off a chain of events that will ultimately result in Memnon’s demise.

Nestor plays a role in several works of Greek mythology, but in The Iliad, he is portrayed as an elderly warrior who offers advice and arbitrates disputes. When he learned that Memnon killed his son, he went to Achilles for help. Achilles, who was a half-god like Memnon, is perhaps the only person who could kill the great Ethiopian warrior.

Achilles is moved by the death of Archilochus and so he and the equally formidable Ajax go out to the battlefield to search for Memnon. They found him near the water, cutting a path through the fleeing Greeks who were heading toward their ships.

The Final Battle

According to the myth, as soon as the pair confront Memnon, Ajax leaves Achilles on his own, sure that Achilles’ skill and strength will win out against the Ethiopian king.

Ajax has good reason to be confident. Though both Memnon and Achilles have parents who are gods, Achilles was dipped in the River Styx (the mythological river of the underworld) when he was a baby. This made him invulnerable wherever the water touched him.

The only part of his body that remained vulnerable were his heels since that was where his mother, the goddess Thetis, held onto him while submerging him in the water.

Later on in the battle, Paris would eventually strike him in the heel with a divinely-guided arrow, killing him. But against Memnon, Achilles’ invulnerability meant that for all the prowess of the great Ethiopian king, Memnon stood little chance against his adversary.

During the duel, the gods watched in fascination as Zeus imbued both men with superhuman size and strength. So fierce was the fight between these two warriors that they paid little heed to the slaughter that was going on around them.

The two giants fought tirelessly, driving their spear points into one another’s shields and drawing blood again and again. The fight might have lasted forever if it weren’t for the Fates, who intervened on behalf of Achilles.

With the mothers of both warriors looking on in fearful anticipation, a bright Fate took Achilles’ side while a dark Fate invaded Memnon’s heart. With the fight all but decided, Achilles finally dealt Memnon a mortal blow by plunging his sword straight through Memnon’s chest.

The Legacy of Memnon

Long before the Posthomerica was written, two monumental statues were built that would later become associated with Memnon in ancient Egypt. These two statues, built outside of Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple, were originally meant to honor the great pharaoh who was buried there.

Centuries later, however, as Greek immigrants and travelers came into the country, they saw a striking resemblance between the statues of Amenhotep III and another great African – Memnon.

Over time, the statues became known to the Greeks as the Colossi of Memnon. Some Egyptians even came to recognize the link. In fact, in the 3rd century BCE, an Egyptian historian called Manetho claimed that Memnon and Amenhotep III were the same person.

According to the Greek historian, Strabo, who lived from 65 BCE to 23 AD, the statues were at some point damaged in an earthquake. Thereafter, they made noises every dawn that resembled singing.

These singing statues attracted tourists and pilgrims from all over who believed that the noise was a divine voice that could answer their questions. While the Colossi of Memnon no longer “sing” since they were repaired by a Roman emperor, they still fascinate tourists from all over the world.

They may not have been built for the greatest Ethiopian warrior who ever lived, but they do bear his name. And as long as people still flock to the statues, his legacy will continue to be remembered.